In less than four years, outgoing US President Donald Trump has achieved what, historically, only devastating wars had done: recasting the global order. With his isolationism, wannabe authoritarianism and sheer capriciousness, Trump gleefully took a sledgehammer to the international institutions and multilateral organisations his predecessors had built from the ashes of World War II and maintained ever since. What now?

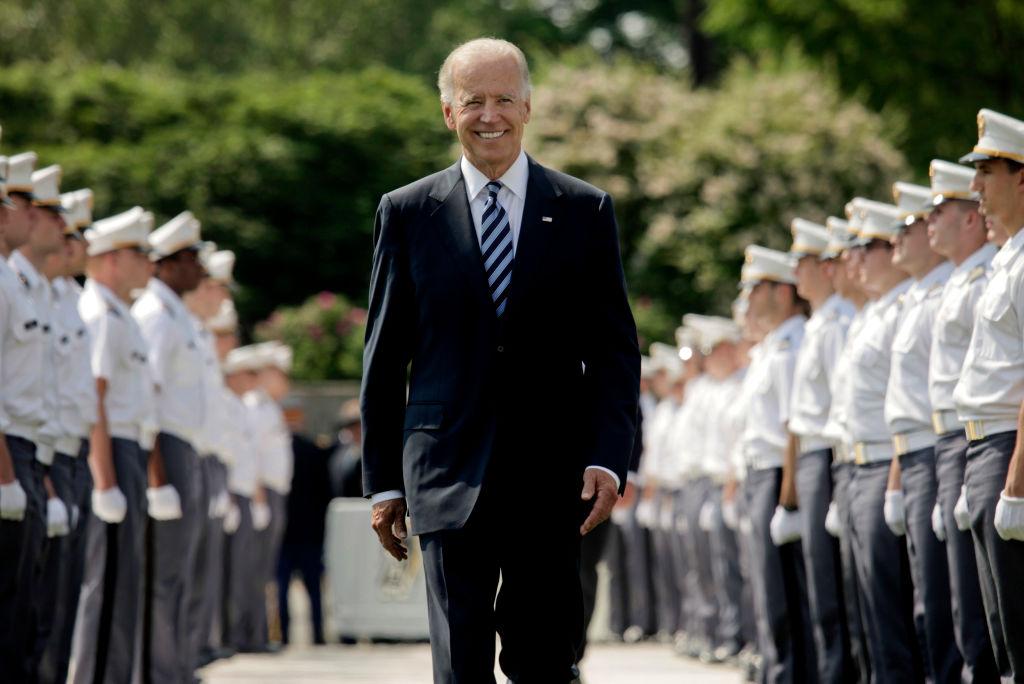

Many hope that, when President-elect Joe Biden takes over, liberal international arrangements can be salvaged, and even renewed. That would certainly be desirable. Unfortunately, it is an unrealistic hope. A post-Trump order appears to be more about a return to the inter-bloc competition of 1945 than to post–Cold War liberal euphoria.

For starters, the Biden administration will be consumed by the daunting tasks of healing the domestic wounds that Trump has inflicted and correcting America’s critical weaknesses, laid bare by the pandemic. The US’s recovery from the most divisive presidency in its history will be neither quick nor painless. Reforming America is a prerequisite to restoring its capacity for global leadership.

Even if Biden’s administration had infinite capacity, there would be no turning back the clock. The status quo ante sprang from a kind of post–Cold War euphoria, animated by the belief that Western liberal democracy had secured a definitive victory over the rest, and the world had reached, in Francis Fukuyama’s famous formulation, ‘the end of history’.

In the 1990s and 2000s, when the United States was the world’s unrivalled economic, military and diplomatic power, the logic of liberal hegemony was compelling. But, in today’s rapidly changing multipolar world, it no longer is. This has been true for more than a decade, which is why the US was retreating from global leadership long before Trump took office.

Although Trump’s isolationism is often portrayed as anomalous, it reflects a strain of American thought stretching back to the country’s founding. Had German submarines not attacked American merchant ships in 1917, the US may well have stayed out of World War I.

Likewise, it was only when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 that the US entered World War II. And after the war, US efforts to preserve peace (by deploying troops) and restore prosperity in Europe (by implementing the Marshall Plan) were driven by fears of Soviet expansion, not some sense of moral duty.

It was also in America’s interest that Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, in whose administration Biden served as vice president, and even George W. Bush before him, took steps to scale back US foreign policy’s hegemonic project. Like Trump, both Obama and Bush voiced frustration about inadequate burden-sharing by America’s NATO allies.

The US retreat from hegemony reflects history that Biden can’t undo: America’s loss of credibility as a result of its long, costly and inconclusive Middle East wars, and the 2008 global financial crisis, which exposed the downside of globalisation and the shortcomings of neoliberal orthodoxy. Far from fulfilling the promise of broadly shared prosperity, it became clear, the free-market ethos of the last few decades had facilitated the emergence of obscene inequalities and the collapse of the middle class.

This combination of never-ending war and rising inequality fuelled the nationalist backlash that propelled Trump to victory in November 2016. The same frustrations were reflected in the United Kingdom’s Brexit vote that June, France’s ‘yellow vest’ protests in 2018, and even the Covid-19 crisis.

A pandemic would seem like an unmissable opportunity for cooperation. Yet it has been met with border closures and competition over supplies and future vaccine doses, not to mention curbs on civil liberties and expansion of surveillance capabilities, including in democracies. Simply put, just when we need global cooperation the most, our broken multilateral system has driven us back to the bosom of the nation-state.

So, the world seems to be returning to a Westphalian order, in which sovereignty prevails over international rules. Trump’s ‘America first’ stance fits neatly within such an order. And while China touts international cooperation in some realms, multilateralism is a fundamentally alien concept to it. It would oppose the revival of a world order based on liberal precepts. Other big nationalist powers (such as Brazil, India, Russia and Turkey) and smaller ones in Eastern Europe (Hungary and Poland) move broadly within the same illiberal realm.

The Biden administration should aspire to lead the world’s democracies in their competition with a rising authoritarian bloc, while upholding the multilateral institutions and structures most essential to peace. To this end, it should immediately abandon the Trump administration’s connivance with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and replace its bellicose strategy towards Iran with an effort to reach a revised, durable nuclear agreement. Fortunately, Biden appears set to do both.

At the same time, the Biden administration will need to treat America’s alliances more as collective enterprises, which the US ideally leads without dominating. From the allies’ side, this shift has already begun, with European leaders, especially French President Emmanuel Macron, increasingly recognising the need to take Europe’s security into their own hands. The US should work with an empowered European Union to contain Russia’s revisionism on NATO’s borders and end its hybrid war on Western democracies.

Similarly, to manage its ongoing strategic confrontation with China, the US will need to work with its Asian allies, such as a rearmed Japan and South Korea. With China having all but abandoned its ‘peaceful rise’ strategy, avoiding violent conflict will be a delicate balancing act.

More broadly, the US will need to galvanise the world’s liberal democracies to forge a bloc capable of standing up to the world’s authoritarians. This should include efforts to counter the forces of disintegration within the EU and, potentially, to transform NATO into a broader security alliance of democracies.

Crucially, the two blocs would also need to cooperate effectively in key areas of shared interest, such as trade, non-proliferation, climate change and global health. This will require diplomatic skills that Trump could scarcely imagine, much less muster.