The character of the personal relationship between the American president and the Australian prime minister used to be a source of anxious speculation in Australian media and politics. It was an issue in particular for an opposition leader. Would he or she be capable of sustaining what was there for the moment? The advent of the Trump administration has seen a question mark rise over whether or not we might want that intensity, at leadership level. That has in turn exposed what matters more. The breadth and depth of the military and intelligence interconnection at the lower levels is the relationship’s real underpinning. However, close relationships at leadership level do help.

In my lifetime in politics, the deepest such relationship I saw was between John Howard and George W. Bush. Other pairings were good, but in my time in government it was the one between Prime Minister Bob Hawke and the recently passed George Shultz that really counted. A secretary of state, not a president. It was a personal relationship and preceded Hawke’s life in politics. They were friends in regular conversation—an outgrowth of meeting at the International Labour Organization when Shultz was Richard Nixon’s labour secretary and then took up senior positions at Bechtel Group. It became critical when Shultz replaced General Alexander Haig as Reagan’s secretary of state in 1982.

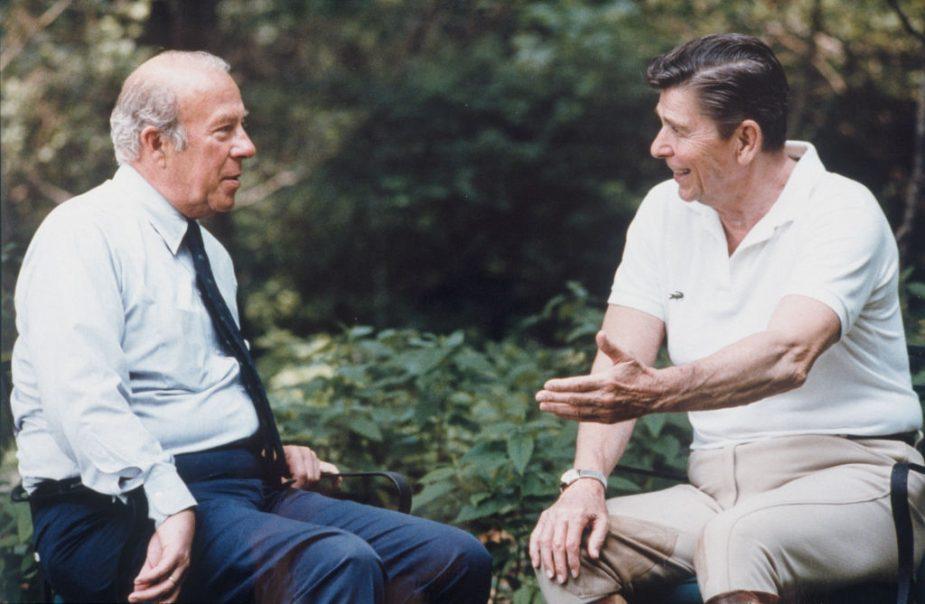

The Reagan administration and Hawke government were not a natural fit. The ministers who needed to built reasonable relationships with their US counterparts. Only Hawke’s relationship with Shultz was capable of turning a firm American direction on its head. Shultz trusted Hawke. More important, Reagan trusted Shultz. Nearly all the obituaries of the past few days attest ‘a great American statesman’ or quote Henry Kissinger in his memoirs: ‘If I could choose one American to whom I would entrust the nation’s fate in a crisis, it would be George Shultz.’ The only member of the administration who would contest his overarching status was my counterpart, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger.

The Hawke–Shultz relationship was tested in the first few months of Hawke’s second term in what was called the ‘MX-missile test crisis’. On becoming defence minister, I discovered the government had approved support for a test into Australia’s vicinity. Both Foreign Minister Bill Hayden and I had the view that we could not back off the test. At the time, the US was asking much harder things of British and European allies with the dispersal of cruise and Pershing ballistic missiles to answer a deployment of Soviet short- and medium-range missiles on its borders. We could not expect the US to back off.

Hawke thought our worries of public disapproval in Australia were exaggerated and took off for a visit to Japan and the US. As the visit proceeded, the story broke. Public anger ensued. Within 24 hours, the hard line out of Japan disappeared and so did Washington’s, altogether. Hawke wanted the test withdrawn—Weinberger’s department. Shultz was approached by Hawke with the argument that the test didn’t matter, the joint facilities did. This would escalate controversy around them. Shultz went in against every section of the administration, all apoplectic about the potential effect on other allies facing really hard decisions. In 24 hours, Shultz overturned it all. We were staggered. Hawke was irrepressible and proceeded in his meeting with Reagan to advise him on the unwisdom of the Strategic Defense Initiative.

Shultz saw me every time I was in DC while defence minister. The most memorable occasion was after the resignation in November 1986 of John Poindexter as national security adviser. Poindexter was caught up in the Iran–Contra affair. The administration was in chaos: members were deeply worried about the situation of the president and a number of gung-ho advisers. In his suite in the State Department, the secretary has a large fireplace-warmed lounge room. Shultz took me into it for an hour and frankly described the chaos in the administration. He spoke of his deep loyalty to Reagan, for whom he had deep affection. He said he and Weinberger had agreed to cease hostilities and work together to mitigate the impact of the crisis, stabilise national security policy and keep allies quietly briefed and reassured. Collectively, they had recommended and had accepted Frank Carlucci as national security advisor.

What struck me about Shultz was his deep respect for Reagan. He had a long association dating back to Reagan’s time as governor of California. When Reagan died, that care and concern was extended to Reagan’s widow, Nancy. She was deeply concerned to see championed Reagan’s horror of nuclear weapons. As Gareth Evans has attested, Shultz engaged with him and many others on a project to get nuclear weapon states to remove theirs. His own conviction had come to see that such destructive weapons had no place in human society.

I saw something of Shultz when I was Australia’s ambassador to the US. Early in my time, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd had him recognised with an honorary Order of Australia. I used to complain that he’d had it beautifully mounted on the brag walls of his offices at Stanford University: ‘You are supposed to wear them, George!’ Still proud of it, he said. As past notables, you don’t turn up in great American universities to be ornaments; you are there to teach. Well into his 90s he taught classes, one titled ‘The 10 principles of diplomacy’.

One of the last times I saw him, he took me up to his penthouse on the 36th floor of a block built on a San Francisco hill. I could hardly bear to go onto the balcony, my feet numb as I contemplated the drop and San Francisco’s record of earthquakes, my back firmly pressed against the wall. From there you could see the entire course of the forthcoming America’s Cup yacht race. When I could think again coming away from the visit, I thought about Shultz and the symbolism of that expansive view. He had multiple contacts and friends among the globe’s great and good, but he could also encompass the also-rans. For him, though, it was always about America, the globe and the safety and prosperity of humanity. We will struggle to see his like again.