Once again, the Australian government has delivered exactly the funding it promised in the 2016 defence white paper and 2020 defence strategic update (DSU). If the government was willing to recommit to the white paper’s funding line in the depths of the Covid-19 recession, it was very unlikely to walk away from it now that the economy is recovering faster than expected.

As shown in ASPI’s 2021–2022 Defence budget brief, the consolidated funding line (including both the Department of Defence and the Australian Signals Directorate) is $44.6 billion, which is real growth of 4.1%. It’s the ninth straight year of real growth and, according to the DSU’s funding model, that will continue until the end of the decade.

Last year, defence funding hit 2.04% of GDP, meeting the government’s promise to restore the defence budget to 2% of GDP by 2020–2021. This year, it’s projected to reach 2.09%. Both of those numbers are smaller than predicted a year ago, as GDP has recovered faster than expected. It’s a salutary lesson on why we shouldn’t obsess too much about small changes in percentages of GDP.

Last year’s budget planned a substantial $3 billion or 27% increase to Defence’s acquisition spending. That was always going to be challenging in the middle of a pandemic that was disrupting global supply chains. During the year, the government and Defence reprioritised spending, both as a Covid-19 stimulus and to keep projects moving, but in the end the acquisition program ended up around $1 billion short, once exchange rate adjustments are taken into account.

Despite that, the military equipment, facilities and information and communications technology acquisition programs all set spending records. Overall, it was a 13% increase on the previous year. That’s quite an achievement in the middle of a pandemic. It’s a very encouraging sign that industry can meet the challenge of ‘eating the elephant’ presented by the DSU’s growing acquisition program. Australian defence industry did particularly well, according to Defence’s data. Defence’s local military equipment spend grew by a remarkable 35% to around $3.5 billion. Australian industry isn’t just growing in absolute terms: there are also signs that it’s growing in relative terms compared to the share of spending going overseas. If that continues, it’s evidence at the macro level that the government’s defence industry policy is delivering.

There’s another $3 billion increase in acquisition spending planned this year. If the recovery from Covid-19 continues, Defence and industry could come close to achieving it.

The sustained spending is delivering capability. At the end of last year, the F-35A reached the key milestone of initial operational capability. It will reach its full capability in late 2023 after a 21-year journey. The air warfare destroyer project will also reach full capability very soon. There are substantial upgrades to Defence’s facilities occurring around the country.

The naval shipbuilding program is aiming to spend $2.5 billion this year, and its biggest element, the Attack-class submarine project, is looking to hit $1 billion for the first time. The naval shipbuilding enterprise will most likely reach $4 billion in annual spending by the time the submarine and future frigate programs are into construction. But that also means that those projects will have spent tens of billions of dollars between them by the time the first submarine and frigate are operational.

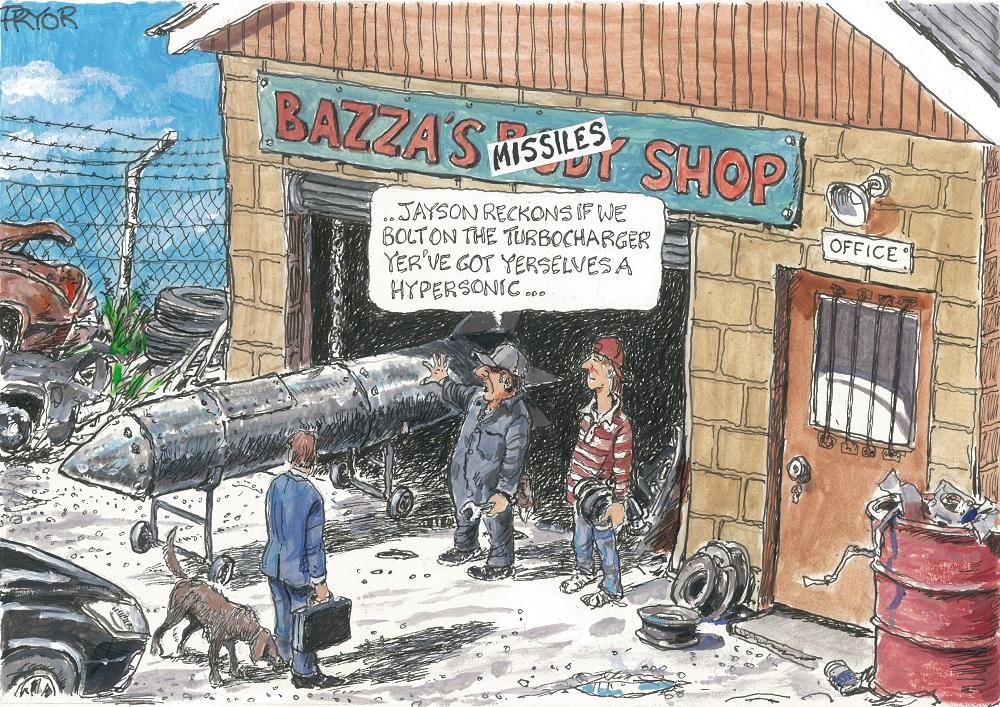

The government’s recent announcement that it will accelerate the establishment of a domestic guided weapons manufacturing capability in Australia was big news. With $100 billion in investment in guided weapons planned and the policy and industrial fundamentals for local production in place, there are good prospects for a huge leap forward for military and industrial capability and the mitigation of supply-chain risks. Getting it right is important, but Defence should also start quickly with some low-risk projects to produce existing types of weapons.

But fundamental problems remain in Defence’s capability acquisition system. Earlier this year, Defence cancelled its project to deliver the Submarine Escape Rescue and Abandonment System. After getting into contract and spending what could be close to $100 million, Defence decided that it had irreconcilable differences with its industry partner.

The army’s highest priority program, digitisation, also has been put on hold after nearly 15 years of work and almost $2 billion spent. Even if it continues, LAND 200 could take another 10 years to complete—in total, that’s longer than the F-35A. Can Defence keep running projects that take a quarter of a century to deliver?

Defence’s external workforce is now its biggest ‘service’, ahead of the army. And there’s a looming iceberg in there. Defence’s acquisition and sustainment budgets are planned to double over the decade. Local acquisition spending alone could grow from $2.6 billion to around $10 billion. Defence will need a much larger workforce to run those activities, but its own workforce is capped, so it’s increasingly having to turn to contractors. There’s very little data available on what individual contractors cost, but it could be well over twice the average cost of public servants. Collectively, it could cost $1 billion more than an equivalent number of public servants today.

While Defence’s top-level budget breakdown shows that the cost of its workforce is declining as a share of the overall budget, that’s potentially misleading; the costs of growing numbers of contractors show up not in Defence’s personnel budget but in its acquisition and sustainment budgets. It’s hard to tell, but it’s possible that over 10% of Defence’s acquisition budget is going to contractors helping to run projects. Overall, the cost of contractors could explode and eat deeply into Defence’s acquisition budget. Defence needs to fully understand the value-for-money case for using contractors—and it needs to share that with parliament.

While there are significant questions about how efficiently Defence is spending, there are even bigger questions about whether it’s spending on the right things in the first place.

We noted last year the fundamental disconnect between the strategic assessments in the DSU and the capabilities presented in the supporting force structure plan. The DSU emphasised the need for long-range strike capabilities that can impose cost on and deter a great-power adversary at distance. Yet the ADF’s strike cupboard is bare, and there’s no clear path to restock it quickly. Huge investment is also planned in capabilities that appear to have minimal deterrent effect on a great-power adversary, such as up to $40 billion on heavy armoured vehicles.

The force structure and timelines for delivery are holdovers from previous strategic planning documents developed in circumstances that bear little resemblance to our current one. Fundamental changes to concepts and force structure, such as making greater use of uncrewed and autonomous systems, are occurring only slowly. The vast bulk of investment is still going into small numbers of exquisitely capable yet extremely expensive crewed platforms that take years, even decades, to design and manufacture and are potentially too valuable to lose. Defence needs to take more risk and invest more than half of one percent of its budget in research and development, particularly in distributed, autonomous technologies.

The government has delivered the steadily increasing funding it promised at the start of 2016. That’s commendable, considering the economic impact of Covid-19. However, in the DSU, it also acknowledged that Australia’s strategic circumstances have deteriorated since 2016—yet Defence’s funding model hasn’t changed since then.

More funding is needed, but Defence will need to show that it can use it well to deliver capability rapidly. Over the decade, the government is providing $575 billion in funding to Defence, but in that time it won’t deliver a single new combat vessel. In short, Defence will need to demonstrate that it has absorbed and is acting with the sense of urgency presented in the DSU.

A final note that shows that part of the DSU’s intent is being realised. The DSU directed Defence to focus on our immediate region. As consequence, operations in the Middle East are drawing down and spending on operations is now at its lowest level since before the ADF deployed to Timor-Leste in 1999.