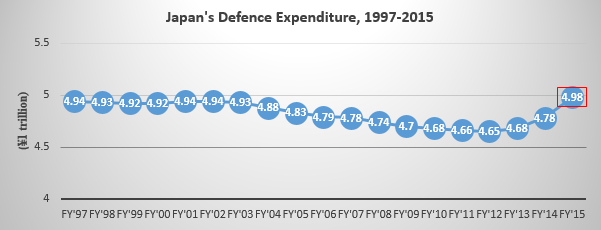

Much has been made in the media (for instance, here and here) about the Japanese government’s ‘record’ defence budget request for Fiscal Year 2015. With ¥4.98 trillion (roughly US$42 billion), it’d be the ‘largest budget ever’, according to a Defence Ministry official. Yet, while such statements imply a shift in Japan’s defence policy, the increase is much less radical and doesn’t indicate a more assertive strategic approach.

True, defence spending is increasing for the third consecutive year, meeting Prime Minister Shinzō Abe’s promise to reverse the decade of declining expenditure.

Figures for FY’97 to FY’14 in Japan Ministry of Defense 2014

But defence spending will remain below 1% of gross domestic product (GDP). And the Abe government’s also increasing spending in other portfolios—it’s requested a record-high general budget of ¥96.34 trillion. So the higher defence spending doesn’t indicate Japan’s ‘remilitarisation’ as has been alleged by some of its neighbours, most notably China. Rather, the increase will allow the Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF) to continue working towards turning into a ‘Dynamic Joint Defense Force’—that is, a more mobile, networked JSDF investing in air-maritime denial capabilities in order to defend Japan’s archipelago whilst increasing interoperability with its US ally.

Consequently, the 2015 defence budget request provides funding for key capabilities already announced in the ‘National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) for FY2014 and beyond’. Big ticket items include the procurement of up to 20 P-1 maritime patrol aircraft; beginning work on a third Atago-class destroyer fitted with the Aegis combat-system for ballistic missile defence; and the acquisition of six additional F-35A Joint Strike Fighters. It also contains funding to enhance the JSDF’s mobility, ISR, and amphibious capabilities. That includes the acquisition of five tilt-rotor V-22 Osprey helicopters (17 planned in total) and the first of three RQ-4 Global Hawk UAVs. The MoD also announced its intention to buy up to 30 AAV-7 assault vehicles (also used by the US Marines) for its emerging amphibious brigade. Further, Japan will continue upgrading its F-15 and F-2 fighters, as well as adding another Sōryū-class submarine to its inventory (including work to improve the propulsion system).

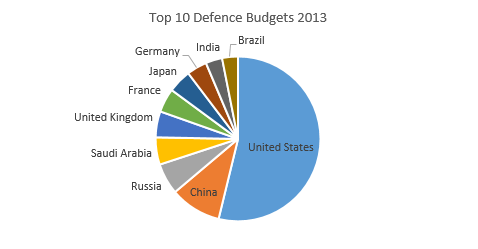

As well, while Japan still spends below 1% of GDP on defence, the total amount has to be seen in comparative perspective. Behind the US, China and Russia, Japan is the fourth largest spender in the Asia–Pacific region, and ranks seventh in the world in 2013 (above powers such as Germany and India).

Source: Military Balance 2014 (paywalled)

Current spending on defence provides Japan with a significant capacity to maintain a modern, high technology force. Indeed, should Tokyo decide to increase its defence spending if the strategic environment deteriorates dramatically to, say, between 1.5% and 2.0% of GDP, it’d quickly climb up the global rankings. And contrary to conventional wisdom, Japan’s enormous government debt of around 240% of GDP isn’t such a problem for the country’s strategic solvency. Japan’s latent capacity to increase defence spending significantly in the future shouldn’t be underestimated.

Yet, at this point such a development is neither desirable nor necessary for Japan. A major defence spending increase would rattle the nerves of its Asian neighbours. The moderate increase in defence expenditure combined with targeted investments in air-sea denial capabilities aims to send a signal that Japan’s military modernisation isn’t about upsetting the regional security order. The goal isn’t to compete with China’s military in terms of platform numbers and spending. Rather, by investing in a smaller, but highly sophisticated JSDF focused on the defence of Japanese islands, the aim is to pose significant challenges to Chinese military planners contemplating offensive operations to seize Japanese islands. Indeed, at present the JSDF would probably be able to defeat such an attempt even without support from the US.

Lastly, while JSDF modernisation strengthens Japan’s leg within its US alliance by improving interoperability and boosting its islands defence capability, it can continue to rely on US’ offensive firepower as a means of deterring foreign aggression. That’s not ‘free-riding’ as often implied but an arrangement that’s in the best interest of both parties, and indeed the region. In the absence of a radical shift in those domestic and external parameters, Japan’s defence spending won’t increase dramatically any time soon.

Benjamin Schreer is a senior analyst at ASPI.