Earlier posts (here, here and here) have looked at force structure from an Australian perspective, but in reality the American alliance dominates all our defence discussions. So our thinking about future force structure alternatives and how they relate to the alliance should start with a basic question: what we want from the alliance?

In defence terms, and from an Australian perspective, the alliance’s function is to gain American support in those instances where America doesn’t consider it in its national interest to be involved. To give some examples, American assistance to Australia during World War II both pre-dated the alliance and was in America’s own interest. But American support for Australia (and the Netherlands) when differences arose with Indonesia over the future of Dutch West Papua wasn’t seen the same way. Similarly, Australia’s 1999 intervention in East Timor didn’t engage America’s national interests and so US support was less comprehensive than some hoped.

So how can the ADF’s force structure be shaped to help gain American support in such circumstances? The most often proffered way is to be a part of America’s wars in the hope of reciprocation; a ‘you owe me one’ strategy. This approach suggests a force structure that can readily be added to a much larger US joint force. Such an additive force structure is easily developed—simply buy a range of off-the-shelf US hardware although, with the operational theatre of future American wars uncertain, the ADF would need to trained for a variety of possibilities. There are several downsides with this approach, including limiting Australia’s ability to undertake independent operations, acquiring capabilities that might be less relevant to our nearer region and doubts whether Australia’s contribution to a much larger American force can be sufficiently significant to ‘buy’ us the required kudos.

In political terms such an approach means potentially signing us up in advance for any and all future American wars; this is a big ask and in many ways makes us the 51st state of the Union! Moreover, American administrations come and go—even if we participate in the current administration’s wars, that may not ‘buy’ us much in support from succeeding administrations. We fought in Korea but the US prevaricated over helping us with Dutch West Papua; we fought in Vietnam and Desert Storm but support for us in East Timor was problematic.

A more subtle approach is to be sufficiently influential as to push American decision-making towards helping Australia in those situations when America is not engaged. If we are sufficiently useful, this could overcome narrow, issue-focused concerns. Developing our force structure in a way important to the US could perhaps help tilt the balance our way.

Given the ADF’s limited numbers, and the prodigious resources of the US, simply being an addition may not gain us, or the Americans, much. The UK used to believe that it needed to provide about 10% of the forces in theatre to have any meaningful influence on the Americans. We couldn’t provide such a large force, so we’d have to seek influence in some specific highly valued niche areas—quality might gain us more than quantity.

A recent study by the well-regarded Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments identified four vital capability areas in America’s current strategic circumstances: special operations forces, cyberspace capabilities, next generation long-range penetrating air surveillance/strike systems, and survivable undersea warfare systems. These ‘crown jewels’ are considered essential even at the expense of other force structure elements, such as conventional ground forces, short-range fighters and surface warfare ships. Australia providing the alliance with more such ‘crown jewels’ might be of real value.

A related approach is by specialising in certain force structure areas while leaving the rest to others. An example is that of the US Marine Corps—an organisation sometimes touted as a model for the ADF—and which is, for historical reasons, optimised for beach assaults on defended shores. For 8.2% of the American defence budget, the Corps provides the US with ‘…31% of its ground forces, 12% of its fighter attack aircraft, and 19% of its attack helicopters’. This high ‘bang for the buck’ ratio suggests the economies of scale the Corps gains by leveraging off the force structure others pay for, including the surface warships, naval tankers, amphibious ships, air support, and the intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance systems the Corps requires for its across-the-beach task.

A similar ruthless role specialisation emphasising a particular capability area could allow the ADF to contribute usefully sized tactical forces to an American combined force. The quid pro quo of course would have to be that the US would provide those capabilities that Australia no longer has. This might sound unpalatable, but such an arrangement already underpins the extended nuclear deterrence shield America provides which allows Australia to focus on maintaining conventional forces. A recent proposal would extend this notion, with the US also providing conventional forces to help in the defence of Australia, allowing us to focus on developing larger land forces suitable for stability and peacekeeping interventions.

Another quality based alternative is for Australia to acquire a force structure that complements America’s, such as maintaining a capability to undertake counterinsurgency operations as the US winds theirs back, jungle warfare, shallow warm-water undersea warfare or mine countermeasures. These are areas that the US Services for various reasons tend to overlook but which historically have been occasionally important. Keeping such capabilities ‘just-in-case’ might of course prove pointless in the actual wars that America becomes involved in.

This is a complex area in terms of considering tradeoffs and of course the future force structure doesn’t have to bear the burden alone of gaining American support in circumstances where they might otherwise opt to sit out. Providing basing policy for example can be beneficial as well. Nevertheless, the design of force structure could be purposefully shaped in such a way as to support the overall objective of making more likely future American support.

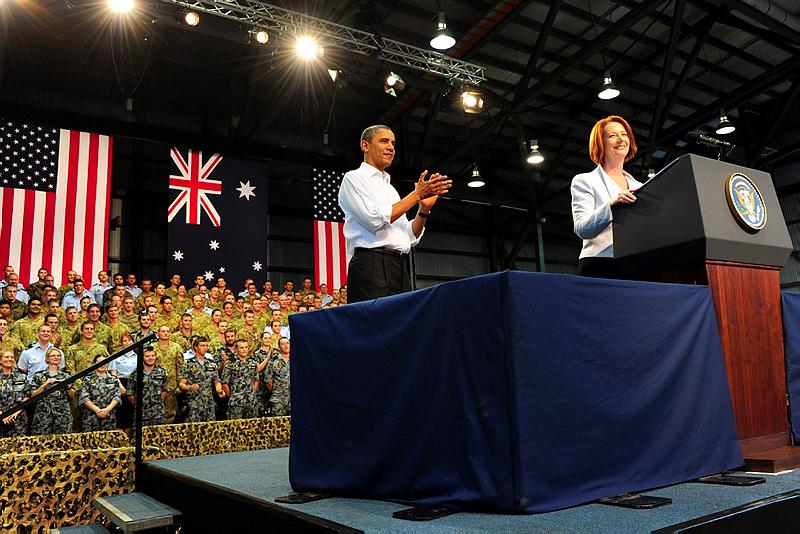

Peter Layton is undertaking a research PhD in grand strategy at UNSW. Image courtesy of Department of Defence.