Terrorism-related deaths fell in 2016 according to the Institute for Economics and Peace’s 2017 Global Terrorism Index. It’s the second year in a row that deaths caused by terrorist acts declined. But while the number of deaths has fallen, the spread of attacks has increased. For possibly the first time in history, two out of three countries in the world have experienced a terrorist attack. The spread of terrorism has been partly driven by the increasing reach of radical Islamist extremism, in particular the meteoric rise of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

In 2016, the radical group recorded its deadliest year to date, killing over 9,000 people. Most of those deaths occurred in Iraq. However, since 2014 the group has also been responsible for a dramatic increase in deaths in developed countries. In 2016, ISIL and its offshoots were operating in 28 countries, more than double the number in 2015.

The spread of ISIL’s reach is noteworthy because it defies a broader, more positive trend globally. The Global Terrorism Index shows that the number of deaths from terrorist acts has now fallen by 22% from the peak in 2014. Three of the four deadliest terrorist groups—al-Qaeda, the Taliban and Boko Haram—were collectively responsible for 6,000 fewer deaths in 2016 than in 2015. However, not only did the number of deaths attributed to ISIL and its affiliated groups increase, the group also expanded its reach, including into Southeast Asia.

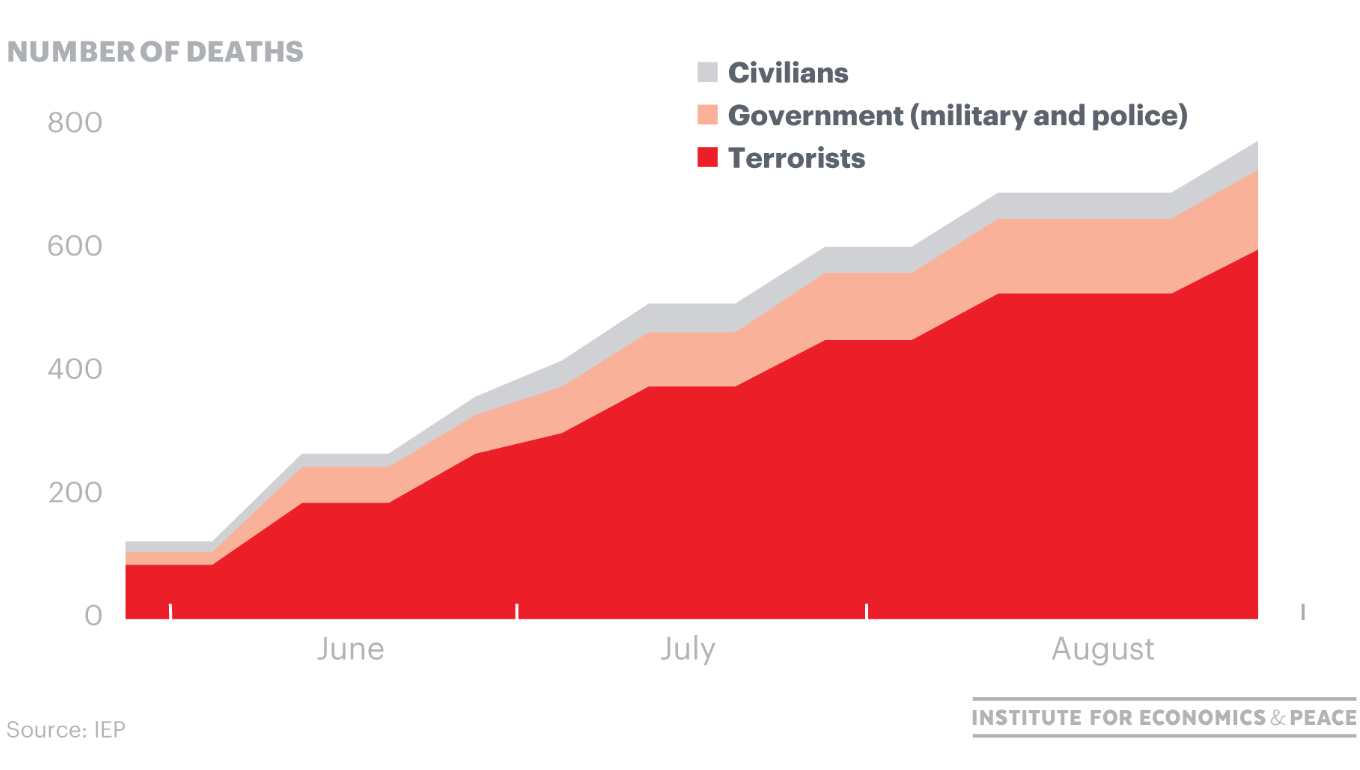

In 2016, a video emerged featuring pledges to ISIL from affiliated militants in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. The video signalled the group’s intention to expand into Southeast Asia and it designated an emir in the Philippines. In May this year, ISIL-affiliated militants captured the Filipino city of Marawi. In the ensuing battles with the militants, 603 Filipino soldiers were killed between 30 May and 29 August (see the graph below). Filipino forces only recaptured the city last month.

Marawi City: ISIL civilian and military deaths, 2017

The territorial gains that ISIL made in Iraq and Syria before its recent military defeat in both countries owed more to the collapse of the state, coupled with ISIL’s military organisation, than to strategic brilliance. However, it showed that from ISIL’s genesis, the group has sought to exploit vulnerable areas to establish territorial dominance. Once it loses territory, as it has in Iraq and Syria, it appears to revert to a more ‘conventional’ insurgency involving terrorist attacks against civilians.

The territorial gains that ISIL made in Iraq and Syria before its recent military defeat in both countries owed more to the collapse of the state, coupled with ISIL’s military organisation, than to strategic brilliance. However, it showed that from ISIL’s genesis, the group has sought to exploit vulnerable areas to establish territorial dominance. Once it loses territory, as it has in Iraq and Syria, it appears to revert to a more ‘conventional’ insurgency involving terrorist attacks against civilians.

The capture of Marawi by ISIL-affiliated militants demonstrates the real potential for other pockets of insurgency to emerge across the region. Like the leftist Soviet-backed groups that spread in the 1960s and 1970s, ISIL has proven successful in aligning local causes with its international agenda. There’s a long history of perceived persecution across Southeast Asia that ISIL could exploit, including campaigns allegedly targeting Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims, Thailand’s Malay Muslims and China’s Uyghur Muslims.

The plight of the Rohingya has been well documented recently. The alleged burning of their villages has forced many to flee to refugee camps in neighbouring Bangladesh. The Myanmar government has been accused of conducting state-sponsored political terrorism. The 2017 Global Terrorism Index highlights the strong link between political terror and terrorism. Counterterrorism scholars have also repeatedly warned that repressive counterterrorism measures could motivate Muslim fighters from ISIL or other groups to aid their Rohingya Muslim brothers.

Similarly, for many decades Malay Muslim groups have been in conflict with the Thai government in the country’s southernmost provinces. The conflict has been fuelled by the predominantly Buddhist government’s assimilation policies, which are perceived as targeting the ethnically and religiously distinct Malay Muslims. The insurgency has recently taken on an increasingly religious dimension that has raised fears that the movement’s calls for independence could be hijacked by non-local Islamist extremists.

In China, nearly 400 people have been killed in 93 terrorist attacks attributed to Uyghur separatists in the past 10 years. According to the Global Terrorism Database, more than 60% of the attacks occurred in Xinjiang. Beijing has long suppressed any calls for independence in the resource-rich province. ISIL has already shown interest in drawing Uyghur ambitions into its global agenda. Early this year, ethnic Uyghurs who had travelled to Syria to join ISIL released a video declaring war with China.

As ISIL’s core diminishes, it’s possible that the group will expand into other regions. Analysis shows that ISIL prioritises politically unstable regions that have porous borders and lack educational and economic opportunities. ISIL has shown that it can make quick gains in such areas, and improve its ability to recruit, by providing resources and expertise. For example, ISIL’s central headquarters in Iraq provided nearly US$600,000 to fund operations in Marawi. Those resources helped militants become more organised and skilled in urban combat tactics. Intercepted messages also show a sophisticated command structure in the region.

Such successes encourage foreign fighters, including those fleeing Iraq and Syria, to travel to other regions where ISIL has greater influence. That idea has already been advocated by ISIL, which released a seven-minute video in August this year asking for fighters to join ISIL in Southeast Asia. In the Philippines, some 20 Indonesian fighters have joined ISIL-affiliated groups in Mindanao.

This analysis highlights the need for Southeast Asia nations and the global community to develop long-term strategies for dealing with the spread of terrorism. That includes focusing on reducing political terror and counterterrorism measures that may inadvertently increase the risk of terrorism. This imperative is all the more pressing given the spread of terrorism across the world and the internationalisation of ongoing conflicts through ISIL.