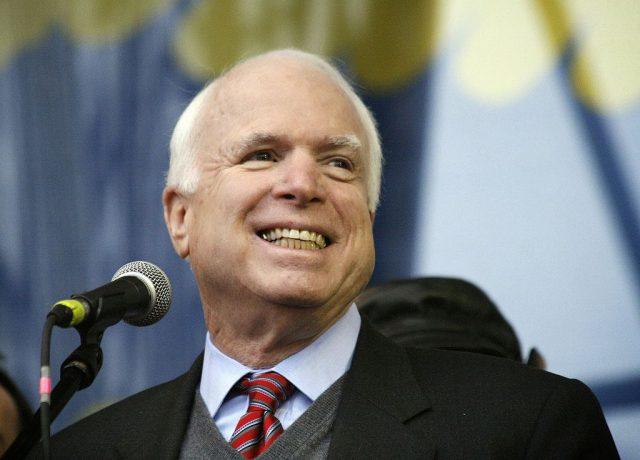

Senator John McCain walked back into the US Senate last week and there wasn’t a dry eye in the place. It was an unexpected event, as all knew of the terrible diagnosis of cancer of the brain, issued following an operation behind his left eye. His return permitted Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell to bring the embattled healthcare legislation to the floor—not that McCain was prepared to vote for it in its current form. In any case, McCain wasn’t back for that. His immediate purpose was a plea for a ‘return to regular order’. In this case, he meant that such legislation shouldn’t be prepared in the Republican backroom but in the relevant committees of the House and Senate. More generally, it was a plea for the Senate to live up to its reputation as the world’s greatest democratic deliberative body, to return to bipartisanship and to its role underpinning the American global stance. McCain asked:

What greater cause could we hope to serve than helping keep America the strong, aspiring, inspirational beacon of liberty and defender of the dignity of all human beings and their right to freedom and equal justice? That is the cause that binds us and is so much more powerful and worthy than the small differences that divide us.

Among Republican leaders he is the ‘anti-Trump’—honest, bipartisan, deeply knowledgeable, courteous and appropriate. It’s strange, then, that what was most on his mind wasn’t just the history and reputation of the Senate. No, it was to shepherd the defence authorisation bill, which contains the increased defence expenditure he has advocated for years—and, ironically, the one thing on which he agrees with Trump. He describes the bill in this manifestation as ‘a product of bipartisan cooperation and trust among members of the Senate’.

Despite his brave words, his colleagues do not expect him to be with them for long. And among them there must be a sense, as Trump speculates on using his pardoning powers for himself, his family and his associates—and as he pressures Attorney General Sessions out of office, probably foreshadowing shutting down the special counsel and his Russia probe—that folk of high standing will need to be around to call the shots on next steps. With his 30 years of Senate service, candidacy for president and extraordinary war record, his leadership would be vital. Many of his colleagues are of his opinion, but not of his stature. No time is good for this illness on a personal basis. It couldn’t be worse timing for his country.

McCain loves Australia, and it is deeply embedded in his mental strategic map. He is in the first instance a man of the Pacific. His grandfather was a prominent commander in the Pacific during World War II. His father commanded submarines operating out of Fremantle in that war, and was then CINCPAC for part of the Vietnam War. At the time, John McCain had been a prisoner of the North Vietnamese for five and a half years. He loved his R and R leave in Sydney as a flier prior to capture.

McCain’s major fault is a foul temper. He was incandescent with rage at what he thought was Trump’s demeaning phone call with the Australian prime minister earlier this year, as he informed the Australian ambassador at the time. He went into greater detail in his Alliance 21 address in Sydney in late May. It contained, beautifully expressed, his longstanding views of the alliance, US and Australian roles in regional and global politics, and the zone’s geopolitics. What was new was an underlying plea throughout that we do our best to influence Trump towards adopting America’s traditional stance.

When I was ambassador, every visiting prime minister, foreign minister, defence minister and their opposition equivalents included McCain on their must-see lists. In his office, heavily decorated with portrait photography by a predecessor Arizona senator, Barry Goldwater, it was an opportunity for cheerful banter. But, more particularly, it was an opportunity for serious discussion about Pacific affairs.

That didn’t mean he was an easy interlocutor. In the US he was forward-leaning on every issue: the South China Sea, the use of Australian bases, engagement in Afghanistan and the broader Middle East. There wasn’t much diplomatic nuance there. The administration never satisfied him; he was out in front not only of them, but also of his party, and probably his electorate. When Obama wanted congressional support for bombing Syria after it crossed his ‘red line’ on chemical weapons, he was one of the few in support. But he had a price—he wanted Syrian opposition bases in the country upgraded and weapons delivered. He was given comfort on that. He wanted direct support by American forces on the ground in Iraq and Syria; not so much was forthcoming. His agenda was as hard for the American government as it was for us.

He understood Australia’s difficulties in its economic relationship with China. But if he wasn’t easy on the US administration, why would he be with us? He calculated Australia as more powerful than we calculate ourselves. Uniquely among American congressional leaders, he understood Australia’s vital role in the South Pacific and he acknowledged that we did the heavy lifting. That’s probably a factor in his calculation of our relative strength.

I once introduced him at a gathering of delegates to the Australian–American leadership dialogue in Washington. It was in a Senate reception room, partly at his invitation. ‘I have just been introduced by the worst ambassador you have sent us’, he said. He thoroughly understood the great Australian habit of ‘taking the piss’. We have had no better friend in Congress.