Were fascism to ascend again in Europe, international security would be menaced and the liberal international order be even more imperilled. However, Europe’s current far-right parties fail to meet the minimum fascist criteria.

Just as the taxonomy of European far-right parties is not settled, there is no unanimously agreed definition of 1930s fascism. Differences over generic fascism or a recognisable fascist ideology punctuate the scholarly literature.

Even the two fascist exemplars, Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany, had important differences as well as similarities. However, the fascist movements that arose after 1918 and their shallow imitators—like Franco’s Spain and the Romanian Iron Guard—can be distinguished from today’s far-right movements.

Prominent writings on fascism point to political religion, the myth of regeneration, and the idea of the ‘new man’. In their historical setting these concepts merged and produced the violent revolutionary interwar fascist alternative to liberalism, socialism and conservatism.

Scholars detect in fascism a secular political religion. Mussolini’s The doctrine of fascism (1932) is suffused with a sense of transcendent spirituality and the sacredness of the fascist political mission. Mussolini believed that by subordinating the individual to the nation and its generations, fascism leads to ‘a life free from the limitations of time and space, in which the individual, by self-sacrifice, the renunciation of self-interest, by death itself, can achieve that purely spiritual existence in which his value as a man consists’.

Mussolini ‘sought the revolutionary and ultimate objective of commencing time anew, with the intent of creating a novel type of civilisation and human being based on the collectivity and the state’. He believed that, ‘From beneath the ruins of liberal, socialist, and democratic doctrines, fascism extracts those elements which are still vital.’

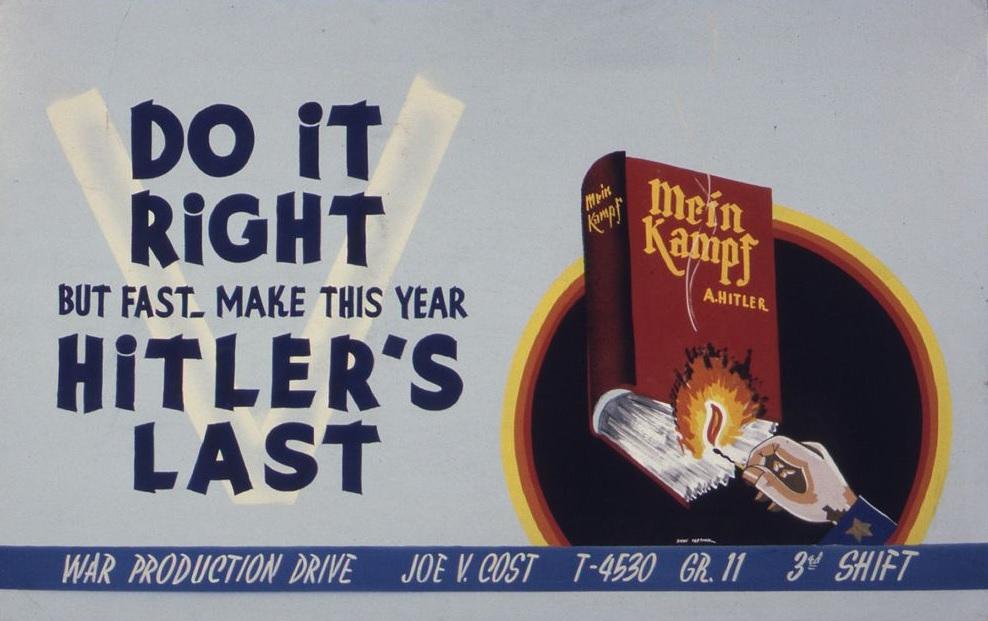

The myth of the 20th century (1930) by Alfred Rosenberg, the chief ideologist of the National Socialists, was as influential in Nazi thought as Mein Kampf. His misogynist, anti-Semitic and distorted work on the metaphysical superiority of Nordic blood proclaims that the fascist mission is ‘to create a new human type out of a new view of life’. To succeed, Hitler’s 1933 revolution must aspire to the ‘highest value, around which all remaining commandment of life must be grouped, [and which] must correspond to the innermost essence of the people’.

Roger Griffin describes fascism ‘as a revolutionary form of ultra-nationalism that attempts to realize the myth of the regenerated nation’. And it is a myth that, ‘applied in practice[,] creates a totalitarian movement or regime engaged in combating cultural, ethnic and even biological (“dysgenic”) decadence and engineering a new sort of “man” in an alternative socio-political and cultural modernity to liberal capitalism’. Central to fascism’s allure in the 20th century was the promise of ‘comprehensive renewal (“palingenesis”)’ and a longing for ‘a new (political) religion, a cause worthy of sacrifice’.

As morally distorted, murderous and calamitous as the fascist era was, it was a movement initially grounded in a spiritual and transformative metaphysics that informed a political, social and aesthetic revolution. The populist, xenophobic, anti-immigration, Islamophobic, white supremacist and Eurosceptic political parties and groups scattered across the European Union today might adopt some of the superficial paraphernalia and symbolism of the fascist past but lack the missionary fanaticism that united fascists.

Today’s right-wing groups are dangerous and passionate about their issues. Some advocate political violence. But what passes for their ideology was described recently as ‘rather vague and inconcrete’ and as a mixture of ‘political isolationism, protectionism, racism, white nationalism, anti-Semitism and populism’.

Perhaps immigration is the loose connecting tissue between the far-right parties’ supporters. Research also points to a split between support for extremists associated with ‘economic insecurity’ and a ‘cultural backlash’ with populists voters. Others point to the consequences of the time of shedding and cold rocks and subsequent rising unemployment.

The ideology of Europe’s current far right lack’s the depth and breadth of the interwar fascists. The genuine fascists were responding to the widespread sense that democracy was responsible for all that was wrong with Western Europe after the First World War. Democracy, they believed, had ‘exacerbated class tensions, cowardice, selfishness, materialism, and, above all, “decadence”’.

Good policy begins with understanding the issue irrespective of one’s objectives towards it. Mistaken or unjustified beliefs can lead to over- or underestimating the risks and perverse outcomes. In Europe, liberal and centrist politicians and media are still perplexed by the emergence of far-right political parties and are unsure how best to respond.

In reporting on the recent Chemnitz protests in Germany, the Swedish election, Russian politics and the Ukrainian far right, the terms nationalist, fascist and neo-Nazi are interchangeable. However, fascism is more than giving Nazi salutes, dressing up and protesting against Islamic or African migrants—even when accompanied by violence. Griffin has observed that ‘the term “fascism” continues to be bandied about by those clearly more interested in its seemingly inexhaustible polemical force than in anything resembling historical or political fact’.

It is hard to conceive that there was any alternative to the terrible war that eliminated the threat of early 20th century fascism. The fascist regimes were implacably hostile and fanatically antagonistic towards the very existence of liberal democracies. But the contemporary right creates a domestic political and policy issue, not an international or a strategic one; and not one requiring the application of military force.

Reforming political and government institutions, strengthening democratic accountability, introducing new policies that address inequalities in wealth, improving access to justice and services, and paying serious attention to minority rights will suffice to cut the ground from under support for the far right.

Of course, these remedies would not suffice in the face of genuine fascism.