MH17 and the limits of Russian power

Posted By Benjamin Schreer on July 23, 2014 @ 06:00

Following Russia’s annexation of the Crimea in March this year, there was plenty of talk about ‘the Bear’s return’ to great power status. Triumphant Russian politicians and media commentators crowed about their country’s return to glory. Internationally, the theme of Russia’s resurgence at the expense of the rules-based, Western order [2] was also common, fuelled by what many regarded as a weak Western response.

But the tragic fate of flight MH17 is only the latest indication of the severe limitations on Russia’s power. In reality, Russia’s return to Cold War-era politics reflects the behaviour of a declining power. Indeed, it’s increasingly obvious that Russia’s short-term gains through its bellicose action in the Ukraine are negated by both immediate and long-term costs.

Domestically, Russia is beset by enormous demographic and economic problems. High-levels of corruption, lack of reform and an overreliance on gas and oil exports have stymied economic growth. In fact, despite having been denounced as too soft, the US’ and Europe’s limited sanctions already have had a serious negative impact on the Russian economy [3]. In the wake of the MH17 disaster, major European powers, including Germany and France, are likely to consider even stronger sanctions. Consequently, as Lawrence Freedman [4] has concluded, ‘Russia’s claims to be a great power are increasingly geo-political rather than geo-economic’.

But Russia’s geopolitical project doesn’t look especially promising either. While nice to have, nuclear weapons and a permanent seat at the UN Security Council aren’t sufficient to circumvent Moscow’s growing international isolation. Moreover, Putin’s dream of restoring the Russian empire, including through an expansionist foreign policy doctrine [5], is likely to go nowhere.

Consider this: to the west, Russia faces a NATO of now 28 members, including many former Warsaw Pact countries. If anything, the annexation of the Crimea has provided new impetus for the alliance [6] to update its force structure, mobilisation scheme and doctrine for operations on its eastern flank. Watch NATO’s upcoming Wales Summit for more to come. The EU also signed an association agreement [7] with the Ukraine (as well as Georgia and Moldova), something it had been reluctant to do so prior to the crisis.

To the east, Russia faces a rising China. Contrary to conventional wisdom, Moscow is well aware about the limitations of its ‘strategic partnership’ with Beijing [8], a partnership increasingly plagued by power disparities in China’s favour. For example, the inability to secure its long land border with China is a serious headache for Russia’s defence planners. Finally, Russia’s southern flank is highly volatile and there’s still uncertainty about the future cohesion of the Russian Federation.

That’s hardly a winning geopolitical design. And, as the shooting-down of MH17 shows, Putin’s proxy war in the Ukraine is becoming more and more a strategic liability. [9] Pressure is growing on him to cooperate in the investigation and to end Russia’s destabilising behaviour in Ukraine.

From an Australian perspective, it’s thus important to recognise that Russia is dealing from a position of relative weakness, not strength. That provides diplomatic opportunities. Russia has already supported this week’s UN Security Council Resolution [10] calling for a ‘full, thorough and independent international investigation’ and bringing those responsible to justice. Behind closed doors, Australia and the international community should also use the momentum to pressure Putin to do his share to bring about a lasting cease-fire in Ukraine as a basis for political negotiations.

But it’s equally important to remember key principles of crisis management: keep communication channels open and refrain from making unacceptable demands. In this context, banning Putin from attending the G20 Summit in Brisbane wouldn’t send the right signal after Moscow’s supporting the UN Security Council Resolution. Further, demands of a return of the Crimea to the Ukraine are unrealistic—no Russian president would survive such a move domestically. Instead, a key objective should be about negotiating special status for those provinces currently under control by the separatists whilst ending Russia’s objections to Ukraine moving closer to the West. It’s unclear whether Russia is prepared to go down that road but such an outcome could mean real progress for the geopolitical mess that is Ukraine today.

Moreover, as the dynamics in the Ukraine crisis could increase the leverage of the West, calls [11] for immediate, even more serious sanctions should be resisted unless the Russian government fails to follow through on its pledge to punish those accountable or if Moscow continues to destabilise Ukraine. While some defence-industrial steps make sense (for example, France would be well-advised to cancel the sale of two Mistral-class amphibious assault ships [12]), further economic sanctions could lead only to a weaker Russia acting even more erratically. The isolation and humiliation of wounded powers has never been a good strategy in international relations. And whether we like it or not, we still have to find ways to work productively with Russia. It may not soon be the great power [13] it was in the Cold War, but it will still be able to cause serious problems in its near abroad and elsewhere.

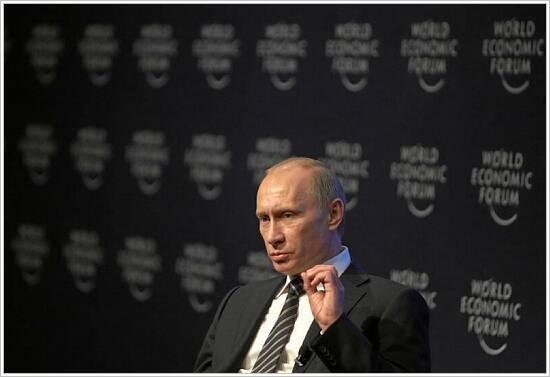

Benjamin Schreer is a senior analyst at ASPI. Image courtesy of Flickr user World Economic Forum [14].

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /mh17-and-the-limits-of-russian-power/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: https://aspistrategist.ru/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/3238714378_3dfa48a3c2_o.jpg

[2] theme of Russia’s resurgence at the expense of the rules-based, Western order: http://thediplomat.com/2014/03/why-did-brics-back-russia-on-crimea/

[3] Europe’s limited sanctions already have had a serious negative impact on the Russian economy: http://www.newsweek.com/2014/07/25/putin-won-crimea-hes-about-pay-price-259064.html

[4] Lawrence Freedman: http://warontherocks.com/2014/03/ukraine-and-the-art-of-crisis-management/

[5] expansionist foreign policy doctrine: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/20/opinion/sunday/protecting-russians-in-ukraine-has-deadly-consequences.html?_r=0

[6] new impetus for the alliance: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43478.pdf

[7] The EU also signed an association agreement: http://online.wsj.com/articles/eu-signs-pacts-with-ukraine-georgia-moldova-1403856293

[8] limitations of its ‘strategic partnership’ with Beijing: http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303480304579577570487443000

[9] proxy war in the Ukraine is becoming more and more a strategic liability.: http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/07/vladimir-putin-russia-proxy-war-ukraine-crimea-109074.html

[10] UN Security Council Resolution: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=48318#.U83DAvmSyao

[11] calls: http://www.commentarymagazine.com/2014/07/18/russias-provocation-demands-tougher-action/

[12] France would be well-advised to cancel the sale of two Mistral-class amphibious assault ships: http://thediplomat.com/2014/07/after-mh17-france-must-cancel-sale-of-warships-to-russia/

[13] may not soon be the great power: http://carnegie.ru/eurasiaoutlook/?fa=56201

[14] World Economic Forum: https://www.flickr.com/photos/worldeconomicforum/3238714378

Click here to print.