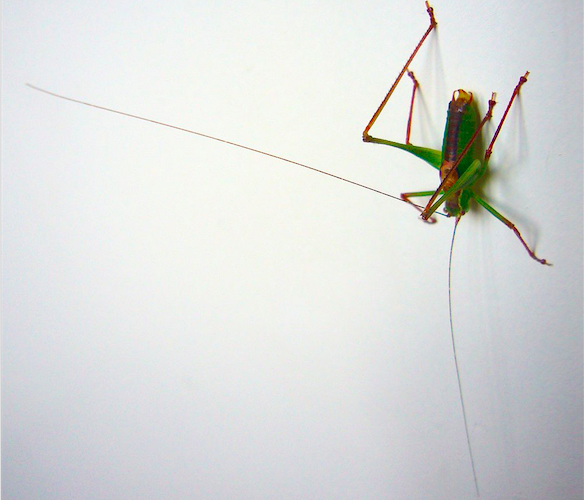

Australia’s strategic antennae are highly sensitive. In recent years those antennae have had many reasons to twitch, chief amongst them being China’s rise and the disruption it’s causing to the region.

Australia’s strategic antennae are highly sensitive. In recent years those antennae have had many reasons to twitch, chief amongst them being China’s rise and the disruption it’s causing to the region.

One of the most telling responses to the region’s changing strategic balances has been the emergence of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept. Scholars and analysts have recognised that the maritime connectivity prompted by globalisation are linking the once-disparate strategic theatres of the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean. As a country that’s tied to both those networks, has an expansive maritime domain and a two-ocean geography, it’s not surprising that the Indo-Pacific conception of Australia’s regional security environment has such appeal.

While the concept has been thoroughly embraced in formal policy documents, it hasn’t been subject to sufficient critical scrutiny. Andrew Phillips’ expansive and carefully argued report is an important corrective to what has thus far been enthusiastic but often superficial advocacy of the Indo-Pacific as a strategic frame of reference. Andrew rightly identifies the concept’s principal analytic weakness: the significant disconnect between the strategic environments of the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean region. But I think that this disconnect requires more than the move from a hyphen to a forward-slash—his ideas are powerful and should become a key point of reference for policy development in Australia and beyond.

Even though it’s an expansive concept, my concern with the idea of the Indo-Pacific is the ultimately partial way in which it responds to the big forces reshaping the region’s security environment. The Indo-/Pacific is a maritime concept, yet the region is being reshaped in both maritime and continental ways. One of the useful components of the Asia–Pacific construct (one that remains the norm in most regional countries in spite of what Indo-Pacific boosters may claim) is the way it linked the maritime with the continental. The Indo-Pacific focuses too much on the maritime and insufficiently on the larger security complex of which it is, most assuredly, a crucial part.

China’s revival is the most important development in world politics of the past 25 years. It’s significant not only because of the explosion of growth, consumption and production, but also because of the way it’s fundamentally restructuring the political economy of Asia and the continent’s strategic geography. Powers like China don’t come along every day, but when they do, they have a gravitational impact on their neighbourhood.

It’s often said that the idea of Asia is a creation of the European imagination. In its origin that may be so, but like the Middle East, ‘Asia’ has become a term embraced by the people of the region. More importantly, because of China it’s becoming an increasingly integrated continent which has economic and security complexes centred around the People’s Republic. And like all significant regions it has different sub-regional elements.

As a synonym for maritime Asia, Indo-Pacific is a perfectly acceptable if somewhat redundant label. My concern with fixing the terminology currently en vogue in Canberra is that we’ll miss the larger trends at work in the region. A case in point is China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative—the biggest and most ambitious plan of Xi Jinping’s foreign policies. At first glance it seems to be cut from the Indo-Pacific cloth. But upon closer inspection, the policy’s most important element isn’t the maritime Silk Road but the overland infrastructure building plans that have multiple ends, one of which is to dilute China’s vulnerability to maritime blockades and choke-points. Fixation on the Indo-Pacific will lead us to overlook China’s crucial Western pivot.

One advantage of the Indo-Pacific concept is that it doesn’t point the finger at China. That allows a useful degree of neutrality in the public debate about strategic geography. Yet the megatrends changing Australia’s international environment are being shaped most profoundly by China. One of the biggest issues confronting Australian strategy is the growing gap that exists between the country’s public diplomacy and its private policy convictions. In public, governments of both hues exude a ‘she’ll be right’ approach with the facile formulation that the country doesn’t have to choose between China and the US. But in private, policy elites acknowledge the profound disruption China is causing. The impulse to the Indo-Pacific formulation reflects an understandable desire to reduce the short-term costs of grappling, both domestically and internationally, with the fact that China is fundamentally changing Australia’s operating environment.

The Australian government must accept that an increasingly Sino-centric regional security order will mean some hard choices for the country. By describing its region as the Indo-Pacific, not only does the government miss the bigger forces at play, but it ultimately shirks that responsibility.