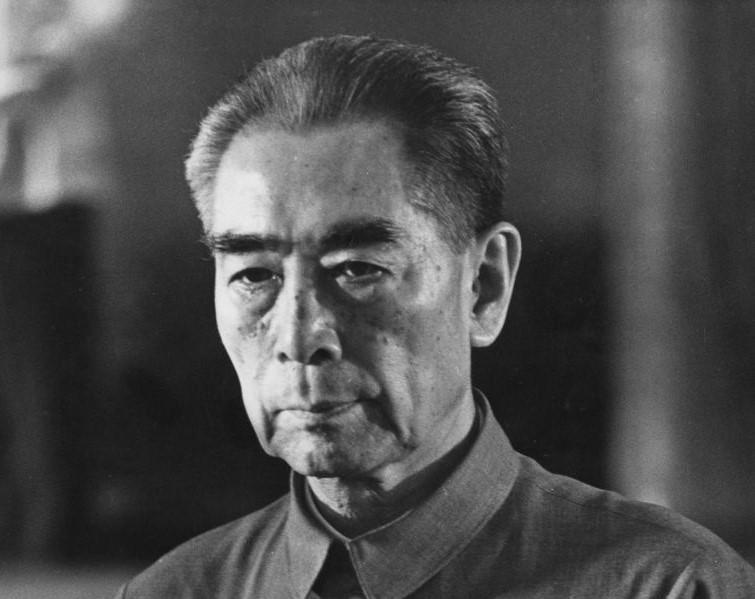

Zhou Enlai was a giant of twentieth century international relations. Serving as China’s premier from the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949 until his death in 1976 and also as China’s first foreign minister, Zhou set up China’s foreign service and skilfully guided China through the international events of the entire Mao Zedong era.

Zhou was a key member of the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership already in the 1920s, outranking Mao initially. He quickly established himself as the CCP’s indispensable person for getting things done. Later, as premier and foreign minister, he laid the foundations for China’s role as a leader of the global south in the 1950s, managed the Sino-Soviet rift in the 1960s, and was key to the opening of relations with the United States in the 1970s, helping to turn a crucial page in China’s history.

Zhou was the consummate political survivor. Under the mercurial Mao, this was no mean feat, as demonstrated by the fates of Zhou’s contemporaries. Following ideological disagreements in the wake of the disastrous Great Leap Forward, Mao shunned his anointed successor, Liu Shaoqi, who was detained by Red Guards and died in captivity. Lin Biao, another designated successor, was killed in a plane crash while fleeing the country following a power struggle, while Deng Xiaoping was purged twice, before rising to power following Mao’s death.

In stark contrast, Zhou learned to swallow his pride and was ultimately subservient to Mao. At the same time his diplomatic and organizational skills made him indispensable. However, Zhou’s record is mixed. He played a key role in tempering the chairman’s worst political excesses, particularly during the Cultural Revolution, and paved the way for the subsequent opening of China’s economy. But through his unwavering support he also facilitated Mao’s tyranny.

How did Zhou manage to survive over half a century of political turmoil, while at the same time deftly ushering China onto the global stage?

In Zhou Enlai: A Life, Chen Jian answers this question and many more. Chen is a professor of history at New York University and an emeritus professor at Cornell University. He spent the better part of 20 years researching this vivid and nuanced biography of a leader described by US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger as ‘one of the two or three most impressive men I have ever met’.

Zhou’s complex relationship with chairman Mao is at the centre of Chen’s narrative. In the 1920s at the CCP headquarters in Shanghai, Zhou was reluctant to become the head of the CCP, setting a pattern that would mark his entire career as the steadfast number two. On economic policy and even ideology, the moderate and reform-minded Zhou and the chairman never quite saw eye to eye.

The manipulative Mao used and abused the relationship, never entirely trusting Zhou. To survive the chairman’s whims, Zhou accepted frequent debasement and reprimands while only rarely receiving praise. When Zhou was diagnosed with gallbladder cancer in 1972, Mao prevented him from receiving potentially lifesaving surgery. It is widely assumed that Mao did not want Zhou to outlive him.

Throughout his career Zhou skilfully managed events, with a keen eye for detail. During the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, he ensured that the Zhongnanhai leadership compound and the cultural treasures of the Forbidden City were protected from rampaging Red Guards.

Zhou’s list of international achievements is vast. He negotiated sensitive border issues with Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru, managed conflict-ridden relations with Soviet leaders Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev, established ties with newly independent emerging economies and opened up relations with the West. As premier, Zhou also handled domestic issues. He led the drafting of China’s first five-year plan and worked hard to counterbalance Mao’s policy swings and mitigate the damage caused by the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Chen also provides a Chinese perspective on the behind-the-scenes negotiations leading up to Nixon’s visit to China, which have been extensively covered from an American perspective. The early stages were particularly sensitive, with both sides inching their way towards negotiations and neither side wanting to lose face.

In late 1970, Zhou arranged for major Chinese newspapers to publish a picture of Mao meeting the American journalist Edgar Snow, intending to send a sign to the Americans. At the time serving as national security adviser, Henry Kissinger missed the signal and later admitted that the Chinese ‘overestimated our subtlety’. To ensure that everything went to plan, in the ‘ping-pong diplomacy’ that followed, Zhou ordered the Chinese players to ‘let the American players win a few games’.

Chen provides a fascinating account of the wrangling within the CCP that deepened the rift between Mao and Lin Biao, and of the power struggle within the top leadership as Zhou and Mao both prepared to ‘meet Karl Marx’. As Xi Jinping advances in age and China’s younger leaders position themselves for an eventual succession struggle, these lessons will become increasingly relevant.

The lives of China’s top leaders, including Mao and Deng, have been extensively covered, but a comprehensive account of Zhou’s life has been a long time coming. Thoroughly researched, detailed and balanced, in Zhou Enlai: A Life, Zhou finally has the biography he deserves.