‘Relations with Indonesia have provided the crucible of modern Australian foreign policy.’ —Bruce Grant, 1972

The great Australian scribe, Bruce Grant, penned that thought about Indonesia–Australia tests and trials in the year of a seminal election for Australia.

Elections are again with us—this time for both Indonesia and Australia. These two most different neighbours now share democracy as well as geography. As ever, the contrasts are far greater than the similarities.

The title of Grant’s 1972 study of Oz foreign policy, The crisis of loyalty, echoes today amid an international bonfire of certainties. And the three-part Indonesia–Australia frame that Grant described still fits.

Precise foreign policy tests: ‘Indonesia has brought home to Australians the concreteness of foreign policy problems … Australia was presented with issues in which it had a specific and acknowledged interest. So there has been a non-proxy, direct and pragmatic flavour about Australian thinking and acting, in official and professional circles, on Indonesia.’

Strategic geography: Indonesia ‘acted as a “locum” for the abstract threats which Australians sensed in their bones. Indonesia gave substance to what has long been called in Australia “the threat from the north”. It brought into focus the vague and undifferentiated fears about “Asians” which Australians have traditionally held. As voyeurs, rather than participants, Australians have nurtured weird ideas about the peoples of Asia … So Indonesia was not only a test of our professionals and decision-makers; it presented an emotional challenge to come to terms with a turbulent and perhaps threatening part of the world.’

The ‘idea’ of Indonesia: The size and potential of Indonesia have intellectual and psychological influence. ‘On the one hand, Australia has learned to respect Indonesian nationalism. It wants Indonesia to be a successful nation, stable and prosperous. Australia has no designs on Indonesian territory and it has no wish to see Indonesia dismembered. On the other hand, Australia does not want Indonesia to become dominant in South-East Asia.’

Remember Grant’s Indonesia–Australia appreciation was penned nearly 50 years ago, near the start of Suharto’s long rule and before Indonesia invaded East Timor. Deep thinking and good writing can have a long shelf life. Australia now is participant, not voyeur, but the rest of Grant’s description is as fresh as today’s election headlines.

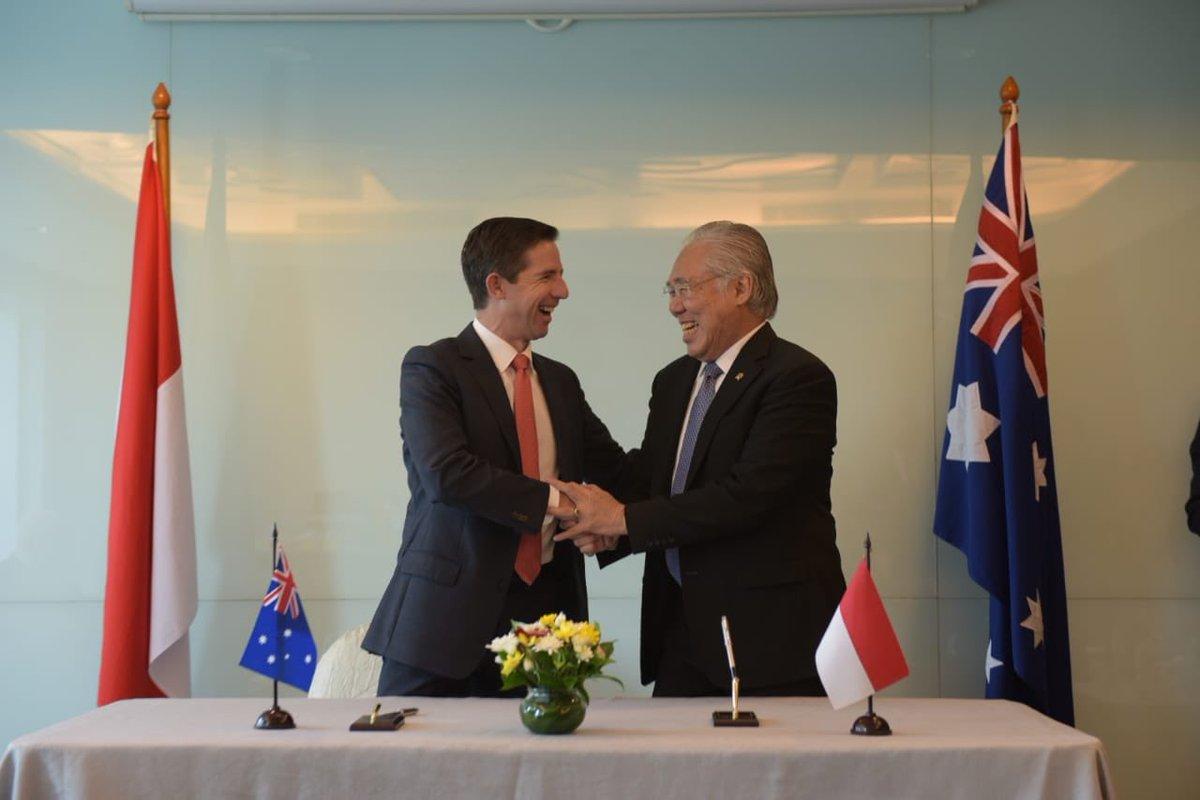

As an example of the next foreign policy test, Australia and Indonesia last month signed a free trade agreement. That deal awaits ratification on the other side of the twin elections.

On the larger and longer term destinies of strategic geography and Indonesia’s potential, consider that this giant neighbour is on track ‘to pass Australia in economic size in the 2020s and eventually in military capabilities by the 2040s’.

The economic/military projection is from Kevin Rudd. In his memoirs, Rudd joins Paul Keating to become the second former prime minister to argue that Australia should join ASEAN, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Rudd follows Keating in stating that the fundamental importance of Indonesia to Australia is at the heart of the argument for Oz membership of ASEAN. (My ASPI paper on why Australia should seek that membership is here.)

Rudd raised the idea of Australia entering ASEAN during his second, short stint as prime minister in 2013, when visiting Indonesia for the annual leaders’ dialogue. He records the response from President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa.

I will always remember SBY and Marty, looking up from their meal, staring at me, smiling broadly, and saying, ‘Pak Kevin, we might be ready for you. I’m not sure that the rest of the ASEANs are ready for you, at least at this stage.’ We all laughed. But there was a method in my madness.

The vision, as Rudd writes, is to multilateralise Australia’s relationship with Indonesia while the neighbours are of similar economic size and no fundamental problems exist.

If by mid-century, the tables were radically reversed in the power relativities between the two countries, and if in the meantime the relationship between Canberra and Jakarta remained entirely bilateralised, the future health of the relationship would depend entirely on the prevailing political dynamics of each country at the time. By contrast, if both countries by then had become members of ASEAN, where bilateral relationships between member states have always been tempered by the collaborative practices, habits and culture of a wider regional institution, it would enhance the long-term stability of the Canberra–Jakarta relationship. There is a continuing complacency in Australia about how the dynamics of the Indonesia relationship will change as Indonesia becomes more powerful in its own right. The time to act in seeking to institutionalise this critical relationship within the wider framework of ASEAN is now.

Australia entering ASEAN would change and enlarge the conception of Southeast Asia. Equally, it’d change and enlarge Australia.

Having Australia and Indonesia as the great twin democracies in ASEAN would give new dimensions to this destined but disparate relationship—still the crucible of modern Oz foreign policy.