In the run-up to multiple votes around the world in 2016, including the United Kingdom’s Brexit vote and the United States presidential election, social media companies like Facebook and Twitter systematically served large numbers of voters poor-quality information—indeed, often outright lies—about politics and public policy. Though those companies have been widely criticised, the junk news—sensational stories, conspiracy theories, and other disinformation—flowed on through 2017.

While a growing number of country-specific fact-checking initiatives and some interesting new apps for evaluating junk news have emerged, system-wide, technical solutions do not seem to be on offer from the platforms. So how should we make social media safe for democratic norms?

We know that social media firms are serving up vast amounts of highly polarising content to citizens during referenda, elections and military crises around the world. During the 2016 US presidential election, fake news stories were shared on social media more widely than professionally produced ones, and the distribution of junk news hit its highest point the day before the election.

Other types of highly polarising content from Kremlin-controlled news organisations such as Russia Today and Sputnik, as well as repurposed content from WikiLeaks and hyper-partisan commentary packaged as news, were concentrated in swing states like Michigan and Pennsylvania. Similar patterns occurred in France during the presidential election in April and May, in the UK during the general election in June, and in Germany throughout 2017 as the federal election in September approached.

Around the world, the coordinated effort to use social media as a conduit for junk news has fueled cynicism, increased divisions between citizens and parties, and influenced the broader media agenda. The ‘success’ of these efforts is reflected in the sheer speed with which they have spread.

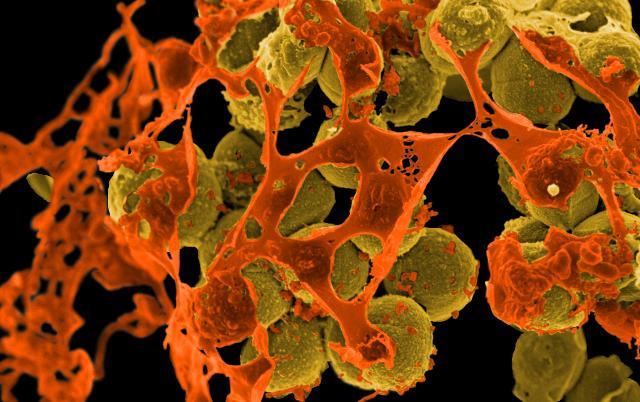

As any epidemiologist knows, the first step towards controlling a communicable disease is to understand how it is transmitted. Junk news is distributed through automation and the proprietary black box algorithms that determine what is and is not relevant news and information. We call this ‘computational propaganda’, because it involves politically motivated lies backed by the global reach and power of social media platforms like Facebook, Google and Twitter.

Throughout the recent elections in the Western democracies, social media firms actively chased ad revenue from political campaigns and distributed content without considering its veracity. Indeed, Facebook, Google and Twitter had staff embedded at Trump’s digital campaign headquarters in San Antonio. Foreign governments and marketing firms in Eastern Europe operated fake Facebook, Google and Twitter accounts, and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on political advertisements that targeted voters with divisive messages.

To understand how pervasive these problems are, we took an in-depth look at computational propaganda in nine countries—Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, Poland, Russia, Taiwan, Ukraine and the United States—and a comparative look at 28 others. We have also analysed the spread of computational propaganda during specific referenda and elections in the last year (and in the past, we have studied Mexico and Venezuela). Globally, the evidence doesn’t bode well for democratic institutions.

One crucial finding is that social media platforms play a significant role in political engagement. Indeed, they are the primary vehicle by which young people develop their political identities. In the world’s democracies, the majority of voters use social media to share political news and information, especially during elections. In countries where only small proportions of the public have regular access to social media, such platforms are still fundamental infrastructure for political conversation among journalists, civil-society leaders, and political elites.

Moreover, social media platforms are actively used to manipulate public opinion, though in diverse ways and on different topics. In authoritarian countries, social media platforms are one of the primary means of preventing popular unrest, especially true during political and security crises.

Almost half of the political conversation over Russian Twitter, for example, is mediated by highly automated accounts. The biggest collections of fake accounts are managed by marketing firms in Poland and Ukraine.

Among democracies, we find that social media platforms are actively used for computational propaganda, either through broad efforts at opinion manipulation or targeted experiments on particular segments of the public. In Brazil, bots had a significant role in shaping public debate ahead of the election of former president Dilma Rousseff, during her impeachment in early 2017, and amid the country’s ongoing constitutional crisis. In every country, we found civil-society groups struggling to protect themselves and respond to active misinformation campaigns.

Facebook says that it will work to combat these information operations, and it has taken some positive steps. It has started to examine how foreign governments use its platform to manipulate voters in democracies. Before the French presidential election last spring, it removed some 30,000 fake accounts. It purged thousands more ahead of the British election in June, and then tens of thousands before last month’s German election.

But firms like Facebook now need to engineer a more fundamental shift from defensive and reactive platform tweaks to more proactive and imaginative ways of supporting democratic cultures. With more critical political moments coming in 2018—Egypt, Brazil and Mexico will all hold general elections, and strategists in the US are already planning for the midterm congressional election in November—such action is urgent.

Let’s assume that authoritarian governments will continue to view social media as a tool for political control. But we should also assume that encouraging civic engagement, fostering electoral participation, and promoting news and information from reputable outlets are crucial to democracy. Ultimately, designing for democracy, in systematic ways, would vindicate the original promise of social media.

Unfortunately, social media companies tend to blame their own user communities for what has gone wrong. Facebook still declines to collaborate with researchers seeking to understand the impact of social media on democracy, and to defer responsibility for fact-checking the content it disseminates.

Social media firms may not be creating this nasty content, but they provide the platforms that have allowed computational propaganda to become one of the most powerful tools currently being used to undermine democracy. If democracy is to survive, today’s social media giants will have to redesign themselves.