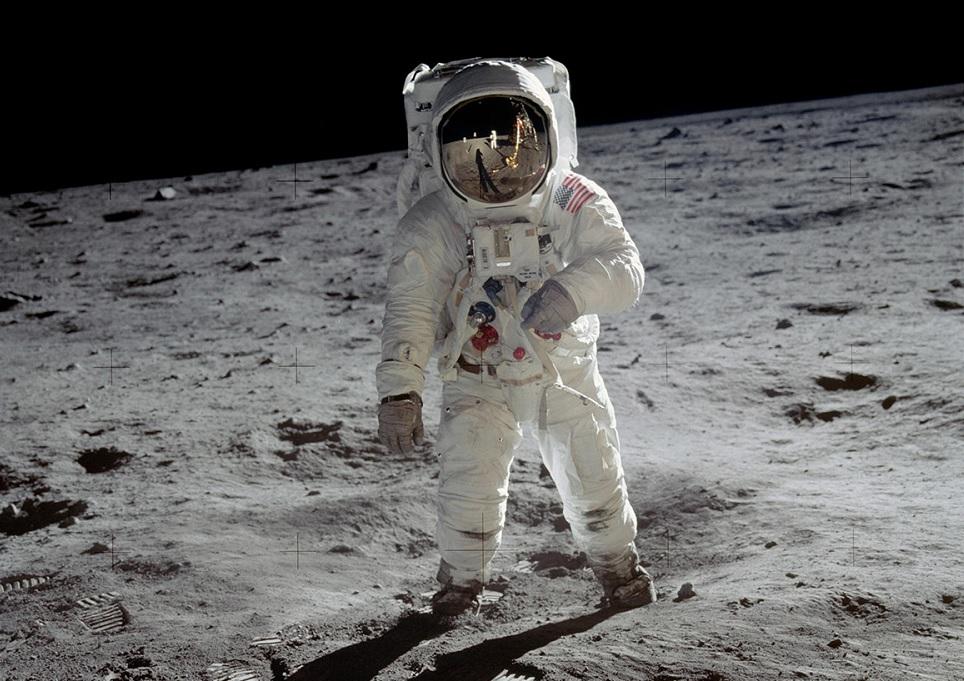

Saturday 20 July 2019 marks 50 years since the landing of Apollo 11 on the Sea of Tranquility and that historic moment when Neil Armstrong took ‘one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind’.

But the excitement was short-lived. Interest in the moon waned as landings became more common and samples of lunar soil multiplied. Indeed, later this year—19 December, to be precise—the world will be able to celebrate the 47th anniversary of the last moon landing, by Apollo 17. Since then, no humans have set foot on the moon. The lack of progress, and associated attrition of skill sets, has been a source of frustration for many in the space community, and criticism has mounted over NASA’s inability to offer a credible and cost-effective strategy to build on the achievements of the Apollo program.

Now the human journey is about to begin again, with a recent commitment by the Trump administration to return to the moon by 2024 under Project Artemis. Rather than just flags and footprints, the new landings on the lunar surface will also establish a small lunar-orbit space station called the ‘Lunar Gateway’ to support future missions, which in turn will support an eventual human landing on Mars in the late 2030s. There’s recognition within the space community that the moon is not only a logical stepping-stone to Mars, but also a base from which to build and sustain a space-based economy that would fund more ambitious goals in coming decades. Getting back to the moon will make it easier to develop the necessary capabilities and skills to enable humans to set foot on the red planet in the 2030s.

The plan for Artemis bears a striking resemblance to the concept on which Apollo succeeded, though clearly the technology has moved on. NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS)—the ‘big booster’ that will launch the Orion spacecraft to get astronauts back to the moon—mirrors the 1960s Saturn V booster in capability. Orion is a slightly bigger and much more advanced vehicle than the Apollo ‘command and service module’.

Unlike in 1969, in 2019 there’s no formally declared space race. President Donald Trump’s space policy directive of 11 December 2017 commits the US to return to human space exploration beyond earth orbit. The Trump administration has since accelerated the original timetable of a return to the moon in 2028 to a landing by 2024, and is seeking this time to have a woman set foot on the moon.

The decision to accelerate the return aligns with Trump’s domestic political agenda and was pitched in the context of growing Chinese space activities. As I’ve noted previously, Beijing has serious plans for ‘taikonauts’ on the lunar surface by the 2030s. It’s conceivable that delays in the US program could encourage China to accelerate its own timetable for testing its Long March 9 heavy booster. That would give it a chance at winning the international prestige that would come with beating the US back to the moon. Then a new race would be on. NASA would be forced to respond under pressure both from the White House and from an ambitious Chinese space program.

The real race now, however, may be between NASA and commercial space players such as SpaceX and Blue Origin, which have ambitious plans for lunar missions of their own. For example, SpaceX’s proposed ‘Starship/Super Heavy’ booster and spacecraft will be fully reusable, and may fly around the moon by 2023.

It’s the innovative approach of commercial space operators that contrasts so sharply with NASA’s reliance on Apollo-era thinking. SpaceX and Blue Origin are emphasising full or partial launcher reusability, which reduces launch costs dramatically compared with the fully expendable NASA SLS. (SLS is estimated to cost US$1 billion per launch and may launch only once a year from 2021.)

By using on-orbit refueling, SpaceX’s Super Heavy can deliver 100 tons to the lunar surface, compared with just 45 tons for the NASA SLS in its most powerful variant, the Block 2 cargo, which may fly by the late 2020s. Rather than a race to the moon, it’s a race to innovate, and the private sector is clearly winning that one.

The space environment is also much more competitive now than it was in 1969. Other space powers—India, Japan and Europe—are all eyeing the moon and the potential resource wealth it offers. Like China, they have a second-mover advantage on the US. Over successive administrations, the US has lacked a coherent space policy, constantly shifting between ‘Mars first’ and ‘moon first’ policies.

Meanwhile, massive cost-overruns and delays on SLS have contributed to a sense that the US is adrift in space—a far cry from the decisive, goal-driven days of the early 1960s, when President John F. Kennedy said:

[W]e choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

Much like in the 1960s, however, plans for a return to the moon are being made in the context of increasing military competition in space, which is diverting resources from human space exploration. But it’s a far more complex environment. China and Russia are developing counterspace capabilities designed to deny the US, and its allies, access to essential space systems. The US and others are responding with new approaches to ensuring space access—for example, the US is considering the potential for establishing a space force early in the next decade.

Getting back to the moon is not just a question of money. But a more complex and contested space environment increases the funding risk for Artemis. NASA is receiving far less funding now than during the Apollo era. The Apollo program cost US$25 billion between 1961 and 1973 (US$153 billion in 2018 dollars). NASA’s entire budget allocation in 2018 was only US$20.7 billion, which has to support other projects besides human space exploration, including ongoing and new unmanned missions; aeronautical research; work in earth sciences such as climate change research and education; and administrative costs.

In the 1960s, Apollo had money thrown at it. In the 2020s, Artemis is attempting to match that goal, and do more, on a comparative shoestring. If the US is to have a hope of achieving and sustaining the goals of Artemis, increased funding for NASA will be essential, or they must bite the bullet and hitch a ride on commercial rockets to the moon.