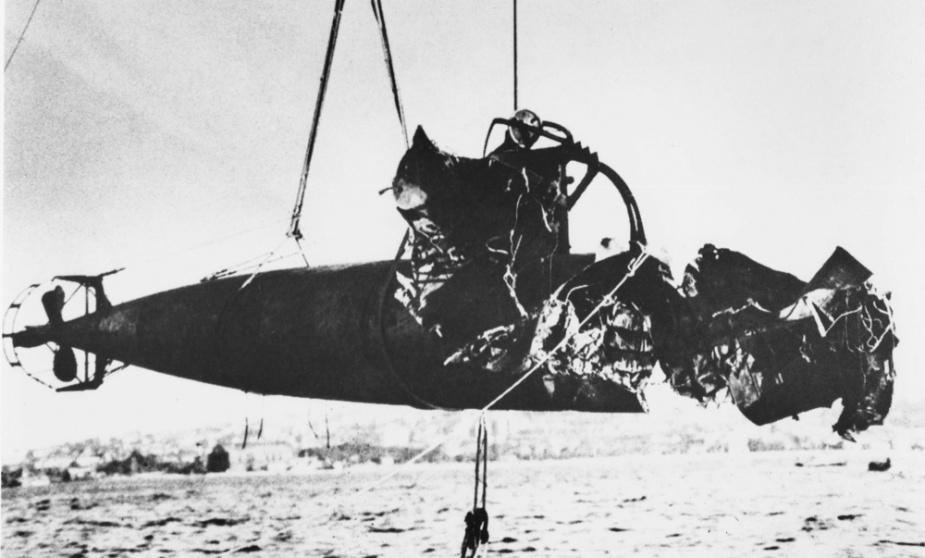

On the night of 31 May 1942, my grandfather was a young boy hiding under the kitchen table as Sydney went into a panic. The Pacific War, a distant thought to many Sydneysiders, had come home. The accommodation ferry HMAS Kuttabul had been torpedoed in Sydney Harbour by a Japanese submarine. And 21 lives—19 Australian and 2 British—had joined the statistics of the mounting war dead. Australia intimately knows the risk that adversary submarines left unchecked can pose.

Fast-forward to 2023, and the Indo-Pacific has been in the midst of a submarine arms race for more than 10 years. In 2019, 75% of the world’s non-US submarines operated in the Indo-Pacific region. That statistic alone makes it clear that the Australian Defence Force requires an effective anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capability.

Long the poor cousin of the spheres of maritime warfare, ASW has entered the general consciousness of Australian defence analysts as an important component of undersea warfare. The AUKUS announcement brought it to the fore with the decision that Australia would acquire nuclear-powered submarines with the assistance of the US and the UK. Nuclear-powered submarines perform a multitude of tasks, including intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; long-range strike; covert insertion of special forces; minelaying; and anti-submarine warfare.

In many ways, submarines are the most versatile maritime platforms in a modern navy’s order of battle. That’s a point not lost on Australia, as it works to avoid a capability gap between the retirement of its ageing Collins-class submarines and the AUKUS nuclear-powered submarines. It’s also not lost on a number of countries in the region. For example, it’s expected that China’s current order of battle of 66 submarines will grow to 76 by 2030.

It is in this context that the defence strategic review states that the immediate investment priorities in the maritime domain include a fleet consisting of ‘Tier 1 and Tier 2 surface combatants in order to provide for increased strike, air defence, presence operations and anti-submarine warfare’. ASW also gets a hit out as a priority in the air domain, with the DSR stating that the air force must be able to maintain ASW as a domain priority.

All of this indicates that the revised ‘focused force’, as directed by the DSR, will include an enhanced ASW capability.

In some ways that has already been borne out, with the news that the Royal Australian Navy will acquire an expeditionary version of the US Navy’s surveillance towed array sensor system (SURTASS- E), a containerised towed array with a passive and low-frequency activity capable of being deployed on a multitude of commercial vessels. Given the speed and vulnerability of commercial vessels, this is a strategic capability that is appropriate to deploy in the vicinity of key chokepoints or known submarine transit lanes such as the Luzon Strait.

However, it is not a tactical capability to be deployed and pre-positioned in the hunt to locate a submarine. It is on this hunt that a system of systems is required to locate and then continue to track a threatening submarine. Such a system of systems will need to be underpinned by an effective theatre ASW concept with a strong backbone of C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance).

So, what is the system of systems required to locate and track a submarine? As every ASW practitioner knows, the best way to combat a submarine is to destroy it while it’s alongside a wharf. However, significant practicalities get in the way of this—not least that, unless it’s during a declared conflict, this is an ardent breach of international law. So, short of striking a submarine alongside the wharf, effective ASW requires the ability to track a submarine from when it dives throughout its transit. This requires an enmeshing of satellite capabilities, strategic towed arrays, seabed arrays, tactical towed arrays, maritime patrol aircraft, ASW helicopters, submarines and information sharing with like-minded partners. That is the system. Of course, connecting these dots requires effective communication and picture compilation. But the key point is that every element of this system is needed.

It is in this light that the DSR’s recommendation that a surface combatant fleet review is needed to ‘ensure its size, structure and composition complement the capabilities provided by the forthcoming conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarines’ raises some concerns. As highlighted in my recent article ‘National defence and the navy’, the assertion that acquiring nuclear-powered submarines warrants a rethink of the surface combatant fleet structure seems tenuous. Nuclear submarines provide the same effects as conventional submarines; they just do it faster and with greater endurance—two elements that are important given Australia’s geographical location.

However, to assume that the existence of nuclear-powered submarines from the 2030s in the RAN’s order of battle changes the foundational structure of the fleet, if in fact that is the assumption, is concerning. A structural review may be needed for many reasons, including the continuing cost blowouts of the Hunter-class frigates, the vulnerability of the lightly armed planned Arafura-class offshore patrol vessels and the RAN’s limited maritime strike capability.

Conventional submarines can have an average dived speed of 16–17 knots on a sprint, more than likely reduced to 10 knots on patrol, give or take a few knots. While the numbers may differ, the point is that employment of conventional submarines in an ASW role requires specific positioning to place them in a position to intercept a threatening submarine. It’s a kind of one-shot thing. Nuclear-powered submarines, with an average dived speed of 30 knots, are not so constrained by a requirement for perfect positioning to be effective.

However, even with the advantage of speed, under the rule of three, even if nuclear-powered submarines are the best submarine hunters, a fleet of eight (once fully acquired in the 2040s) will give the RAN the ability to have two to three operational at any one time—assuming that three will be in refit and two or three will be at various stages of force generation, leaving two or three for operational deployments. Deployments will need to span the full spectrum of submarine taskings.

With over 75% of the world’s non-US submarines operating in our region, the numbers speak for themselves. Even if submarines are the best submarine hunters, the proposition that eight nuclear-powered submarines could meet the ADF’s required tactical ASW capability is a fallacy. We will need much more than that. This is partially mitigated by the Air Force’s fleet of 12 P-8 Poseidon ASW aircraft, but only partially.

Effective ASW is achieved through a system-of-systems approach. And in that system of systems, the RAN requires strategically placed seabed arrays and a tactical towed array system similar to that offered by the Hunter-class frigate (although this isn’t unique to the Hunter). A view that nuclear-powered submarines replace this need denies the maths and the practicalities of the situation. For too long the RAN has been without this capability, and with a luxury of distance has been able to underestimate the ASW threat. That luxury is no longer available.

In considering the fleet structure under the surface combatant fleet review, the ADF must not be captured by the view that nuclear-powered submarines can, by themselves, effectively address the ASW challenges in the region. It must remember that effective ASW requires more than just one exquisite capability. It requires a system of systems underpinned by concepts and C4ISR. In that system of systems, the RAN needs an effective tactical towed array system. Whatever the future of the Hunter class, the surface combatant fleet review must not be blinded by the notion that to deliver an effective ASW capability for the ADF all we need is eight nuclear-powered submarines.