‘Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow’— T.S. Eliot, ‘The Hollow Men’

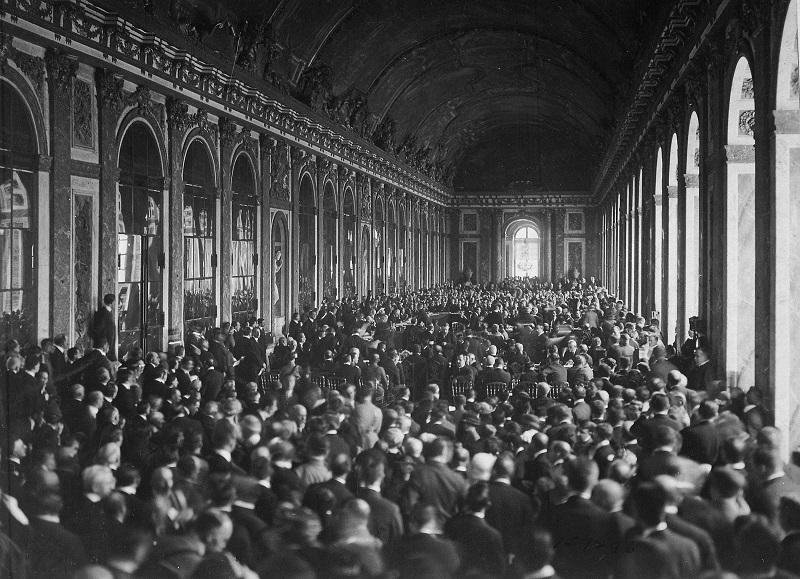

T.S. Eliot offers a raging lament at what the 1919 Treaty of Versailles did to Europe, using references from Heart of darkness to Julius Caesar.

The greatest poem about summit diplomacy—granted, a small category—is a fine lens on the past week: lots of jumping at shadows around the Indo-Pacific, the G20 summit and the meeting between US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping—and then that surprise handshake at the DMZ between Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un.

Step quickly across the century from Versailles to Osaka, and no harsh comparisons, please, about the hollow or solid nature of today’s statesmen and women. Instead, take up Eliot’s insight on the idea–reality gap and what lurks in the darkness.

Any journalist (or historian or diplomat or strategist) considering the words of a leader must track the constant shape-shifting between idea and reality.

The leader seeks to depict existing reality, but equally uses words to describe the reality they’re aiming, building or praying for. The back-and-forth skip from fact to vision can weave from one sentence to the next.

Political art is performed as sleight of tongue.

So in reading or reporting leaders, seek the silences and avoidances where the shadows fall. Call this the Thomas Stearns Eliot rule.

Before heading off to the summit, Scott Morrison delivered the fourth big Asia speech of his prime ministership (the others being on Indonesia, the foreign policy ‘beliefs that guide us’ and ASEAN).

The pre-G20 speech, ‘Where we live’, was all about how wonderful the Indo-Pacific is—and will be—for Australia: ‘an open, inclusive and prosperous Indo-Pacific, consistent with our national interests…where we have our greatest influence and can make the most meaningful impact and contribution. It is the region that will continue to shape our prosperity, security and destiny.’

Morrison listed the ‘great blessings’ the Indo-Pacific offers Oz as the ‘destination for more than three-quarters of our two-way trade’, noting the Australian economy ‘has grown faster than any other advanced economy over the last 28 years’. And so it went for a couple of pages until the prime minister had to address the shadow falling across the idea/reality/motion/act.

Morrison noted that the world’s most important bilateral relationship is strained: ‘The balance between strategic engagement and strategic competition in the US–China relationship has shifted. This was inevitable.’

Inevitable, perhaps. Painful, for sure.

Morrison listed great-power competition, pressures to decouple the Chinese and American economic systems, escalating trade tensions, spreading collateral damage and a global trading system under real pressure. The speech handed all trade blame to China: forced technology transfer, intellectual property theft, industrial subsidies promoting over-production.

Heading for dinner in Osaka with the US president, Morrison’s words obeyed the deeply pragmatic operating directive Australia formulated for dealing with the 45th president since that first explosive phone call shortly after Trump’s inauguration.

The directive states:

Hold tight to what we’ve got, get what we can, and never anger The Donald. Loudly love the alliance. If we mention Trump, it must be warm and joyous. If we can’t say anything nice about Trump because it’s difficult or dangerous or controversial, say nothing. Nothing! Any pokes at US policy must be gentle; prod the US as a national actor while never naming Trump or his administration. Always remind the president Australia has a trade deficit with America; he loves that US-wins-Oz-loses stuff.

As an example of the gentlest of prods, consider this from Morrison: ‘The United States has demonstrated an understanding that the responsibilities of great power are exercised in their restraint, freely subjecting itself to higher order rules, their accommodation of other interests and their benevolence.’

As the directive says, make it gentle and make it general.

US–China trade tensions, Morrison said, should be resolved ‘in the broader context of their special power responsibilities, in a way that is WTO-consistent and does not undermine the interests of other parties, including Australia’. This positive mention of the WTO is brave stuff, according to the operating directive, which advises a Trump-lite call for WTO reform.

Unpleasant surprises still bump around in the shadows. Canberra was appalled by the Bloomberg report, quoting three unnamed sources, on Trump’s private musings about ending the alliance with Japan. After all that intensive schmoozing, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe got this as his G20 present.

The Oz operating directive is based on the Abe playbook for Trump, and love for the alliance is the centrepiece for Japan and Australia. The Bloomberg report was reality gap arriving as reality shock; the denials were embraced if not believed.

Quoting ‘The Hollow Men’ means you can cite one of great concluding couplets of modern poetry:

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but with a whimper.

It’s magnificent poetry but less than convincing reporting. From Versailles to Osaka, leaders can be relied on to talk loud and long. No whimpering allowed, at least in public.

For the rest, the Eliot rule is alive and fresh. Amid the political art of shifting reality, gaps abound and shadows fall.