High expectations for Indonesia’s ASEAN chairmanship

Posted By Teesta Prakash and Gatra Priyandita on December 20, 2022 @ 14:45

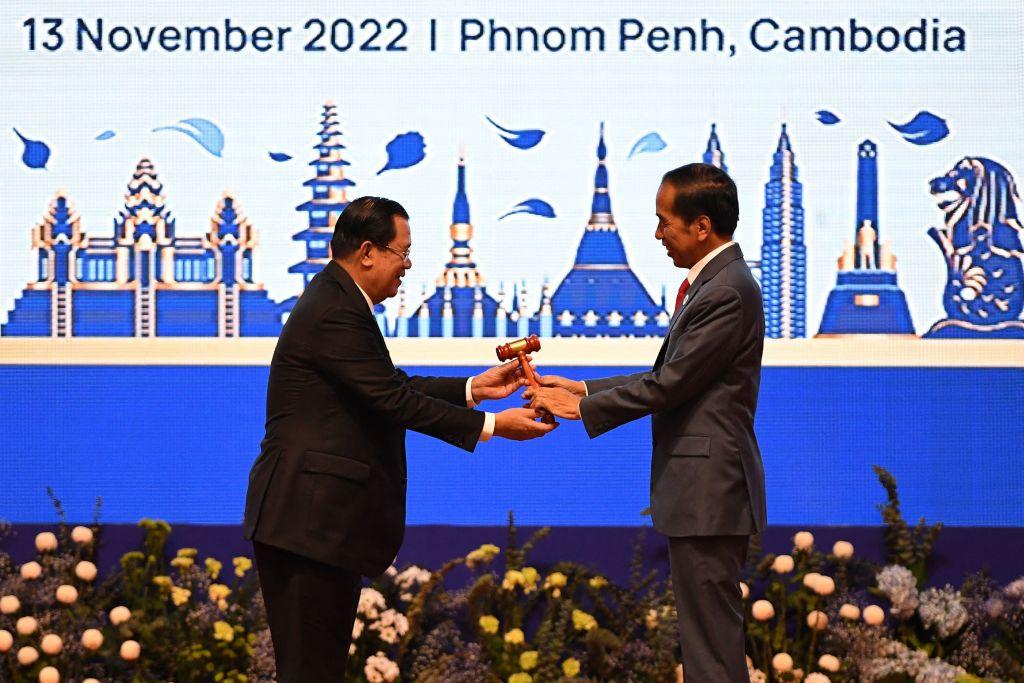

Last month, just days before hosting the G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia was officially named as chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations for 2023.

In chairing ASEAN, Indonesia will play a pivotal role in setting the agenda for the hundreds of meetings ASEAN regularly hosts each year for its 10 member states, as well as the 27 other countries that are regularly engaged as dialogue partners and as members of ASEAN’s ‘plus’ mechanisms, like the ASEAN Regional Forum. President Joko Widodo, who is normally uninterested in foreign affairs, will also have the opportunity to (once again) play the role of international spokesman after globetrotting as the face of the G20 in 2022.

So, what’s likely to be on the agenda in 2023?

At the very top is post-Covid-19 economic recovery and economic cooperation. Widodo announced the theme of Indonesia’s chairmanship as ‘ASEAN matters: epicentrum of growth [1]’. The theme is, in many ways, a response to two sources of insecurity for ASEAN that relate to its relevance in the 2020s: the association’s diminishing voice in an era of great-power competition, and the ability of the association to offer economic benefits to its 684 million people.

In response to the latter, officials have long been working to deepen economic integration to bolster regional economic growth, encourage intramural trade flows and strengthen ASEAN’s power as a bloc. In the past, attempts have been undermined by a lack of enthusiasm to break down tariff and non-tariff barriers. However, the Covid-19 pandemic has given impetus for states to address mutual concerns regarding supply-chain resilience and digital trade. While Southeast Asia has done relatively well [2] in recovering from the pandemic, disruptions in global value chains have hit its manufacturing centres hard, forcing governments to assess the long-term security of supply chains.

Indonesia will likely focus on ensuring commitments to meeting the ASEAN 2025 vision [3], particularly provisions that relate to digital connectivity and trade. The Covid-19 pandemic has increased the pace of digital transformation in the region, and thus accelerated cyber dependency.

What may be the centrepiece of the Indonesian chairmanship, however, is the ascension of Timor-Leste as a full member of ASEAN. After more than a decade of lobbying, Timor-Leste achieved a major diplomatic win at the 2022 ASEAN summit when it was able to get other member states to agree in principle to accept its application for membership. Indonesia has been the strongest advocate for Timor-Leste’s membership of ASEAN and Jakarta will want to see its ascension as soon as possible.

However, Indonesia’s success as ASEAN chair will likely be assessed based on how it manages two big challenges. The first is the ongoing turmoil in Myanmar, which has not only dominated discussions within ASEAN but also been a topic of international concern. ASEAN’s attempts to address the situation through a five-point consensus [4] has largely failed; the junta continues to commit acts of violence. With Myanmar scheduled to have (likely rigged and unfair) general elections in 2023, there will be high expectations that Indonesia will apply more pressure on the junta.

The second major challenge is dealing with the strategic implications of Sino-American rivalry on Southeast Asia. Widodo has said that ASEAN’s key objective under Indonesia’s chairmanship will be ‘not to be a proxy to any powers [5]’. That statement follows a trend [6] among Southeast Asian leaders of expressing serious concern and anxiety about the effects of great-power competition on ASEAN’s strategic autonomy.

While the US and China seem to have had a temporary moment of rapprochement following the meeting between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping in Bali, great-power rivalry still has the potential to compound regional economic and security concerns. For example, the attempted technological decoupling of the two powers may disrupt Southeast Asia’s information and communications technology ecosystem, which depends on support, resources and technical knowledge from Chinese, Japanese, European and American tech firms.

There’s also the need to face other potential volatilities, like the South China Sea disputes—the central security flashpoint in Southeast Asia. Indonesia has already sought to coordinate regional efforts [7] to redress this balance of power in the region. However, given the internal contradictions within ASEAN’s members and their varying levels of distrust of China, a common policy approach, or consensus, could be hard to find, and that could be beneficial to China [8].

Southeast Asia’s relationship with China is a complex one with competing geostrategic and geoeconomic priorities. The region’s priority remains economic development as it faces massive infrastructure gaps, and China is funding key infrastructure projects across many sectors, including transport (high-speed rail [9] and bridges [10]) and energy (power plants [11], often coal powered). China has substantial economic influence and heft in the region.

Yet China is also strategically challenging the sovereignty of the countries in the region through its behaviour in the South China Sea. Indonesia is aware that a unified ASEAN bloc, and indeed a cohesive Southeast Asia, would be the best deterrent against an assertive rising China, and that will be its single most important challenge—to bring cohesion to the region, economically as well as strategically. Its success will be measured by how it bridges the strategic and economic dissonance in 2023.

Given Widodo’s stated dual aim of not falling into the great-power competition and focusing on the region’s economic recovery, there are signs that Indonesia’s chairmanship will likely try to focus on regional connectivity as a means to achieve both aims, but that may be a challenging task. The push for Timor-Leste’s inclusion in ASEAN is likely to be driven by the strategic vision that no country in Southeast Asia should fall under any one power’s influence. Given the potential for Timor-Leste to fall under China’s economic influence [12], its inclusion in ASEAN could ensure that it diversifies its economy and integrates with the region, lessening its dependence on China.

Expectations are often (a bit too) high for the Indonesian chair. As the region’s largest country, Indonesia is often seen as the primus inter pares of ASEAN’s member states, each of which commands veto power over the association’s decision-making. Nonetheless, Indonesian diplomats will likely reflect on past symbolic successes. In 2003, the Indonesian chairmanship passed the Bali Concord II, which initiated plans to construct the ASEAN Community. In 2011, Indonesia laid the foundations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement—the world’s largest free-trade area—which came into effect on 1 January 2022.

With this being Jokowi’s (and, most likely, Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi’s) last ASEAN summit, we can expect some attempts at legacy making. But whether it’s about economic integration or Timor-Leste’s ascension, the Indonesian chairmanship will likely be faced with serious challenges beyond its control. Whereas the benchmark for success for Indonesia’s chairmanship of the G20 this year was its ability to run a meeting that was as ‘normal’ as possible in the face of major global challenges, the benchmark for success for an Indonesian chairmanship of ASEAN is much, much higher.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /high-expectations-for-indonesias-asean-chairmanship/

URLs in this post:

[1] ASEAN matters: epicentrum of growth: https://setkab.go.id/en/president-jokowi-encourages-asean-leaders-to-maintain-unity-centrality/

[2] done relatively well: https://www.afr.com/world/asia/asean-economies-a-bright-spot-amid-gloomy-outlook-20220921-p5bjtc

[3] ASEAN 2025 vision: https://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/2015/November/aec-page/ASEAN-Community-Vision-2025.pdf

[4] five-point consensus: https://asean.org/asean-leaders-review-and-decision-on-the-implementation-of-the-five-point-consensus/

[5] ‘not to be a proxy to any powers: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/asean-must-become-peaceful-region-and-not-be-proxy-for-any-power-indonesia-president-joko-widodo

[6] trend: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/2020-06-04/lee-hsien-loong-endangered-asian-century

[7] coordinate regional efforts: https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/indonesian/indonesia-china-south-china-sea-12282021153333.html

[8] beneficial to China: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3010790/divide-and-conquer-asean-china-tries-go-one-one-malaysia

[9] high-speed rail: https://abcnews.go.com/Travel/wireStory/indonesia-gears-start-high-speed-rail-line-91433113

[10] bridges: https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-govt-unveils-four-projects-part-chinas-bri-scheme.html

[11] power plants: https://chinadialogue.net/en/energy/vietnams-draft-power-plan-favours-coal-but-who-will-pay/#:~:text=China%20is%20the%20biggest%20financier,1%20is%20scheduled%20for%202023.

[12] China’s economic influence: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/greater-sunrise-can-timor-leste-play-china-card

Click here to print.