India’s decision last month to revoke Kashmir’s autonomy and statehood, break it into two union territories and merge them fully with the Indian union caught everyone unawares. The changes give effect to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s vision of India as one nation and one people under one constitution. Indians have reacted with jubilation (majority), concern at the lack of consultation and the military lockdown in Kashmir (many), and criticism of the threat to Kashmir’s cultural identity, especially if India’s sole Muslim-majority state’s demographic balance is altered (minority).

India’s protestations notwithstanding, Kashmir has been internationally recognised as disputed territory. The surprise development might cause immediate diplomatic ructions, but in time the integration of Kashmir will help consolidate the argument that the issue is purely internal. In the military skirmishes with Pakistan in February, the self-defeating neglect of public diplomacy cost India dearly in the global coverage of the competing narratives. Learning from that, the government has decided to engage with the foreign media, but its performance remains amateurish.

From the beginning, Pakistan has taken the initiative on Kashmir and India has had to react. Suddenly Pakistan is in the unaccustomed position of reacting to India’s audacious initiative. A rattled Prime Minister Imran Khan lashed out in an over-the-top tweet on 25 August: ‘India has been captured, as Germany had been captured by Nazis, by a fascist, racist Hindu Supremacist ideology and leadership.’

Muslims comprise more than 14% of Indians and Hindu and Muslim populations increased by 17% and 25%, respectively, between 2001 and 2011. Hindus comprise under 2% of Pakistan’s population, down from around 20% at independence. Indian diplomats have been bafflingly reticent in hammering home this telling statistic every time Pakistan raises the plight of Indian Muslims.

Pakistan has downgraded its diplomatic ties and suspended trade with India, but has met with little success in courting global support. The use of state-sponsored terrorists has become a major liability for Pakistan in polite global society. India’s military is more powerful and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government raised the cost of sub-conventional hybrid warfare significantly by launching retaliatory missile strikes deep inside Pakistan in February. Ironically, writes Ayesha Siddiqa, an expert on Pakistan’s military, India’s actions in Kashmir could help to change the governance balance in Pakistan by underlining the limited military options and the need for civilian-led diplomacy in countering India.

China and Pakistan have extolled their all-weather friendship as ‘higher than the Himalayas, deeper than the deepest ocean, and sweeter than honey’. China took the Kashmir problem to the UN Security Council but failed to get traction from anyone else in the closed-door meeting. Its support for Pakistan was conditioned by caution in not wanting unfavourable attention directed towards its own significantly harsher treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Amid the protracted anti-China protests in Hong Kong, Beijing would also want to retain freedom to act robustly there. So it was content to argue that the mere fact of placing the item on the Security Council’s agenda was proof that the dispute was international and India has obligations to the world community. Its greater potential concern is likely to be Indian military preparations in Ladakh, which borders China directly.

Pakistani-American scholar Adil Najam makes a plausible case for US mediation. President Donald Trump had earlier offered to mediate the Kashmir dispute, but India denied that Modi had requested US arbitration. The imminence of a Pakistan-brokered US–Taliban deal on Afghanistan affected India’s Kashmir calculus. That gives Pakistan leverage in persuading the US to intercede in Kashmir and has raised the prospect of Afghanistan-origin insurgents and arms flooding into Kashmir after America’s withdrawal.

Trump and Modi met on the sidelines of the G7 summit in Biarritz, France. Modi’s presence and Khan’s absence were a telling indicator of the gulf in diplomatic heft. At the joint press conference, Trump said he was good friends with both PMs, that ‘they can manage it themselves’ and that Modi feels he has the Kashmir situation under control.

The foreign ministry of Bangladesh, the third populous Muslim country on the subcontinent, said the matter was ‘an internal issue of India’. Russia washed its hands of the dispute on the same argument. With the Gulf states, ‘Pakistan is likely to interpret neutrality as an implicitly pro-Indian position’. The United Arab Emirates ambassador fully endorsed India’s case, saying the decision would ‘improve social justice and security and confidence of the people in the local governance and will encourage further stability and peace’. On 24 August, Modi received the UAE’s highest civilian award for boosting bilateral relations.

As Kashmir’s indigenous insurgency was captured by Islamists and the call for independence was displaced by the agenda to establish a Sharia-dominated state, the world lost interest in supporting the creation of a semi-independent Islamist enclave at the crossroads of Central and South Asia. The key to a successful Kashmir policy is a successful economic policy that lifts Kashmir’s boat on the tide of India’s prosperity. This is where the Modi government has fallen short. Its policy failures and timidity are now starting to decelerate growth, hurt business and consumer confidence, deter investment and damage job prospects.

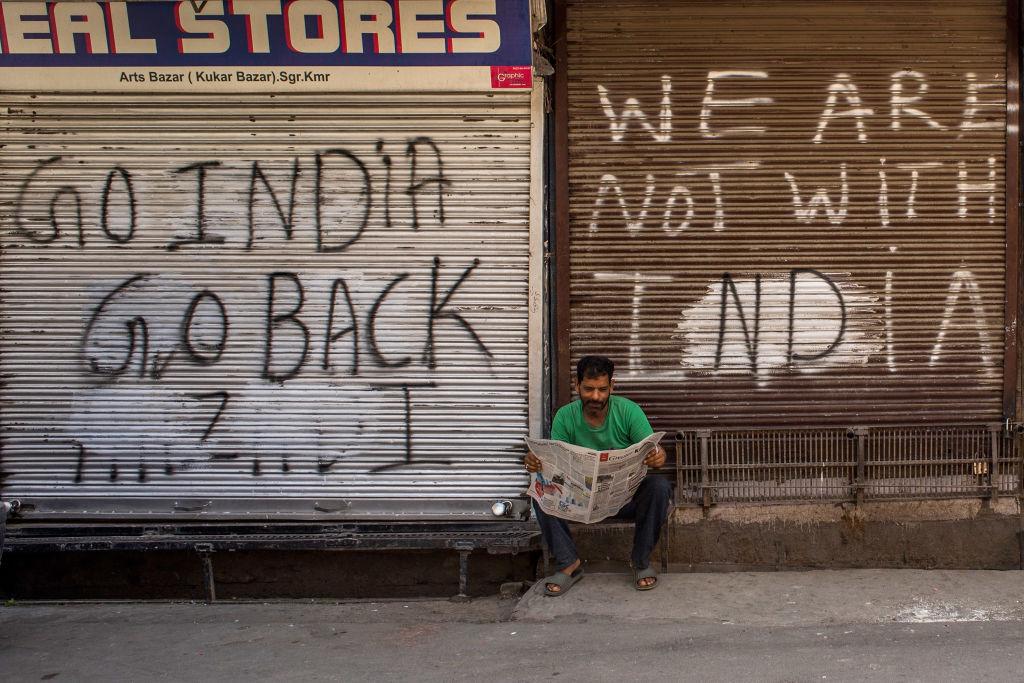

The second potential problem for India is the spectre of mass civilian unrest, resurgent insurgency and Pakistan-sponsored asymmetric warfare that provokes a repressive crackdown, keeps Kashmir on the boil and draws international condemnation. Disaffection and distrust among Kashmiris have been rising alarmingly.

Last year’s report by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on abuses in Kashmir was damning. It noted the effective impunity for deaths, disappearances, sexual offences and other abuses due to various laws that have ‘created structures that obstruct the normal course of law, impede accountability and jeopardize the right to remedy for victims of human rights violations’. The promises of development, investment, jobs and security might placate Kashmiris temporarily, but only delivery on the promises will help to restore normality.

Barring a major unravelling of the internal security situation, world powers will remain preoccupied with major international issues like nuclear threats from North Korea and Iran, the possible collapse of the global nuclear order, Brexit, the China–US trade war, and the Amazon fires and climate change. Few countries will waste political capital in pressuring India on Kashmir.

If India succeeds in stabilising the internal situation, restoring normality and promoting economic growth and development, most countries will accept that Kashmir is an internal matter.