With voting underway in the US, the eyes of the world are focused on America’s democratic process.

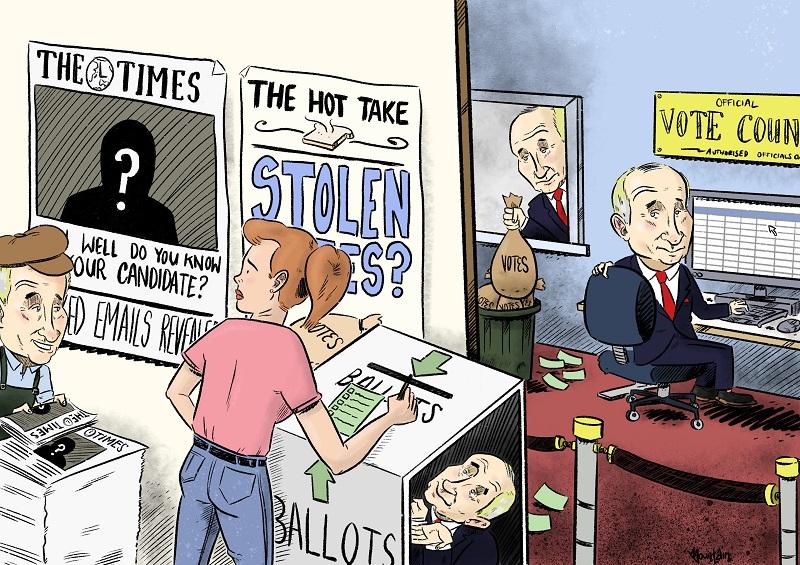

Unfortunately, so is the attention of groups of state-backed hackers from around the world as the US’s adversaries seek to interfere in the election.

In the last fortnight, the FBI, the Director of National Intelligence and the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency publicly attributed another cyberattack on the 2020 election to Iranian hackers.

Emails using the threat of violence to coerce voters’ behaviour began arriving in the inboxes of registered Democrats in Alaska, Arizona and Florida. They purportedly came from the far-right Proud Boys group, but actually originated from Iranian state-backed hackers.

This attack follows the successful hack-and-leak campaign undertaken by Russian-backed hackers against the 2016 US election and are part of an accelerating trend we’re seeing around the world. One where nation-state hackers are targeting the IT systems of non-governmental democratic institutions in an effort to interfere in other countries’ democratic process.

As ASPI’s recently released report Cyber-enabled foreign interference in elections and referendums notes, these operations have emerged as a high-impact and increasingly common threat to sovereignty in democracies.

Similar attacks have occurred since 2016 in the United Kingdom, France, Germany and many other democratic nations.

Indeed, ASPI has found that 41 elections have been targeted by cyber-enabled operations in the last decade.

They are a salutary warning for Australia.

More often than not, the targets of these hacks are not government or parliamentary IT systems, but other institutions of democracy—political parties, media outlets, research institutes and non-governmental organisations.

A recent report from Microsoft found that NGOs were the most common targets for state-backed cyber operations, constituting 32% of all targets.

Australia is currently unprepared for cyberattacks on democratic institutions outside government. Something similar to Iran’s ‘Proud Boys’ effort would be easily replicable in Australia through attacks on the IT infrastructure of Australia’s political parties.

After the February 2019 cyberattacks on the networks of Australian Parliament House and the major political parties, Prime Minister Scott Morrison told parliament that our democratic process was ‘our most critical piece of national infrastructure’.

But today, while the government does consider the IT systems of Parliament House and the Australian Electoral Commission critical infrastructure, it doesn’t extend this to the IT systems of the other organisations targeted in this attack—Australia’s political parties.

The Morrison government has offered band-aid fixes to this problem over the past three years, including $2.7 million over four years allocated to the major parties’ cybersecurity in the 2019 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

However, Australia lacks an ongoing institutional framework to build resilience against cyberattacks on non-governmental democratic institutions.

The cyber resilience of these institutions falls through the cracks of our current security arrangements.

Government security agencies provide robust cybersecurity protections for parliamentary email systems, but these protections stop when MPs use private emails, social media accounts, privately hosted websites and smartphone apps.

Home Affairs, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, the Australian Signals Directorate and the Department of Parliamentary Services all have some indirect responsibility here, but none take ownership of the issue.

While I’m sure there would be a significant incident response in the wake of a successful attack, there’s little being done to prevent attacks in the first place—or to build resilience through our information system to mitigate the impact of such attacks once they occur.

There’s no capacity-building program for our democratic institutions, no targeted cyber hygiene training, no real-time sharing of threat intelligence, no assistance with vulnerability assessments, no monitoring of logs.

Nor are there any public awareness campaigns on the nature of this threat to our sovereignty, or any clear institutional responsibility for identifying and informing the public about cyber-enabled foreign interference. The government hasn’t even given any advice on which smartphone apps to avoid.

The government recently released a consultation paper on Australia’s arrangements for protecting critical infrastructure and systems of national significance.

This paper frames an expanded definition of critical infrastructure as infrastructure supporting services ‘crucial to Australia’s economy, security and sovereignty’.

Despite the demonstrable threat that cyberattacks on non-governmental democratic institutions pose to our sovereignty, the paper fails to address this challenge.

This oversight is striking in the context of a recent speech by Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton to The Age and Sydney Morning Herald’s National Security Summit in which he correctly warned of the threats to democratic institutions from foreign interference.

Yet when the vector is a hack-and-leak campaign against these targets, the government remains blind to the threat.

As a result, these non-governmental democratic institutions are left to face advanced persistent threats from sophisticated state-backed hackers largely on their own.

It’s not a fair fight, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

The Morrison government likes to talk big on fighting foreign interference, but if it’s serious it must start taking the threat of cyberattacks against non-governmental democratic institutions seriously.