Investigations of influence operations and information warfare methodologies tend to focus heavily on the use of inauthentic social media activity and websites purpose built to propagate misinformation, disinformation and misleading narratives.

There are, however, a range of other methodologies that bad actors can exploit. One way in which obviously false content can be spread quickly, widely and easily across ‘junk news’ sites is through a syndicated press release.

Here’s a recent example.

Screenshot of press release on AI Organization site, 25 November 2019.

On 29 October, a press release was published on a site belonging to ‘The AI Organization’. The first paragraph says it all [sic]:

This Press Release makes public our Report to the White House and Secret Service in the Spring of 2019, entailing China’s plan to use Micro-Bot’s, cybernetic enhanced dragon flies, and Robo insect drones infused with poison, guided by AI automated drone systems, to kill certain members of congress, world leaders, President Trump and his family. These technologies were extracted from, DARPA, Draper in Boston and Wyss institute at Harvard, who build flying robo-bees for pollination and mosquito drones. It also includes our discoveries of China’s use of AI and Tech companies to build drones, robotics and machines to rule BRI (One Belt, One Road) on the 5G Network.

It should be immediately clear to any human news editor that this press release’s claims—for example, that China is planning to use poison-filled dragonfly drones to assassinate US President Donald Trump and his family—aren’t credible.

This conspiracy theory doesn’t appear to be a case of intentional disinformation. Misinformation and disinformation often make use of the same channels, however, and this example is relevant for both.

On 1 November, the press release was published on a distribution service. It was still available on the distributor’s site as of 3 December.

The distributor describes itself as a company that ‘assists client’s [sic] by disseminating their press release news to online media, print media, journalists and bloggers while also making their press release available for pickup by search engines and of course our very own Media Desk for journalists’.

It also claims that ‘editorial staff … review all press releases before they are distributed to ensure that content is newsworthy, accurate and in an acceptable press release format’.

Evidently, either the editorial staff judged that the AI assassin robo-bees story was newsworthy and accurate, or no review was actually conducted.

The distributor offers different pricing levels for its service. How much you pay determines how many ‘online media partners’ your press release is sent to. For example, the US$49 ‘Visibility Boost’ package includes sending the press release to ‘50+ premium news sites’ as well as syndicating it through RSS and news widget feeds, which the company encourages website owners to embed in their own sites.

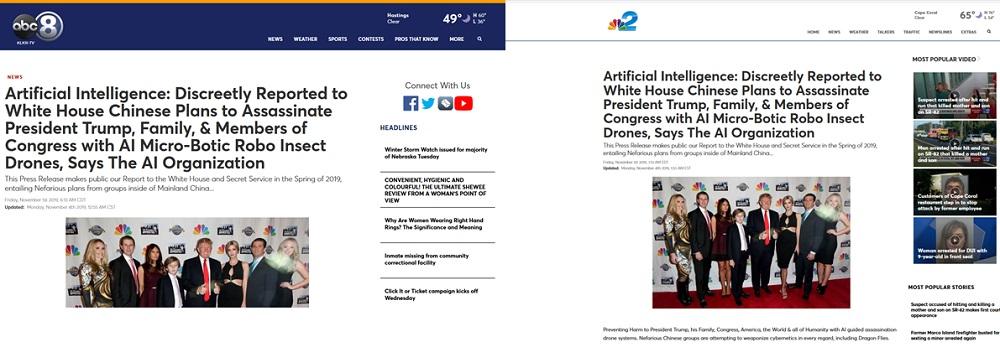

Shortly after it was published to the distributor’s site, the Chinese killer bee press release was running on dozens of ‘junk news’ sites and some legitimate local news sites, including on their homepages, in a format that made it look like political news.

Screenshots of Denver News Journal, ABC8 and NBC2 websites, 25 November 2019.

The main purpose of these sites is likely to be monetisation—they syndicate, buy or plagiarise content to attract readers, and make money by running programmatic advertising.

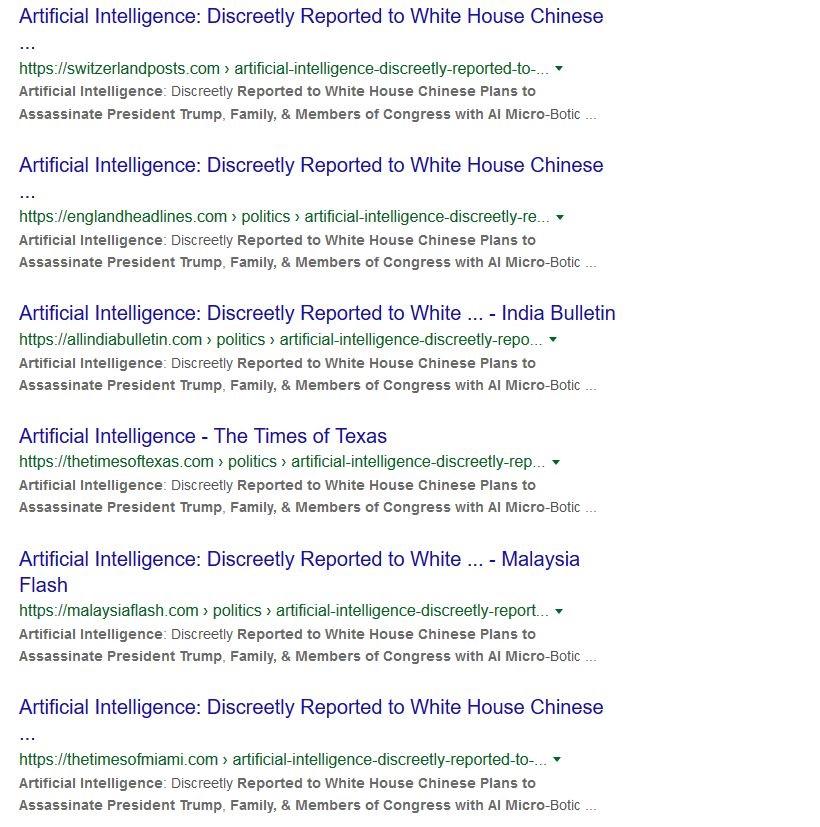

Screenshot of Google search results, 25 November 2019.

As can be seen from the URLs, many of the sites try to position themselves as local news providers—for example, ‘The Times of Texas’, ‘The London News Journal’ and ‘All India Bulletin’. This is at best misleading (the Times of Texas, for example, has an ad encouraging readers to catch a bus from Mumbai for an adventurous family weekend).

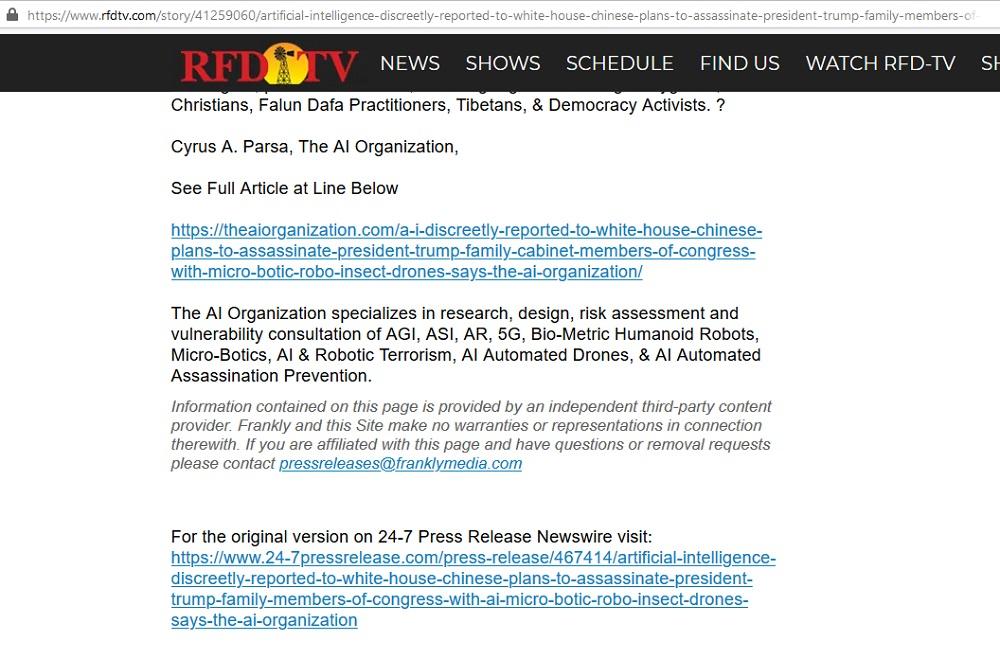

In addition to automated news widgets, the article seems to have been published on some sites through a digital advertising company; the text included below the articles disclaims responsibility for the content even as it’s being distributed.

Screenshot of RFD-TV article including Frankly Media disclaimer, 25 November 2019.

As can be seen in the RFD-TV screenshot, the sites acknowledge in the last line that the article is a press release and provide a link back to the distributor’s post. Many studies have found, however, that the majority of online news readers read only the headline and first few paragraphs of articles. In other words, realistically most readers won’t see the admission that these are not news stories.

Conspiracy theories about weaponised Chinese robo-bees may seem like a bit of a joke, but the underlying system this example highlights is no laughing matter.

Despite being obviously untrue, this piece of content passed through at least three companies and was published across dozens of sites which styled and positioned it in a way that made it appear like legitimate news. This suggests one of two scenarios.

One possibility is that the entire process has been automated, so that no human being—whether from the distributor, the digital advertiser or the operator of the ‘junk news’ sites—is actually aware of the content they’re spreading across the internet. The alternative is that there were people at these companies who saw, or were supposed to have seen, the content, but none of them stepped in to prevent this patently false story from spreading any further. Either scenario is worrying.

The point is not that we should be afraid of the rise of a cult of believers in robo-bee assassins.

It’s that, if content as bizarre and extreme as this can be published and stay published for a month or more, equally untrue but more plausible disinformation could easily make use of the same channels.

In the context of an organised campaign, sowing disinformation across junk news and second-tier news sites would be an effective first step for laundering false facts and narratives into social media and then mainstream media, without the investment or hassle of setting up a new fake news website.

It also has implications for readers attempting to fact-check information online. Imagine, for example, a reader who finds an article titled something like ‘Trump owes millions to Russian oligarch, new evidence shows’. The reader is suspicious and Googles the headline to see whether other media are reporting the same thing. When they see that the same piece appears to have been picked up by dozens of ‘news’ sites, the reader might well think the story is legitimate.

This problem exists for the same fundamental reason as many of the other issues around online disinformation: the business models of these companies depend on publishing content as quickly, widely and cheaply as possible. There’s no significant incentive for them to invest in potentially slow and expensive fact-checking. The only real risk they face for publishing nonsense is reputational—and as this example clearly shows, that’s not enough to stop them.

Fortunately, there is a clear path for resolving or at least mitigating this avenue for disinformation to spread (and potentially help with a few other problems at the same time). Regulatory changes to require companies like digital advertisers and distribution services to take greater responsibility for the content they promote would go a long way towards preventing the spread of untrue information, whether it be misguided fears of AI killer bees from China or something truly malicious.