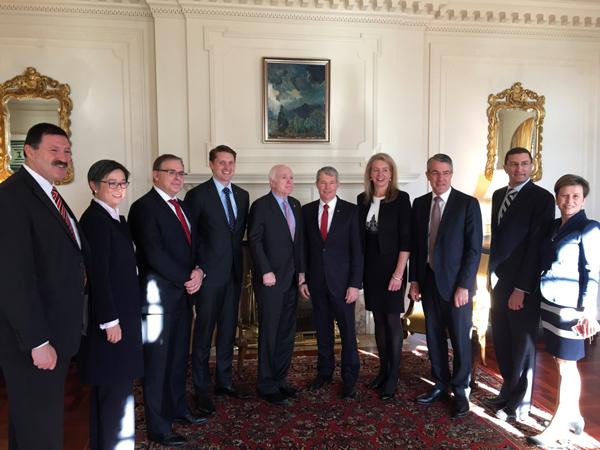

Liberal MP Andrew Hastie’s recent ‘extraordinary’ statement in the Federation Chamber of Parliament under parliamentary privilege prompted a flurry of media reports. Hastie’s speech was remarkable not only because of its content but also because he acknowledged that he became aware of the information after leading a delegation to the US as the chair of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS). Successive reports have described the joint committee as a ‘powerful committee’. But how powerful is the PJCIS really?

The PJCIS was an initiative of the Hawke Labor government in August 1988, stemming from a long history of friction between the intelligence agencies and Labor governments and from deep-seated problems within the agencies. Unlike some, Justice Robert Hope didn’t think a parliamentary committee was needed. In the first Hope royal commission (1974–77), Hope argued that ‘it is not something that appears necessary or appropriate in Australia. But the processes of internal government checks and balances need adapting and re-inforcing.’

While Hope considered the need for a parliamentary committee in his second royal commission (1983–84), he confirmed his previous recommendation that it was neither necessary nor appropriate. He emphasised that it was ultimately a matter for parliament to decide.

In a ministerial statement to the House of Representatives in May 1985, Prime Minister Bob Hawke commented on the usefulness of parliamentary oversight:

[F]urther improvement can be obtained by directly involving the Parliament—on both sides and in both Houses—in imposing the discipline of an external scrutiny of the intelligence and security agencies quite independent of the Executive … [A]ppropriate arrangements can be made to ensure that a small but informed parliamentary committee would operate effectively in the public interest.

While the Hawke government was determined to see the creation of the parliamentary committee, the Liberal opposition was less than enthusiastic. In a statement to the House of Representatives in June 1986, the deputy leader of the Liberals, Neil Anthony Brown QC, said:

We then get into the realms of the utterly ridiculous, the dreamland of the proposed Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation … In addition we will now have a parliamentary committee. We are opposed to that.

Brown’s statement represented the mood in the Liberal Party, which opposed the committee’s creation and promised to abolish it. However, that threat wasn’t carried out when John Howard and the Liberals took government in 1996.

Over the years, the committee has had a number of iterations, from the Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (the ASIO Committee; 1988–2001), to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on ASIO, ASIS and DSD (2002–2005) and, most recently, the PJCIS from 2005.

The PJCIS is constituted under the Intelligence Services Act 2001 and consists of 11 members, five of whom must be senators and six of whom must be members of the House. It has been described as a ‘closed shop’ to crossbenchers. The notable exception was Andrew Wilkie’s inclusion from 2010 to 2013.

The committee’s oversight is limited to overseeing the administration and expenditure of Australian intelligence community (AIC) agencies, addressing matters referred to it by the responsible minister or by a resolution of parliament, and reporting its recommendations to parliament and the responsible minister.

So, while the PJCIS might be powerful in the sense that it can look at the AIC’s administration and expenditure, it is in effect hamstrung, as it can’t review the intelligence-gathering and -assessment priorities of the AIC; nor does it have the power to initiate its own inquiries.

In comparison, similar committees within our Five Eyes counterparts have much wider oversight over their intelligence and security services. They include the UK Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the US House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the newly minted Canadian National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians.

In 2014, Senator John Faulkner wrote a comprehensive report proposing a raft of recommendations for the PJCIS, including a more flexible membership, greater powers and resources, the capacity to generate its own inquiries, better coordination with the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, oversight responsibility for the counterterrorism elements of the Australian Federal Police, and mandatory sunset clauses and review for controversial legislation. In response, in August 2015 opposition Senator Penny Wong introduced the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security Amendment Bill 2015 to change the membership, powers and functions of the PJCIS.

The 2017 Independent Intelligence Review also made a number of recommendations in relation to the PJCIS. Interestingly, a year after that report’s release, it still remains to be seen whether the government will adopt any of its recommendations. However, the review did not recommend expanding the role of the PJCIS to look into the operational activities of the intelligence agencies, to generate its own inquiries or to have greater access to classified reports to bring it into line with best practice in other countries.

Some will assert that Hastie’s use of parliamentary privilege is why parliamentarians, especially members of the PJCIS, shouldn’t be given wider powers to investigate the intelligence agencies. However, the members of the PJCIS and its predecessors have played a critical role in overseeing AIC agencies. Even if the PJCIS is constrained in its power, it’s an important way of maintaining public confidence.

The Australian parliament’s responsibility is clear. As Faulkner observed, ‘Parliament must strike a balance between our security imperatives and our liberties and freedoms. Key to achieving this balance is strong and effective accountability.’

Given the current enhanced powers and resourcing of the AIC and our system of responsible government, there’s no substitute for scrutiny by parliamentarians. It’s time to expand the powers of the PJCIS and finally give it some teeth.