‘U.S.A. is the slice of a continent … U.S.A. is the world’s greatest river valley fringed with mountains and hills, U.S.A. is a set of bigmouthed officials with too many bank accounts. U.S.A. is a lot of men buried in their uniforms in Arlington Cemetery. U.S.A. is the letters at the end of an address when you are away from home. But mostly U.S.A. is the speech of the people.’ — John Dos Passos

John Dos Passos got some things wrong in his great American novel—U.S.A.—not least that America was ready for political revolution. Outliving that mistake, Dos Passos went from being a Marxist to a Barry Goldwater Republican.

Yet Dos Passos also got big things right in his trilogy, especially the wonderful truth that ‘mostly U.S.A. is the speech of the people’.

Spending the past couple of months in America was to experience again the power and the variety of the many forms of American speech.

To enjoy the special vocabulary and vigour of the Broadway musical, that wonderfully stylised yet infinitely flexible version of American optimism set to song.

To read each day the earnest prose of great American newspapers (praise the Lord, pass the ammunition, and peruse the New York Times and the Washington Post). The first sentence of an American broadsheet yarn can be a four-clause omnibus of piled-on fact. For an Oz hack, used to a lifetime of boiled-down, single-thought 15-word intros, the American hack tradition is ornate oratory. America is so expansive, even its hacks can take a lot of space.

For a political tragic like me, it’s the Washington pilgrimage to the Lincoln Memorial. Marvel at the power of two of the greatest speeches ever delivered, their texts carved on the walls either side of Abe’s statue: the Gettysburg address and the second inaugural. At its finest, rhetoric of the American voice soars.

The American voice can be earnest, slow and deliberate, a counter to the bombastic bile of the current president. And better than Trump, the voice can be smart as well as be sharp: in its stand-up comedy, or rap, or the everyday cheerful wisdom of the guy who drives the bus.

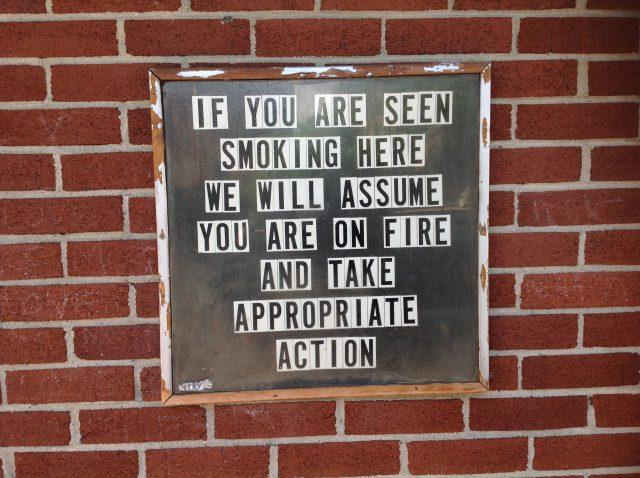

A wonderfully tart example of what I enjoy about American speech was the version of a ‘no smoking’ sign outside a bar in Maine: ‘If you are seen smoking here we will assume you are on fire and take appropriate action’.

And so, to embrace Dos Passos, America can be experienced by the variety of its accents, matching the variety of its people.

The accent assortment is one of the many differences between Australia and America.

The Australian accent goes in a relatively small range from rough to rounded. From Cottesloe to Cairns, from Darwin to Dimboola, it’s hard to pick where an Australian is from merely by the sound of their vowels.

The American accent cartwheels and transforms repeatedly, almost as it crosses state lines. And lots of other elements overlay those regional differences, especially these days the Hispanic influence.

As mentioned in a letter from America last year, an Australian in the US is branded on the tongue—the moment I open my mouth, they know I ain’t from ’round here.

The thought attributed to Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw and Winston Churchill applies to us: America and Australia are two allies separated by a common language.

The separation works in ways both large and small. One of the new, funny elements these days is that Australians feel quite superior about our coffee culture. The Americans sent coffee drinking around the world—now, if they’d only learn to make a good cup! Long prosper the Oz contribution to café world: the flat white.

On the large differences, the former Liberal leader and ambassador to Washington, Andrew Peacock, listed four areas where the national beliefs of Australia and the US differ sharply:

- interpretation of the meaning of political freedom

- the role of religion in public life and the challenge of American exceptionalism

- the place of wealth and economic status in society

- attitudes towards war and the standing of the military.

Michael Evans uses those Peacock points in a fine essay for Quadrant on the different political cultures of the two allies. He adds a fifth: different frontier legacies.

America’s frontier produced the personal liberty, individual energy and spirit of innovation of the land of the free and the home of the brave.

In the Great Southern Land, the harsh bush frontier fostered social equality and collective endurance alongside a talent for improvisation.

Americans distrust government and seek to divide and balance the powers of Washington. Australians are disillusioned with Canberra, not because they want it to do less, but to do more.

A tragic illustration of difference these days is in attitudes to guns and the right to bear arms.

John Howard tells a nice yarn about speaking at the George W. Bush presidential library and being asked about his proudest political achievements. The first two (joining the US in the war on terror and balancing the budget) got loud applause. Then the third on the list: ‘We brought in national gun control laws. The audience went “uuuhhh” … it was like the sound of air exhaling from a balloon.’

From guns to education to health care, the Oz–America contrasts pile. Common languages (just), deeply contrasting cultures. No wonder Australians enjoy the place so.