The demonstrations, which began in Iran’s northern city of Mashhad and quickly spread to other cities, were reportedly triggered by a surge in food prices, but they’ve taken on a broader economic and political character with significant domestic and international implications.

The cost of food is only one of number of economic problems affecting Iranians. The public expectation when moderate Hassan Rouhani was elected president in 2013 was a combination of economic improvement and social reforms after eight dark years under his hard-line predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005–2013).

Those expectations were heightened with the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), or nuclear agreement, in 2015. The lifting of most sanctions under the agreement was meant to generate a flow of foreign investment, revitalise old industries and create new ones, create jobs and increase affluence generally. Rouhani was re-elected in 2017 by a clear majority still riding that hope.

But disillusionment has increased. Cuts to food and energy subsidies have added to the country’s already high inflation (about 10% generally, but higher for some basics), high unemployment and underemployment (up to 30%), alleged corruption among the ruling elite and economic mismanagement generally, the cost of military efforts to promote Iran’s influence regionally (especially in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen), lower than expected foreign investment from the JCPOA and doubts about future investment.

Most demonstrators’ focus has been economic. They represent all classes of society, including conservatives and moderates. Their frustrations are directed at the whole government establishment.

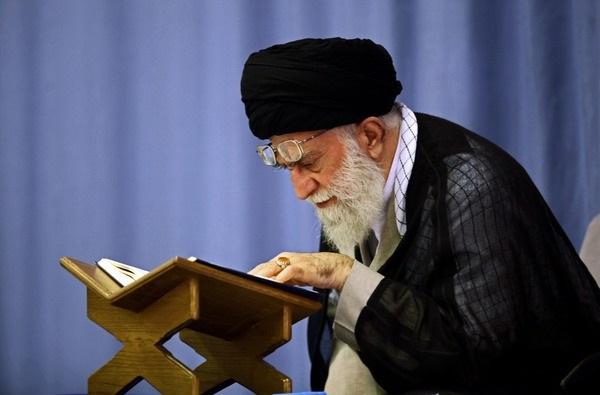

This situation is significantly different from the 2009 demonstrations, when political moderates protested against the allegedly fraudulent re-election of Ahmadinejad. However, there have been attempts by a small minority to exploit circumstances politically, including to protest against the theocratic order of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and to up the ante with violence and vandalism. That led to a crackdown by the police and, in limited cases, by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a force that used brutal suppression tactics in 2009. Elements of social media were shut down to reduce Iranians’ ability to organise demonstrations and to limit any external interference.

More than 20 demonstrators and a number of police were reportedly killed and hundreds of protesters arrested. Khamenei has threatened tougher action if disorder continues. This was a clear warning that more Revolutionary Guard members could be mobilised. The number of demonstrations, and participants, have decreased, but they haven’t stopped. Rouhani has publicly condemned violence and disorder, but defended the right to peaceful protest.

Khamenei and Rouhani don’t want the demonstrations to spread and to threaten Iran’s stability and security. Both will be well aware that the core of the problem is internal; it’s not about ‘external enemies’ as (unconvincingly) alleged by Khamenei, even though external factors are part of both the problem and the solution.

Finding a solution acceptable to all won’t be easy.

The real power rests with Khamenei, who has the support of the conservative clerics and control over the Revolutionary Guard, the security forces and the judiciary. His supporters, through charities and other means, also own or control a significant slice of Iran’s economy. Neither he nor they will readily give up their power and privilege. Khamenei calls the shots in terms of military and other support to regional countries and related Shiite proxies and sets the parameters of foreign policy, including the relationship with the US.

Khamenei is an astute politician, and survivor, and he’s demonstrated a willingness in the past to bend to inevitable forces of change, internally and externally. He may seek to mitigate public dissent, at least for now, by restoring subsidies on basic food and energy, cracking down on the more blatant corruption and deferring some or all of the new funding to clerics. Externally, it’s difficult to see what regional political/military support he’d be willing to reduce, given the degree of national security interests and pride involved.

To achieve much of the domestic agenda, Khamenei needs Rouhani, because of his credibility with key elements of society and the imperative to project ‘unity’ of purpose. Rouhani, supported by Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, is also Iran’s critical interface on broader political and economic issues with the international community, which Khamenei has little direct traction with.

The wildcards are external. Iran desperately needs foreign investment to kickstart the economy, but the keys are largely in US hands. Notwithstanding the positives for Iran during the Obama era, including US and international recognition of Iran’s compliance with the JCPOA, most US sanctions weren’t lifted, and many proposed non-US foreign investments didn’t occur or were put on hold.

Unlike Obama, Trump is openly hostile towards Iran, and he’s threatening to tear up the JCPOA. What deal he’ll try to extract to leave the JCPOA in place remains to be seen. Key elements will be whether Trump can get the support of the other JCPOA signatories and wider European investors for any deal, whether he turns up the screws to further deter foreign (especially European) investment, and whether he demands that Iran cease or limit its support for activities that are ‘destabilising’ the region.

There will be distinct national interest limits to what Iran is willing to cede. If Trump rides roughshod over the Europeans on the JCPOA and foreign investment, seeks to wind back Iranian regional security interests to the direct advantage of US/Israeli/Saudi interests and unacceptably insults Iran, that may mean no deal. Trump needs to heed the lessons of former Iranian president Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005), whose attempt to reach out to Washington and the West was misread and ignored, resulting in an Iranian backlash and the election of Ahmadinejad. Eight dark years followed, and there were no winners.