We read Graeme Dunk’s recent post on Defence’s love affair with the US Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program with interest. In one sense Graeme is right—as we’ve noted previously, there have been some (slightly mysterious) big dollar figure approvals lately. But we’re not at all sure that Dunk’s conclusion, that it’s at the expense of Australian industry in absolute terms, is right. We also think that FMS will continue to be a major part of delivering capability to the ADF in the future—and that to do otherwise would result in poor capability outcomes.

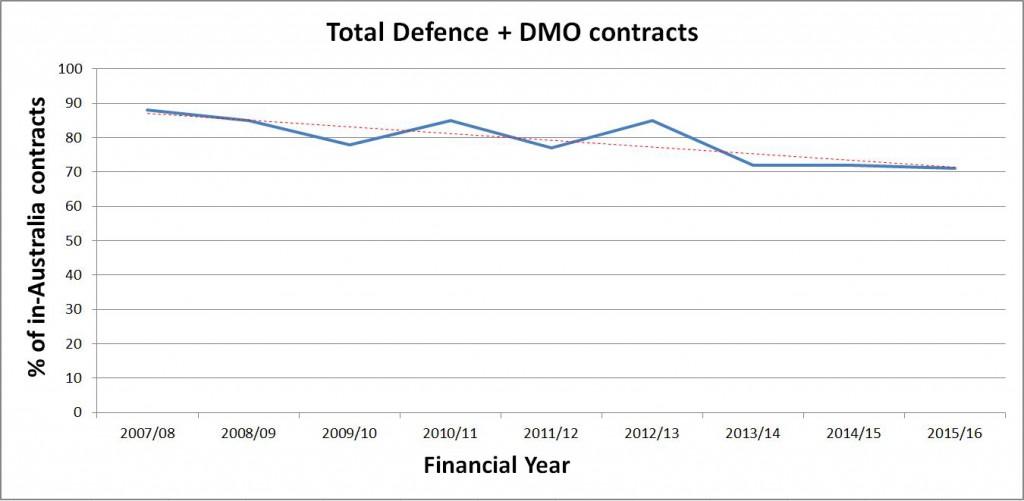

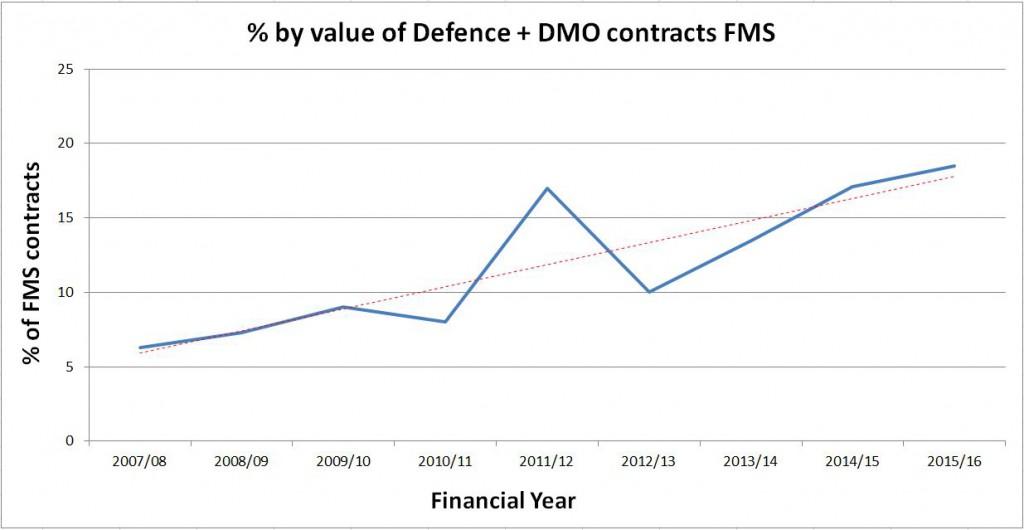

Dunk is right to claim that the proportion of contracts awarded to Australian companies has been decreasing while overall spending has been increasing. But it doesn’t follow that there’s been a ‘steady reduction in the amount of money’ being spent with Australian companies. To see why, look at figures 1 and 2 from Dunk’s piece. Figure 1 shows the trend in the proportion of contracts awarded by Defence and DMO to Australian industry. Figure 2 shows where it went, with FMS contracts increasing as a proportion of total spending.

Figure 1

Figure 2

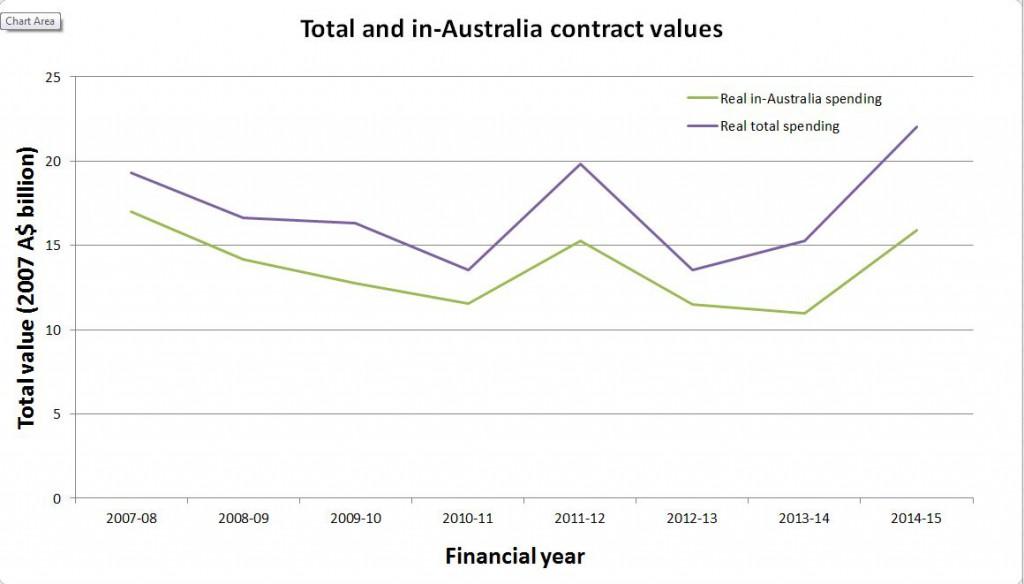

So far so good. But that doesn’t mean that defence spending in Australia is necessarily declining. In fact, because overall spending has increased over the past couple of years, even a slight decline in the proportion of local defence spending has seen the amount spent in Australia increase.

To see why, take a look at figure 3 below. The upper line shows the value of all contracts awarded by year (source: ASPI’s Cost of Defence 2016–17). The lower line represents the total value of domestic contracts, obtained by multiplying the percentage of Australian contracts by the total. We’ve allowed for inflation in this chart, so the figures represent real dollars, and we see that the total value of contracts to Australian companies increases or decreases with total defence industry spending. The amount of money being spent in Australia is just as dependent on total expenditure as it is on the proportion of contracts awarded to Australian companies. The period since 2007 hasn’t been a boom time for Australian defence industry—but it’s a long way from having been a bust.

Figure 3

And, importantly, boom times in defence spending are coming. As Mark Thomson points out in his budget brief, there’ll likely be more dollars available than Defence can spend. The total defence budget for 2016–17 is $32.4 billion. In ten years’ time it’ll be $43.3 billion (in 2016 dollars). Even if the proportion awarded locally declined from 70% to an unlikely 50%, the value of in-Australia contracts would still increase over the decade.

And call us old-fashioned, but we’re also concerned about the ADF getting the capability it needs. The history of Australian defence projects doesn’t fill us with confidence in terms of being able to spend the increased defence budget fast enough to meet requirement needs (or in terms more attuned to Canberra manoeuvring, to avoid underspends). It’s a fact of life that the more ‘Australianised’ a project is, the slower the delivery tends to be. As a nation, we’re already taking a big punt on shipbuilding, with three large projects starting pretty much simultaneously. Then there’s the local build of the Land 400 vehicles. That’s a lot of new work, so the capacity of the defence industry sector might be tested. Local industry might say that planning uncertainty has held back the investment it needs to be a reliable supplier. But the alternative is for the government to either stand up a monopoly supplier (as the UK government has with shipbuilding), or to bankroll multiple competitors for any given capability sector. There are inherent inefficiencies in either approach, so we should hasten slowly, with an eye to building a sustainable and efficient long-term local industry.

Finally, we have to accept that there’s a global trend towards consolidation of defence industry, with fewer and fewer countries being able to develop top-end capabilities on their own. That’s why Australian defence industry already looks like the local outpost of multinational firms. FMS is popular for a number of reasons. First, things arrive on time and at the quoted price (or often a little lower due to the increased economy of scale provided by foreign sales)—and they work. Second, it’s a quick path to interoperability with our major ally. Third, it allows us to exploit the investments that other countries make in product development and production capacity while outsourcing the associated risks back to them.

In short, we see FMS continuing to be a significant, and possibly growing, part of our defence acquisition strategy. But the growth path for the defence budget means that spending on Australian industry can also be on an upward trajectory.