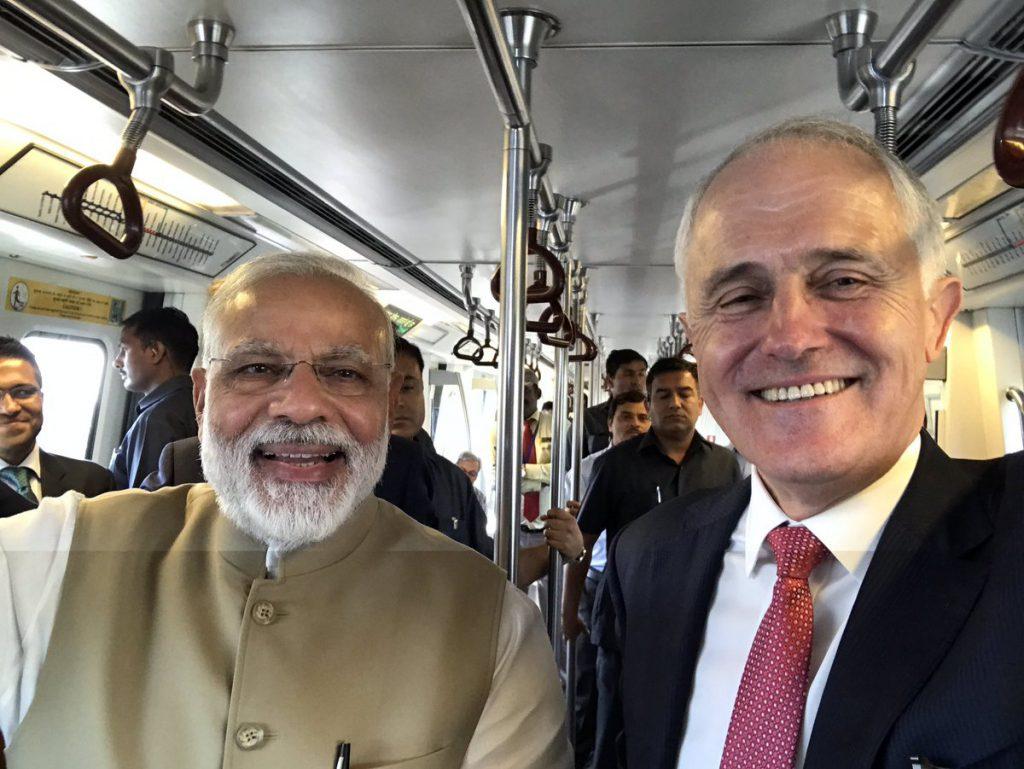

As India and Australia become closer, one of the ideas binding them over the longer term is the new framing of their shared geography—the ‘Indo-Pacific’. When prime ministers Narendra Modi and Malcolm Turnbull met in Delhi in April 2017, they reaffirmed their commitment to promoting peace and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific.

Critics of the Indo-Pacific construct say it’s too vast a space to be amenable to practical cooperation. One way of lending substance to the Indo-Pacific cooperation between India and Australia is to identify specific subregions, such as the Bay of Bengal. If you step back and take a look at the Indo-Pacific as a whole, the Bay of Bengal is right in the middle. As the western adjunct to the South China Sea, the waters of the bay connect the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Until the Bay of Bengal was reduced to a strategic backwater by the British Raj in the early decades of the 19th century, it was the site for major geopolitical contentions among the European colonial powers. The bay’s strategic significance was once again highlighted during World War II, when Japan overthrew the British and European primacy. The resources of the British Raj, the Commonwealth, the US and nationalist China had to be pooled together to oust the Japanese from the littoral and Southeast Asia.

Today, the Bay of Bengal littoral has once again begun to emerge as a strategic theatre. While the US remains the dominant force in both the Indian and Pacific oceans, it’s China that promises to transform the geopolitics of the littoral. Beijing has outlined ambitious plans for infrastructure development linking southwestern China to the Bay of Bengal. Beijing is also paying serious attention to securing what it sees as vital sea lines of communication that pass through the Strait of Malacca. The plans of the 2000s are now subsumed under President Xi Jinping’s sweeping Belt and Road Initiative, parts of which converge in the Bay of Bengal.

China’s plans aren’t limited to infrastructure. It’s also intensifying security and military cooperation with the littoral states in the bay. China has recently also sold submarines to Thailand, America’s oldest Asian ally, and Bangladesh, India’s close neighbour. Chinese submarines have been making port calls in Sri Lanka, and Beijing is making a play for strategic influence in the critically located Maldives island chain.

India is acutely aware of the underlying strategic implications of new ports and economic corridors running through its continental and maritime neighbourhood. It’s among the few countries that refused to participate in the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in May. On its part, Delhi is scrambling to develop its own plans for regional infrastructure development in the bay.

Having been frustrated at the South Asian regional forum, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, India is trying to revive the two-decades-old organisation called the BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation) to accelerate the integration of the littoral. It has also stepped up recent bilateral efforts with Bangladesh and Sri Lanka to promote infrastructure development in the bay.

India is conscious of its resource limitations and has looked to partner with Japan in the economic development of the Bay of Bengal. Tokyo, which has real experience in promoting regional infrastructure and has strategic reasons to compete with Beijing, has been more than enthusiastic. To strengthen this enterprise, Delhi must also draw in Canberra, which already provides development assistance to the littoral.

Security cooperation, bilateral and plurilateral, has also been an important element of the Indo-Pacific partnership outlined by Modi and Turnbull. Following the first bilateral military exercise in the Bay of Bengal during 2015, the two sides can give it a subregional focus.

As they cope with the unfolding dynamic in the Indo-Pacific in general and the Bay of Bengal in particular, Delhi and Canberra are beginning to see the value of their trilateral engagement with Japan. Modi and Turnbull emphasised third-country cooperation in their joint statement in April. ‘The two Prime Ministers welcomed continued and deepened trilateral cooperation and dialogue among Australia, India and Japan. They agreed to invest in trilateral consultations with third countries to enhance regional and global peace and security.’

At the strategic level, a targeted area for collaboration could be the development of island territories in the Bay of Bengal and the eastern Indian Ocean. India has renewed its commitment to develop the strategically located Andaman and Nicobar islands. While Delhi is hesitant to open up the islands for military collaboration with its partners, the rapidly evolving regional balance will demand that sooner rather than later. Meanwhile, Delhi has begun to consider economic collaborations. Japan has been welcomed to undertake some developmental work in the islands. India must also invite Australia to participate in the economic transformation of this island chain.

Canberra, too, is discussing the development of the Cocos (Keeling) and Christmas islands for strategic purposes in collaboration with its partners, the US, Japan and India. Coordinated development of their island territories could end the tyranny of geography that has limited the strategic cooperation between Delhi and Canberra. Sharing the costs of developing the island facilities and the information generated by them can vastly improve the maritime domain awareness and naval reach of India and Australia.

Delhi and Canberra are also committed to the development of the maritime capabilities of small nations in the Indian Ocean; so are Japan and the US. A joint approach to capacity building could lead to a solid maritime bastion for the four countries in the Bay of Bengal, at the heart of the Indo-Pacific.