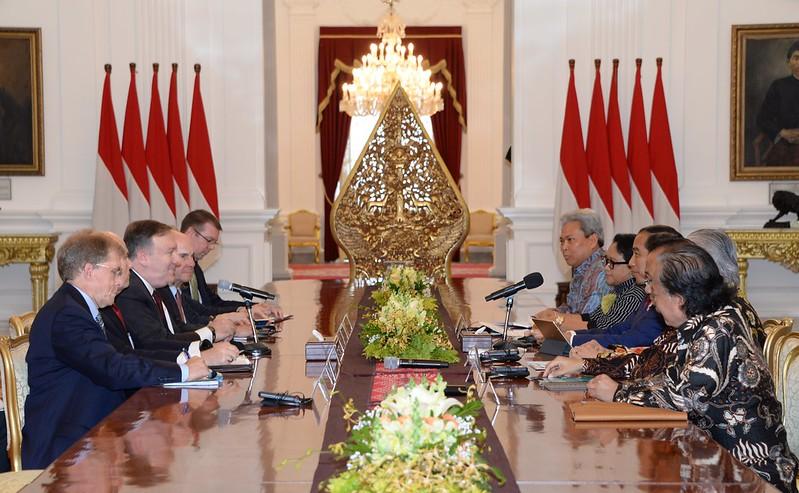

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo is scheduled to visit Jakarta tomorrow to meet with his Indonesian counterpart, Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi. With an itinerary including stops in India, Sri Lanka and the Maldives, it’s clear that the goal of the visit is to persuade Indonesia to align itself more closely to the US-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in confronting security threats from China.

The US has been pulling out all stops to try to persuade Indonesia; witness its willingness to overlook Indonesian Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto’s history of human rights controversies in granting him a visa for a recent visit after more than 20 years in the cold.

From the Indonesian perspective, however, there are several problems with this goal.

First, Indonesia has steadfastly maintained a position of neutrality, fearing it might be dragged into conflicts that it doesn’t want. An independent and active foreign policy, which eschews formal military alliances, is a fundamental part of Indonesia’s strategic culture. Thus, Indonesia flatly rejected a recent US request to host spy planes on the grounds that it would be against Indonesia’s historic position of neutrality, which saw it become one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement. Any deviation from these principles would be bound to cause domestic uproar, something President Joko Widodo can ill afford as he battles to contain the Covid-19 pandemic and resuscitate the economy.

While the Quad bills itself as a dialogue, it is slowly evolving into a mechanism for military cooperation against the perceived threat from China. Even as elements in Indonesian society and the military are willing to consider support for the Quad in the future, at this point the consensus is one of wait and see, and the outcome will depend significantly on whether China increases its aggressiveness in the South China Sea.

Second, Indonesia has growing economic and investment links with China that could be jeopardised by closer alignment with the US. China’s trade boycotts against Australia in response to Canberra’s firm stance on suspected foreign interference and its call for an investigation into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic have been duly noted in Jakarta. While it maintains a huge trade deficit with China, Indonesia can’t afford to pick a fight with Beijing because it needs Chinese investment, especially in infrastructure and heavy industry, to jump-start the economy.

Finally, and most importantly, there’s a question mark over whether the US can be relied upon to continue its favourable approach towards Indonesia. Indonesian military officers are generally apprehensive about the idea of a US president from the Democratic Party, believing that a Democratic administration would put more emphasis on human rights, and be more prepared to intervene in Indonesia’s domestic affairs, in contrast to a business-like Republican Party.

They do not forget that it was the Clinton administration that pressured Indonesia to leave East Timor and imposed a military embargo that wrecked Indonesia’s armament program for years. It was the Republican Bush administration that finally lifted the embargo. To be sure, President Barrack Obama, a Democrat, is seen positively in Indonesia due to his brief childhood connection to the country and his efforts to forge a stronger bilateral relationship as part of his Asia ‘pivot’. But Indonesia’s military didn’t miss the fact that the Arab Spring happened on Obama’s watch, in which they saw the hidden hand of the US meddling in the domestic affairs of Arab states on the pretext of concern for human rights.

In fact, Indonesia’s defence white paper specifically notes that the ‘Arab Spring, political and security upheaval in Egypt, [and] civil wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria’ are examples of major powers waging proxy wars. Not surprisingly, several high-ranking military officers I spoke to said they are hoping President Donald Trump will beat Joe Biden in the 3 November presidential election because that would mean the US would continue to act favourably towards the Indonesian military. A Biden victory might jeopardise that, putting the spotlight back on the question of human rights, especially human rights in the provinces of Papua and West Papua, which remains a touchy issue for Indonesia.

All this will force Indonesia to maintain its hedging game, welcoming the Trump administration’s outreach, but remaining wary of any abrupt change in US policy that might be detrimental to Indonesia’s interest.

It seems very likely that Biden, should he defeat Trump, would want to continue his predecessor’s outreach to Indonesia, considering that there is very strong bipartisan support in the US on the need to take a hard line towards China. Indonesia, of course, will deal with whomever the American people chose to elect. But should Biden wish to court Indonesia’s support, he would need to deal with some historic legacies that have left many here doubtful about the durability of US friendship.