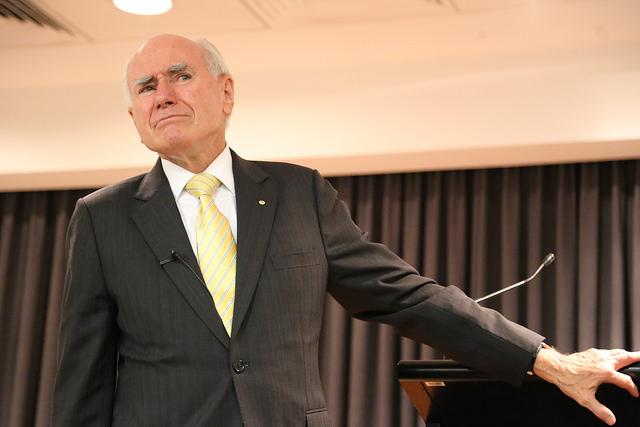

John Howard’s decision to go to war in Iraq was constructed on a fib.

The fib was used repeatedly throughout 2002 and almost to the very start of the invasion in 2003. The fib was that Australia still had an open mind on going to war. The Prime Minister’s fib was that Australia was weighing all the options and had yet to commit to a US-led invasion.

Even at the time it was used, the fib was transparent. In the history of the open secret, the Iraq fib is a fine example.

Use the word ‘fib’ instead of ‘lie.’ This is a political distinction (not to be tried when disciplining children or giving evidence under oath).

The fib in its political garb is designed to conceal or avoid the whole truth. There’s a bit of truth within the fib but the assertion isn’t wholly true. The fib is the politics-as-usual version of ‘being economical with the truth.’ Neither a bent untruth nor a straight lie—many shades of shadiness.

The bit of truth in the fib is that if Saddam Hussein had totally and abjectly surrendered—fully revealed that he had no Weapons of Mass Destruction—Australia would, indeed, embrace the option not to go to war.

Short of that, Australia was all in. And committed. Contemplate the neocon fervour of Bush and the boys in 2002 after the successful invasion of Afghanistan. Saddam’s history and his weak and confused signals of compliance showed how hard it would be to get Washington to take Iraq’s ‘yes’ for an answer. This was a war of choice that the Bush White House embraced. Australia’s embrace was less enthusiastic but it was early and ardent.

Now, examine the fib. We know it was a fib because John Howard tells us so. Howard’s brisk chapter on Iraq in his autobiography makes explicit the lack of any question, or much debate, about Australia joining the US in the war.

Australia didn’t keep its options open. It didn’t even explore the options. No questions asked of the US. No internal questions asked in Australia. Howard is explicit in exposing the fib without regret or repentance.

The book recounts the White House talks in June 2002, where George W Bush understood that Howard ‘would keep my options open until the time when a final decision was needed.’ But the ‘tenor’ of Howard’s comments to Bush meant the US knew it could rely on Australia’s military commitment.

The Australian Defence Force planners working with the US Central Command in Tampa, Florida, through 2002 couldn’t have had too many doubts about Australia’s commitment to the Iraq invasion they were helping to devise.

The ‘tenor’ of that White House deal was a Howard military promise that had already been clearly signalled by Canberra. Open secret, indeed. The pledge wasn’t, however, the story Howard gave Australia all the way to the invasion on 20 March, 2003. For the whole time, Howard told Australia the ‘options open’ version.

The fib was that Australia had the option of stepping back and not joining an American invasion. For Howard, the opt-out option was untenable—almost unthinkable. But the public version was that Australia was thinking hard about the opt-out option. In fact, options were not explored or called for because such work might have produced dangerous negative answers, exposing the fib to dark truths.

In reading Howard’s autobiography, published in 2010, note how the calculations required by that long-gone fib still throb. See this in a characteristic bit of Howard caution in the use of language. Many years of listening to John Howard as prime minister and closely parsing his transcripts can produce a habit of mind that notes what is avoided or redefined as well as what is said.

Thus, Howard writes of the decision to join the US and Britain ‘in the military operation against Saddam Hussein’ or ‘taking out Saddam’s regime’. The word ‘war’ doesn’t appear. Rather than invading Iraq, in the Howard telling the allies decide ‘to go into Iraq.’ By the end of the Iraq chapter, Howard can manage ‘invasion’ a couple of times while still preferring his ‘go into’ formulation, but he can’t use that ‘w’ word.

Whether you prefer to call Howard’s approach a fib, an open secret or politics-as-usual, it had a big impact in Canberra and an influence across Australia.

The fib miasma held the government together, sidelined the public service and provided a fig leaf of cover as Australian public opinion turned decisively against the Iraq war. Next, the effects of the fib…