In a previous post, I described how three prime ministers, Gough Whitlam, Malcolm Fraser and Bob Hawke, appointed Robert Marsden Hope to conduct two royal commissions and another inquiry into the intelligence and security agencies in the 1970s and 1980s.

This post discusses the skills, qualities and values that Hope brought to the task.

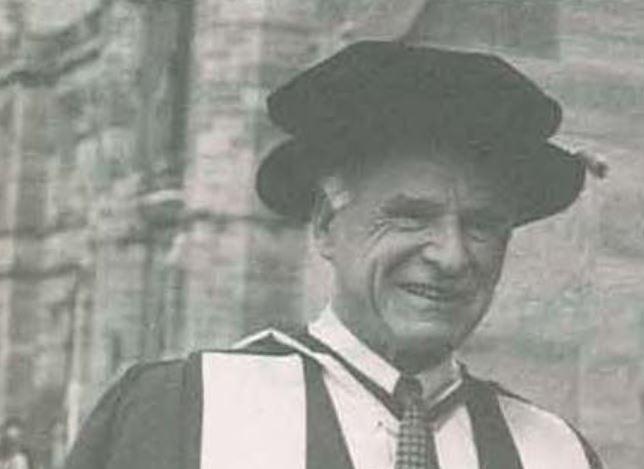

The selection of Hope to conduct the first of the inquiries was one of Whitlam’s wisest appointments. Hope had two sides to his personality, which he himself described as a clash between anarchy and discipline. Most people saw a charming, congenial and collegial man, who won the respect and affection of people of all ages, social backgrounds and political views.

But at times an iron hand emerged from the velvet glove as he expressed sharp disapproval of a barrister, politician or public servant he judged to be incompetent, obstructive or self-serving.

From his childhood, Hope displayed the ability to respect the legitimate demands of established institutions while tolerating, even encouraging, rebels and radicals. He attended Shore School in Sydney, with academic success, but didn’t subscribe to its ‘King and empire’ ethos, absenting himself from the almost-compulsory cadet corps and covering for his sometimes wayward brothers.

Halfway through his law course at Sydney University, Hope enlisted for the Australian Imperial Force and served in both the Middle East and New Guinea, but he declined promotion to any rank higher than corporal.

As a lecturer at the law school, barrister and judge, Hope was regarded as a pre-eminent expert on the complex technicalities of property law and trusts. Away from the bar or bench, he devoted an extraordinary amount of time and energy to cultural, educational and welfare organisations, including theatre companies, an Aboriginal training college and an aged care organisation. His 22 years as foundation chancellor of the University of Wollongong evoked profound respect from all stakeholders, from vice-chancellors to student radicals.

While a senior barrister, Hope was an active member, and for a time president, of the NSW Council for Civil Liberties. Angered by the way in which the NSW police handled anti–Vietnam War and anti-conscription demonstrators, he wrote a pamphlet titled ‘The right of peaceful assembly’, equally critical of undue force by police and violent or illiberal tactics by radical demonstrators. Although normally a Labor voter, he briefly joined the Liberal Party, to secure changes in police regulations. After being appointed to the NSW Supreme Court by a Liberal government, he quickly demonstrated his political independence.

A genuine ‘small l liberal’, Hope earned the respect of both sides of politics, at both state and federal levels, leading to what amounted almost to a second career as an adviser to executive governments. A Liberal government in New South Wales appointed him as chair of an advisory committee on prison reform. This achieved very little, but Hope learned important lessons about inquiries into public policy and policymaking. The Whitlam government then appointed him to chair a committee on ‘the national estate’, whose report led to legislation and administrative structures that embedded in public policy a new outlook on heritage and conservation. Later Hope served for 15 years as the foundation chair of the NSW Heritage Council.

These tasks demonstrated and developed Hope’s skills as an adviser on public policy, most importantly displayed in the inquiries into the intelligence agencies. Whitlam contemplated appointing Hope to the High Court, but instead left him on the NSW Supreme Court, so that he could be appointed (as a serving High Court judge could not) to conduct the national estate inquiry and the intelligence royal commission.

Nearly all of the evidence in the three intelligence inquiries was taken in confidential hearings rather than the quasi-courtroom style seen in television news broadcasts of recent royal commissions. In these hearings, which Hope kept as informal as possible, he was able to deploy his sympathetic charm to encourage information from witnesses who spoke frankly and honestly, sometimes risking their careers, while sternly rebuking those whom he found obstructive or self-serving.

The Combe–Ivanov hearing, which dominated media attention for many months, was the only part of the two royal commissions to be conducted in the quasi-courtroom style. Ironically, this was the format to which this Supreme Court judge was less suited. He was subjected to criticism, often unfair, by civil libertarians and the media, which presented a distorted image of the man and his work.

Although Hope did not study for an arts degree, as he had wished, he devoted considerable time, and a large personal library, to the study of history. He also commissioned a historian to write a history of the Australian agencies before 1945. His approach to his task was based as much on his historical sensibility as on his legal expertise.

These were some of the characteristics of the man whose name is given to the headquarters of the Office of National Intelligence in Canberra. The next posts in this series will discuss the principles underlying the Hope model of intelligence and current challenges to that model.