It’s 1988 and Australia has only a handful of women ambassadors, with just four women serving as heads of mission.

Making a program on the emerging feminine side of Oz diplomacy 33 years ago, 60 Minutes is interviewing one of those women, Sue Boyd, Australia’s high commissioner to Bangladesh.

Question: Is there anything a male ambassador can do that a woman ambassador can’t?

Sue Boyd: ‘Yes—pee standing up.’

Classic Boyd—sharp and smart, doing the business with joyous brio, finding the humour in the deeply serious life of diplomacy.

Boyd knows that international affairs may be about nations, but it’s done by people. Humour is a sauce of diplomacy. Jokes and jests help edge across the chasms of démarche and ease through dragging dialogue.

As Australia’s ambassador to Vietnam, Boyd gave some advice to Vietnam’s foreign minister on joining the Association of Southeast Asian Nations: ‘I told him that Australia could help him in a number of ways to prepare for the coming ASEAN debut. There were four informal requisites for success in ASEAN: playing golf, speaking English, wearing coloured shirts and singing karaoke. We could assist with the first two.’

My memory of this anecdote is that jokes were the optional fifth requisite, but Vietnam’s Communist Party struggled with the dialectics of setting the humour policy.

On giving a speech, another staple of the trade, Boyd adjusted her method as an ambassador in the South Pacific, where strong oral traditions call for an entertaining oration: ‘A storytelling style is the Pacific way. So a short speech will generally not do.’ Thus, on a trip to Tuvulu, Boyd confides to the audience the reason she’s not married:

I was single, because I found that men were like parking meters, either occupied or defective. This went down very well and caused some amusement. Funafuti had just two roads, few cars and certainly no parking meters. I was told later that for the next few days the men of Tuvalu had gone around asking each other, ‘Are you a parking meter?’

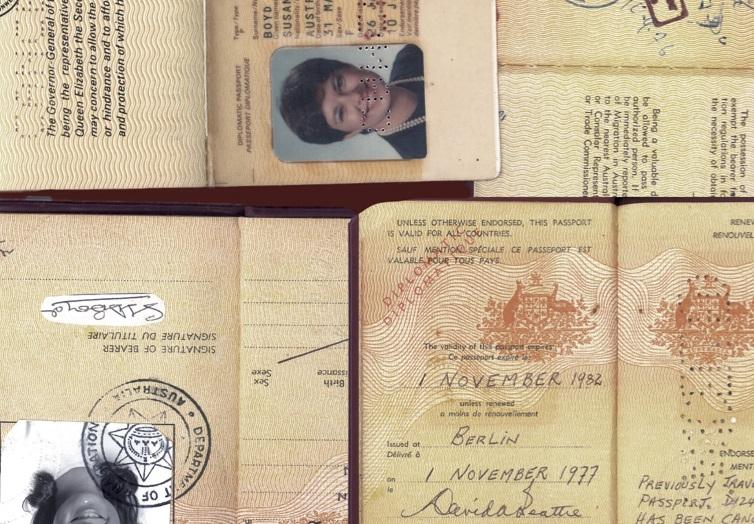

Welcome to Sue Boyd’s life in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade: 23 years in seven missions abroad, plus 11 years in Australia, laid out in her wonderful memoir, Not always diplomatic: an Australian woman’s journey through international affairs. This is ‘a view from the engine room of the making of Australian foreign policy,’ as Kim Beazley notes in his foreword (one of Boyd’s early wins was defeating Beazley in an election for president of the University of Western Australia students’ guild).

Boyd launches the story with Gough Whitlam’s ‘injunction’. Just back in Canberra from her first posting, to Portugal, she was summoned to the prime minister’s office in April 1974 to brief on the Portuguese ‘carnation revolution’. Whitlam boomed three questions at the young diplomat: What’s going on? What does it mean for Australia? What should we do about it? The three points of the injunction, she writes, ‘form the basis of the work of every Australian embassy and guided me through my 34-year career in international relations’.

The next posting, to East Germany, produced memoir gold: a 900-page file on Boyd created by the State Security Service. When she got the file in 2006, Boyd relived detailed records of her conversations and movements. Here’s her Stasi profile:

[She] appears uncomplicated, open and empathetic. She is single, dresses well, is interested in men, has a lot of male friends, but does not seem to have a particular boyfriend. She is at ease in men’s company … She enjoys food and eating, but does not drink much. But this is not from a prudish point of view, as borne out by the jokes she tells.

The file reinforced for Boyd the need for extreme care with ‘state-sponsored surveillance of citizens’ because of ‘how easy it is to reach wrong conclusions and make false assumption based on incomplete information and context’.

The chapter on ‘being a woman’ is a masterful meditation on career strategy. The External Affairs Department she joined in 1970 was a conservative and sexist minefield, ‘half-heartedly’ recruiting a token number of women who were still paid 10% less than the blokes.

Boyd became ‘firm, insistent and self-promoting’, learning from her initial mistake of trusting the department to recognise her talents: ‘We danced the constant dance of upsetting the men as little as possible so that they would become allies rather than adversaries.’ Part of the dance was to ‘be as blokey as the blokes,’ she writes, debating sport and employing rough jokes ‘as shock and awe tactics’.

When Boyd became the department’s spokesperson in 1990 (head of public affairs), such tactics still worked. She had to brief the foreign minister each day before parliament’s question time, and even the formidable Gareth Evans was ‘agitated and edgy’ when preparing for ‘questions’, the period when parliament goes freestyle for argument, abuse and advocacy:

On my first day working with him, he berated me and the department on a grammatical error in a briefing. ‘Haven’t you read the fucking style manual? It should be “first”, not “firstly”.’

I asked whether he was as concerned about the use of ‘presently’ in place of ‘currently’.

‘No’, he said. ‘Is that one of your concerns?’

I said it was.

‘Well, I don’t care about your concerns. I’m the fucking minister, not you!’

I calmly replied, ‘For the moment, Gareth’. (An election was due). There was an electric silence in room, and I thought, ‘Oh shit, now I’ve blown it’. But then he roared with laughter. ‘Well said!’ Everyone else in the room laughed, too. And I was launched.

Boyd rates Evans the best of the 12 foreign ministers she served. She used two briefing approaches on Gareth: the governess who ‘could firmly bully him back, calmly encourage him to settle down and focus on the material’ or surprise him with a tough jibe to force the minister ‘to stop and regroup’. Shock and awe, indeed!

Boyd writes that in the 1990s, DFAT’s culture shifted and she banished the blokeyness: ‘things had changed in the public service, and I needed to adjust my style’.

The trail that Boyd helped blaze means that over the five years to December 2020, the proportion of females heading DFAT’s missions and posts has risen from 27% to a record 43%. A year ago, a permanent exhibition was created on the ground floor of DFAT’s R.G. Casey Building, with pictures of women who’ve been the first to hold those jobs. One picture is of Boyd, who did the deed three times, as the first woman to head missions in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Fiji.

If you can’t be what you can’t see, the women of DFAT now see many pictures of what they can be.