Facebook diplomacy, click farms and finding ‘friends’ in strange places

Posted By Damien Spry on September 7, 2017 @ 06:00

Diplomatic missions routinely use social media, especially Facebook, as a platform for public diplomacy and consular support. Their main target audiences are local people.

Among the 22 Facebook pages managed by Australian diplomatic missions (embassies, consulates and high commissions) for which I have analysed the 2016 data, two at least appear to have large numbers of page likes from unusual locations.

The Australian Embassy in Germany page had about a third of its 19,000 followers from the Philippines and Bangladesh (and only 13% based in Germany). The Australian High Commission in New Zealand is even more perplexing: 70% of its 26,000 followers are in Cambodia; only 3% are in New Zealand. In fact, rather strangely, its Facebook page has succeeded in attracting more Cambodian followers than the Facebook page of our actual embassy in Cambodia [1].

Australian missions are not the only ones with some curious figures. New Zealand, Canada and the US all have some similarly unlikely fan bases in places like Bangladesh, India and Pakistan for pages based in and targeting the UK, US and New Zealand. The US Facebook page in New Zealand is followed by more Filipinos, Americans, Indians and Bangladeshis than New Zealanders, who make up a mere 7% of the 55,000 page followers.

In some cases, it is entirely kosher to have page followers from a variety of locations. For instance, it makes sense when there are large numbers of expats (Filipinos in Hong Kong) or a significant diasporic or political connection (Israel in the US), or when an embassy covers several countries. While they aren’t the target audience, they are legitimate followers and there’s no reason why they shouldn’t be welcome. But that still doesn’t explain why 18,000 Cambodians have taken such a liking to our high commission in Wellington.

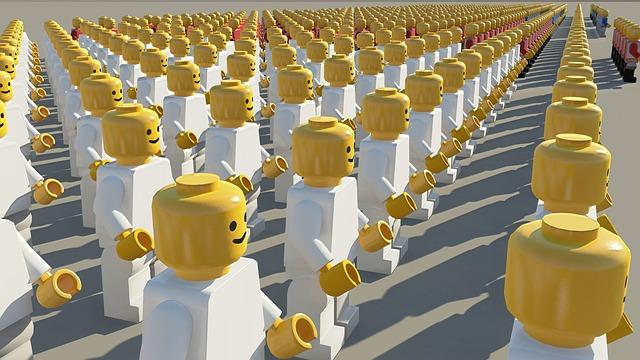

The oddly located followers could also be the product of click farms [2]—modern-day sweat shops stacked with networks of mobile phones and computers [3] offering pages likes, clicks and other digital engagement for a fee. They are often based in South and Southeast Asia where low-paid, technologically literate labour is available.

Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, for its part, has expressly stated that it doesn’t pay for followers, but it hasn’t explained the strange results in Germany and New Zealand. Diplomatic missions do pay to boost posts, which can be a useful (and cheap) way to promote important information. Australia’s Hong Kong consulate, for example, paid to boost posts about the consular arrangements for voting in the 2016 Australian federal election, targeting expat voters. Those posts were among the most popular for the year and a useful way to ensure participation in the election.

It’s possible that a third party was responsible for stacking pages with false likes. PR agencies may be tempted to do that to show results for social media campaigns. And it’s possible that, in locations like the UK, numbers may reflect locals who are from, for example, Bangladesh but live in the UK and are interested in migrating to, say, New Zealand. (That’s the explanation I was given by New Zealand officials in London.)

It’s also possible that these cases are a legacy from earlier days of social media, before DFAT’s policy caught up with practice. And it wouldn’t be the only one. We know that the US paid to boost its social media audience: a 2013 report by the US State Department’s Office for the Inspector General [4] outlined how the US had spent about $630,000 on two campaigns to increase its followers from about 100,000 to over 2 million.

That practice has rightly ceased. Sourcing page followers from click farms to boost page metrics is wasteful and counterproductive. The worst aspect of it is how it both reflects and reinforces the deeply flawed metrics-led approach to evaluation. It’s easy enough to imagine succumbing to the pressure to demonstrate success by pointing to large numbers. Numbers can at times be useful for analysis and review, but the overemphasis on metrics as measures of achievement can encourage actions that undermine performance.

Amassing fake followers simply doesn’t work as a promotional tool, and almost certainly makes things worse. It’s hard enough to reach the intended audience [5] (a post might be read by 2–6% of followers—estimates vary—unless it’s supported through a paid promotion). So, if the bulk of the page followers, likes or video views aren’t legit, then posts are even less likely to be seen by those for whom they’re intended. Every time a post is ignored (which fake followers will do), the Facebook algorithm de-prioritises it in the newsfeed, making it even less likely that it will be seen.

There are other problems. It’s also a waste of money. (Though not much. Facebook page likes are ridiculously cheap: around $1 for 1,000 likes.) And it’s deceptive; a kind of false advertising that seeks to demonstrate significance and enhance reputation but does the opposite.

Ultimately, ranking pages or evaluating online post performance by using page likes should be avoided. Pressure to increase metrics risks leading public diplomacy personnel away from the basics of good communications practice: solid, timely and compelling content, targeted at relevant audiences and with a specific goal in mind.

There are many ways diplomats can better use Facebook to connect with international audiences. Using click farms isn’t one of them.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /facebook-diplomacy-click-farms-finding-friends-strange-places/

URLs in this post:

[1] Facebook page of our actual embassy in Cambodia: https://www.facebook.com/AustralianEmbassyPhnomPenh/

[2] click farms: http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2017/06/14/explainer-click-farms-inside-online-phenomenon

[3] stacked with networks of mobile phones and computers: https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/43yqdd/look-at-this-massive-click-fraud-farm-that-was-just-busted-in-thailand

[4] 2013 report by the US State Department’s Office for the Inspector General: https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/723785/state-department-facebook-likes-ig-report.pdf

[5] hard enough to reach the intended audience: http://www.socialmediatoday.com/social-business/new-study-finds-facebook-page-reach-has-declined-20-2017

Click here to print.