Scenes of Australian police, mostly Victorian, using physical force to deal with non-compliant citizens protesting against Covid-19 restrictions have become news fixtures. Breakfast television commentary swings between criticising police use of force and targeting the confrontational approach of members of the public armed with mobile phones and attitude.

Covid-19 lockdown protesters’ acts of defiance must be increasing the risk of spreading the disease, but the more worrying and longer term outcome could be their corrosive impact on Australians’ trust in their police. A loss of public trust in police will affect their social licence to operate in our communities. This loss of trust will have a direct impact on police services’ operational performance—with damaging flow-on consequences for social cohesion.

Covid-19 is fundamentally a health problem, and the average Australian police officer would prefer not to be undertaking lockdown-related duties. Given the high level of public trust in police, and their existing capabilities, there’s little wonder that our governments looked to them to implement and enforce our Covid-19 rules. The virus is so infectious that governments had little choice but to implement lockdowns and they brought with them an unprecedented demand for police services.

In response to the broader Covid-19 challenge, the federal, state and territory governments have provided police with extraordinary powers. Aware of the possible impact on their public image, police services would have been concerned about their roles during the pandemic. However, I suspect that governments did not consider the long-term impacts of their measures on policing, and police forces probably had little choice but to accept their counter-Covid responsibilities.

The images of police, adorned in riot gear, with batons and shields at the ready, walking in formation through Melbourne’s iconic Queen Victoria Market during Sunday’s anti-lockdown protest illustrate this point. The officers were responding to the actions of as many as 250 protesters who, under current legislation, were committing offences. They arrested 74 and issued 176 fines.

Any blame for the disruption and health risks associated with this event rests solely with the protesters. Nonetheless, the images of the response will have eroded public trust in the police as being able to calmly solve problems in the community.

Similarly, video of a terrified young woman being forcibly removed from a car at a Victorian checkpoint for allegedly failing to provide information and refusing to follow a police officer’s direction will do little to promote trust from a Covid-19-weary Australian public.

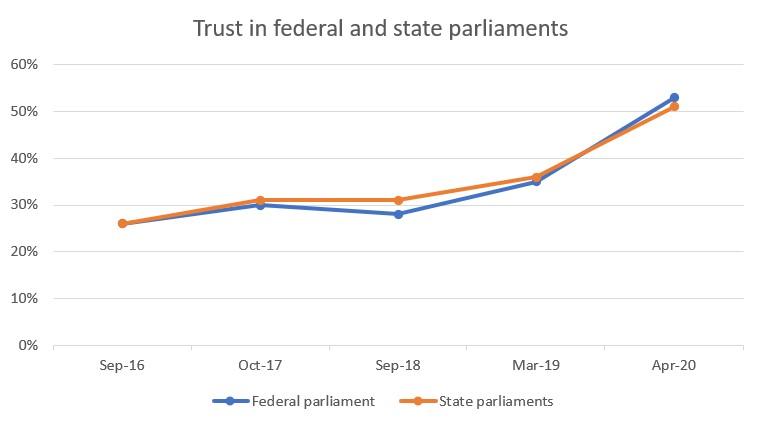

Public trust is more brittle and perishable than ever. You only need to look at longitudinal studies of public confidence in Australia to see this at play. During the 2019 federal election, trust in government reached its lowest level since the constitutional challenges of the 1970s.

Trust in institutions like the federal and state parliaments was, until Covid-19, also perilously low. By April this year, though, trust in these institutions had rapidly improved on the tails of Australian governments’ successful responses to Covid-19. The longer Covid-19 restrictions remain in place, however, the more likely there is to be a significant reduction in public trust in policing.

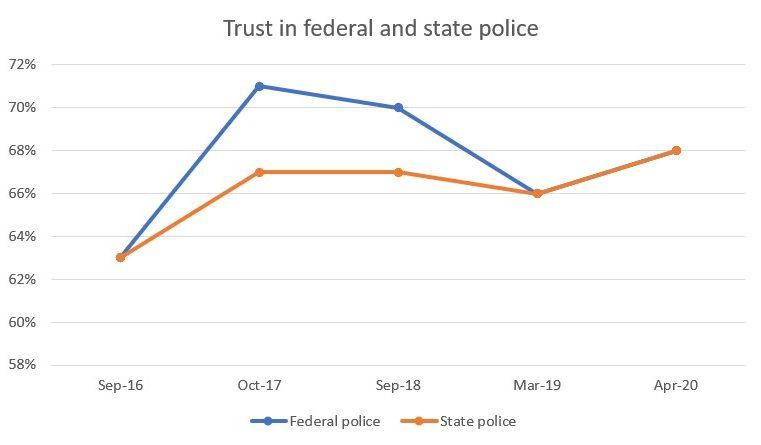

In contrast with our political institutions, federal and state police have been Australia’s most trusted institutions for many years.

The trust earned by Australian police forces over decades has provided their social licence to operate within our communities. It allows police to exercise discretion—the power of the constable—in their duties. It has supported their right to use force in response to particular circumstances. It has generated the kind of goodwill that allows communities to work with police to solve problems.

An unexpected consequence of Covid-19 could well be a loss of law enforcement’s social licence. And this loss will have tangible impacts on police performance.

State, territory and federal governments need to act now to ensure that our police do not become the focus of the frustration of Covid-19-weary Australians. A good starting point would be public information programs explaining that police enforce the rules, but they don’t write them.

Australians need to be provided with mechanisms to express their concerns lawfully. While this will not be to the satisfaction of all, it would offer people a chance to be listened to.

Throughout Australia’s struggle with terrorism since 2001, social cohesion has been key to success. Governments need to consider developing a social-cohesion initiative dealing directly with the divisive impacts of increased economic inequality as well as the compromises made in responding to Covid-19.

Australia’s police services need to consider their recovery plan for policing after Covid-19. This plan needs to include retraining of officers who have performed Covid-19 duties. Careful consideration needs to be given to ensuring that police access to extraordinary powers during the pandemic is rapidly rolled back when it is no longer justified.