The death of George H.W. Bush has inspired high praise from across the international political spectrum. This is largely because America’s 41st president (1989–1993) was almost above politics as we know it today. ‘[B]y temperament a man of the middle in an age of increasing ideological polarization’, is how the Wall Street Journal editorialised Bush Senior. ‘[A] gentleman in a culture growing cruder by the year… [and] a man of admirable private and public character who believed in government service for the good of the country and not merely for power.’ All true.

However, I believe there is another reason for the glowing tributes: Bush Senior was the last president, with secretary of state James Baker and national security adviser Brent Scowcroft at his side, to grasp the complexities of foreign policy. He was the quintessential realist during idealistic times. Let me provide just two examples: Iraq and Soviet Russia.

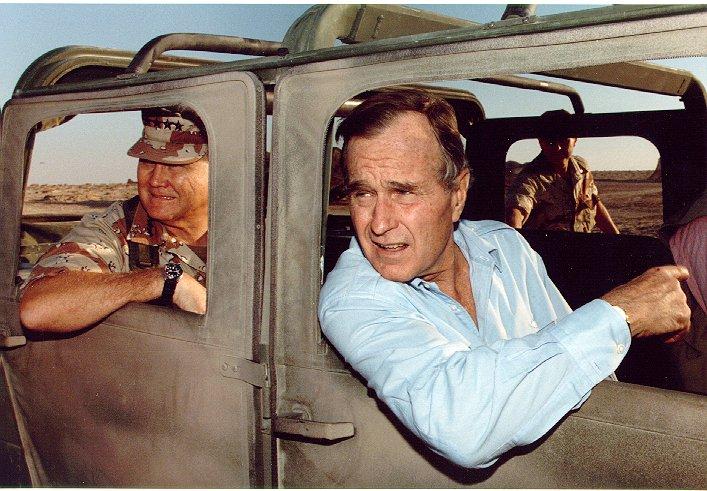

After Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, Bush took the lead in organising the US-led multinational response. It produced the swift and decisive victory in the Persian Gulf War of early 1991. He was criticised for not intervening when the Iraqi tyrant began slaughtering Shia and Kurds after the US-led liberation of Kuwait. Prime Minister Paul Keating in 1994 was among those who expressed disappointment at the failure to ‘finish him [Saddam] off’. However, the goal, as Bush—and indeed Bob Hawke, who led the Australian war effort—always made clear, was never to topple Saddam or democratise Iraq; it was about restoring order and stability to that part of the world.

Like most realists, Bush, Baker and Scowcroft believed that although containment—sanctions, naval blockades, no-fly-zones—may have lacked the political sex appeal of ‘liberation’, at least it would avoid the unintended consequences of a liberated Iraq. Look at Iraq since the invasion of 2003 and you can see what they meant: high costs in blood and treasure, a Shia ascendancy along with strengthened Iranian power and influence in Iraq, and marginalised Sunni Iraqis who turned to an insurgency that morphed into a plethora of jihadist groups.

With the end of the Cold War and the demise of Soviet communism, Bush rejected triumphalism in favour of caution. Far from maximising American advantage, he was focused on managing the collapse of an empire lest it unleash the kind of instability, chaos and bloodshed usually associated with the fall of empires. (Think of the British departure from Kenya, Malaya and the Indian subcontinent, or the French from Vietnam and Algeria, or the Belgians from Congo.)

American liberals and conservatives alike slammed Bush for failing to celebrate the end of the Cold War and embrace national self-determination among the Soviet republics more enthusiastically. Shortly after Eastern Europe was liberated in November 1989, for instance, Democrat Senate majority leader George Mitchell called on Bush to fly to West Berlin ‘to acknowledge the tremendous significance of the symbolic destruction of the Berlin Wall and to give voice to the exhilaration felt by all Americans’.

Such criticisms of Bush’s realpolitik reflected the spirit of the times. From left to right, journalists and intellectuals were celebrating the victory of Western liberal democracy, dismissing the importance of stability and predictability and drawing comparisons between America’s global predominance and that of Rome. These were the days of ‘the end of history’ (Francis Fukuyama) and the ‘unipolar moment’ (Charles Krauthammer).

But the triumphalist worldview was alien to Bush, a balance-of-power realist whose low-profile use of US diplomatic and economic leverage over the Kremlin constrained Mikhail Gorbachev’s ability to crack down on nationalist movements in the Baltics. Bush was no wimp, as he was sometimes derided, but he recognised the folly of grinding the face of a defeated foe in the dirt. ‘I did not want to encourage a course of events which might turn violent and get out of hand’, he later recalled in his memoirs, co-written with Scowcroft. For Bush, the enemy was unpredictability and instability.

Which brings me to what distinguishes Bush Senior from his post–Cold War successors: his realism. According to foreign-policy realists, America is not a ‘new Israel’ but one nation among others and should be guided by national strategic and economic interests, pursued with a pragmatic calculation of commitments and resources.

Its goal should not be to impose its democratic ideals on other nations but to secure peace and stability by maintaining a balance of power among potential adversaries. Not for realists any noble, grand causes to transform the world in a democratic image.

It’s fair to say that realism has provided a sound alternative to the excesses of American idealism, whether it was overextension in Vietnam or aggressive unilateralism and democracy promotion in Iraq. And in the hands of Bush, Scowcroft, Baker and other advisers such as Lawrence Eagleburger, Colin Powell and Richard Haass, realism was an important corrective to the fog within which Wilsonian idealism and a Pax Americana has shrouded US foreign-policy discourse for much of the post–Cold War era.

Americans today could do worse than heed Bush’s counsel about the importance of allies, the danger of hubris, illusions of omnipotence, and the wisdom of limits, restraint and modesty in a messy and pluralistic world.