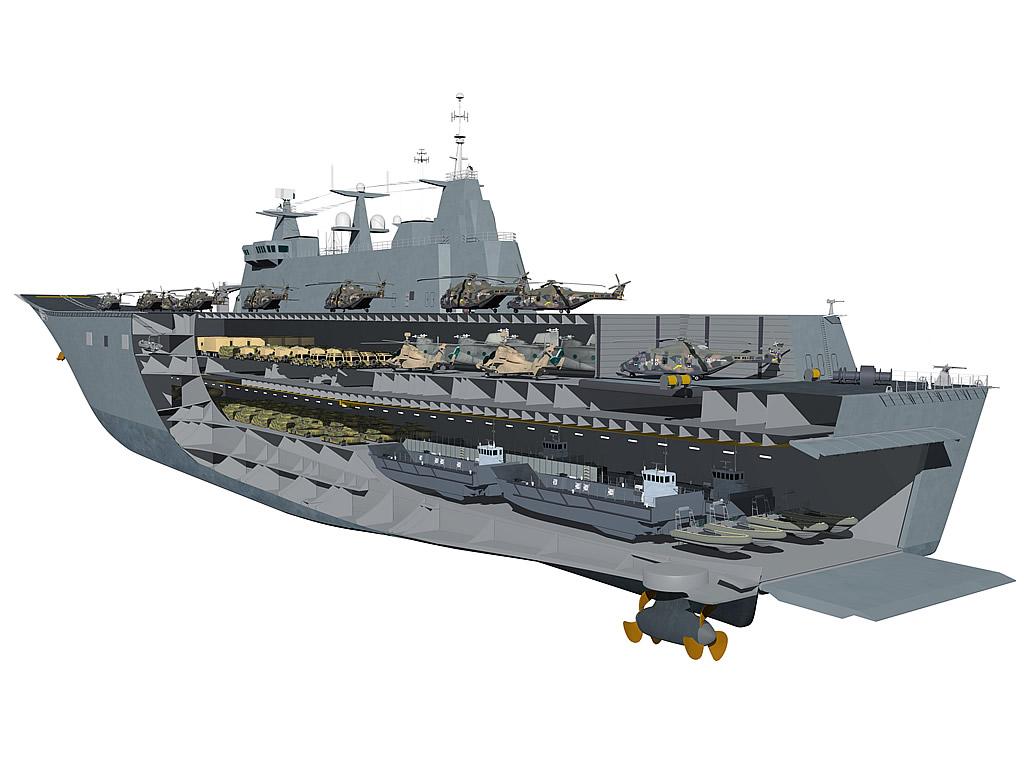

There has been quite a spirited debate (here and here) about the meaning behind the largest ships ever built for the Royal Australian Navy. In thinking about this further, maybe we should return to more operationally focused thinking. Basically these ships simply provide a sea transport capability, but with the special feature of being able to get the stuff on them off them using organic means.

There has been quite a spirited debate (here and here) about the meaning behind the largest ships ever built for the Royal Australian Navy. In thinking about this further, maybe we should return to more operationally focused thinking. Basically these ships simply provide a sea transport capability, but with the special feature of being able to get the stuff on them off them using organic means.

The LHDs aren’t capital ships, a primary type of ship in a naval fleet able to engage and sink other vessels. They’re not warships in that sense at all, being very vulnerable to almost any form of attack. Sailing in an area where attacks were possible they’d need to be defended by numerous other vessels—which themselves would need support from accompanying naval tankers and land based aircraft of varying kinds. Jim Molan has a point when he says that the ADF can ‘use these (LHD) ships to create around them a truly joint ADF that can actually fight and win in sophisticated joint warfighting operations’. Keeping the LHDs afloat in the face of a sophisticated enemy would indeed be a very demanding joint warfare task.

But LHDs (surely) exist for more than just to attract enemy naval and air commanders keen on sinking a large gray transport ship. What is it that’s so important?

Firstly, while the RAN is getting two LHDs, the need for maintenance and refits means that often only one would be available for operations. And such large ships have high operating costs, so even keeping one operational might force the Navy to prioritise its operating budget away from surface warships and submarines towards LHD maintenance and support. This isn’t just a matter of money, as the Coles and Rizzo reports revealed that there’s also a heavy demand for skilled staff and intellectual effort. There’s a danger that, just as when the Navy operated a fixed wing aircraft carrier, the fleet, its doctrine and its capabilities will end up being focussed around a single ship and its limited range of missions.

But there’s a cunning plan to help avoid too heavily skewing the Navy’s operating budget and thinking towards sea transport. The LHD’s air wing of between eight and 18 medium helicopters will be mainly provided by the Army at its expense. To provide such substantial shipborne helicopter elements, the Army will need aircraft embarked on the LHD(s), aircraft in maintenance and aircraft being used to train and work up crews for future embarkations. If the ADF was to aim for 18 embarked helicopters, a few simple sums suggest that the lion’s share of Army’s 46-strong MRH-90 fleet will be absorbed in supporting just one LHD. These numbers can be played with, but the point is that a sizeable fraction of the Army’s helicopter force seems likely to be semi-permanently assigned to a sole operational LHD. Over time the Army as an organisation may also become skewed more towards meeting the demands of the LHDs than training for conventional warfighting.

What’s the payoff for all this pain? The ships will be able to transport about 1,000 military personnel, comprised of soldiers and those involved with the helicopter operations. These soldiers will initially be from the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (2 RAR) based in Townsville. The small numbers suggest that Andrew Davies may be right in arguing that the LHD’s main military role could be assisted or protected evacuations. In the age of globalisation, recovering stranded Australians, whether tourists, expatriate businessmen or mining staff, is a function that governments can’t ignore.

Such an operation occurred in June 2000, when the landing ship HMAS Tobruk embarked 486 civilian evacuees from Honiara in the Solomons and took them to Cairns. Other less well-equipped nations used chartered civil air transport to fly their nationals from Honiara to Townsville in a few hours. Using an LHD in such an evacuation role will require having the ship manned and equipped and deployed well-forward—like the USMC is well practised at doing—but that’s not an inexpensive business. A straight forward task perhaps in the Solomons case, but a more problematic one in Australia’s 2006 civilian evacuation operation in Lebanon, which involved 5,200 people.

But maybe Andrew’s wrong. Maybe the LHD’s main role will instead be sea transport of troops and supplies to distant lands for peace keeping or humanitarian operations. ‘Doing Somalia’ logistically better than in 1992 does seem a more realistic function for the two LHDs. Indeed Somalia involved an LHD-sized 1,000 strong infantry battalion group, and the echoes continue, with the commander of that group now CDF.

This returns us to where we started. The LHDs appear more suited for operations-other-than-war than for warfighting. Using them in any major conflict would be a difficult, uncertain business with a limited payoff. A good thing perhaps that a major conflict looks rather improbable, but then real capital ships or more fast jets might have been acquired if that was anticipated.

To my eye then, the LHDs are best suited for the more likely tasks the ADF may be called upon to undertake in the next couple of decades—not the most dangerous or the most important. Forget using them to defend Australia from invasion; the LHDs are for the more pressing, albeit somewhat prosaic, task of transporting people and stuff around. More provocatively, one might ask transport to where? The last 100 years of our military history suggests the Middle East might be the favoured destination.

Oh yes, a last thought on risk. Andrew thinks Jim and Neil James want to retire risk. In the LHD’s case this isn’t what they’re best for, nor acquired for. The LHDs can be used to respond to overseas events, but the ships can’t in themselves stop risks eventuating.

Peter Layton is undertaking a research PhD in grand strategy at UNSW, and has been an associate professor of national security strategy at the US National Defense University. Image courtesy of Department of Defence.