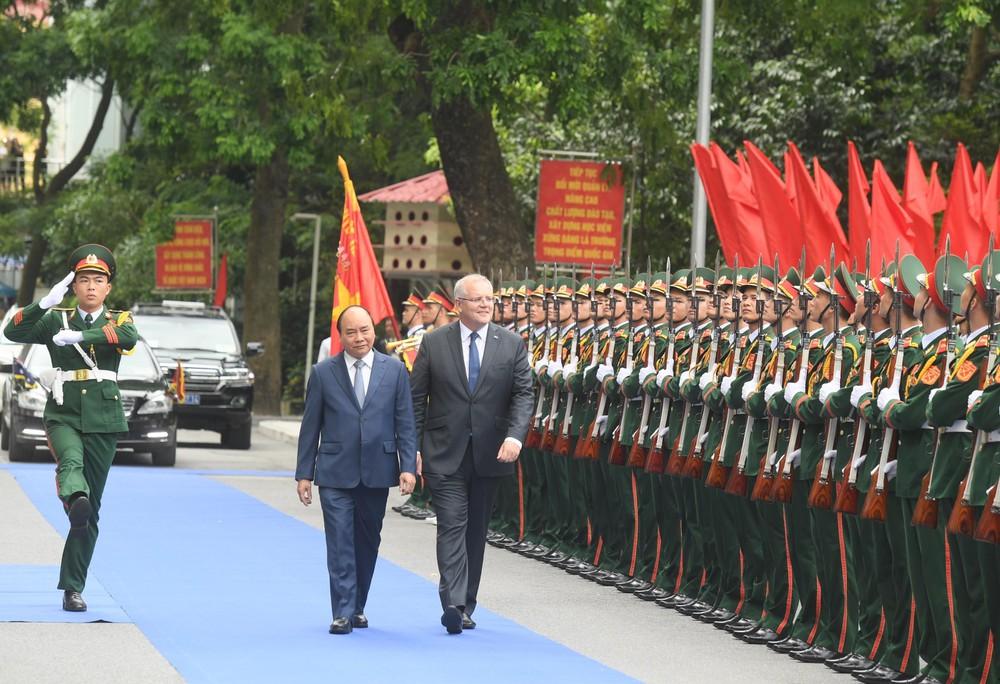

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has just completed an official visit to Vietnam—a strategic partner and a priority country for Australia’s regional relations. Indeed, bilateral relations have been going from strength to strength and are likely to continue to broaden and prosper.

The visit resulted in commitments to bolster economic ties as well as support for the multilateral trading system and working towards completing the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. People-to-people ties will be boosted by expanding Australia’s work and holiday visa quota for Vietnamese nationals from 200 to 1,500 per year.

The two countries also committed to strengthening collaboration in knowledge and innovation and leadership training by establishing a Vietnam–Australia centre at the Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics in Hanoi. Morrison visited the mobile field hospital that will soon form part of Vietnam’s continuing contribution to the UN peacekeeping mission in South Sudan. Australia has been playing a key supportive role in Hanoi’s contribution there, a highlight in recent bilateral ties.

Reviewing their strategic partnership, Hanoi and Canberra agreed on a plan of action for the period 2020–2023 that will focus on three priority areas: enhancing economic engagement; deepening strategic, defence and security cooperation; and building knowledge and innovation partnerships.

These are all very positive developments and welcomed on both sides.

But the timing of Morrison’s visit put the spotlight on another issue—one that goes beyond just bilateral relations.

The Chinese survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 and its maritime militia and coastguard escorts have been a fixture in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone around the Vanguard Bank in the South China Sea since early July. The survey ship briefly left the area and then returned, moving even closer to Vietnam’s shores. The US State Department issued a second statement following the return of the vessel, explicitly condemning China’s actions and supporting Vietnam’s longstanding oil and gas extraction and exploration activities in the area.

The gravity of the incident hasn’t been fully appreciated around the world, and Hanoi has been hoping for more diplomatic support from the international community.

Prior to Morrison’s visit, Foreign Minister Marise Payne signed a joint statement of the Australia–Japan–US strategic dialogue with her counterparts Mike Pompeo and Taro Kono, and the issue was also mentioned in the joint statement from the AUSMIN meeting earlier this month in Sydney. In both statements the parties expressed concern over disruptive activities in relation to longstanding oil and gas projects in the South China Sea. But Vietnam hoped for stronger language from Australia during Morrison’s visit.

While land reclamation and militarisation, freedom of navigation, and even the future of the ASEAN-developed code of conduct were discussed during the visit, Morrison avoided naming the incident around the Vanguard Bank and calling out Beijing’s actions. At a press conference in Hanoi he was asked explicitly about the need to do so, but referred to principles of international law instead.

Morrison declined to take sides and instead drew a vision of an Indo-Pacific where sovereignty and independence are respected and no country suffers from coercion from another. When pressed to specify exactly what type of coercion he was referring to, the prime minister defined it as ‘any impingement on their own sovereignty and independence that would prevent them in any way from pursuing lawfully what is their objective’.

Morrison’s careful tiptoeing around the issue is not out of step with the inclination of other ASEAN states, for example, which feel frequent pressure from Beijing not to speak up about South China Sea matters. It was a deliberate effort not to name China, which seems odd given both the timing of the trip and Australia’s vocal defence of the rules-based order. For this first official bilateral visit from a sitting Australian prime minister to Vietnam in 25 years, Morrison’s performance was rather underwhelming.

Besides the carefully worded official statements, the visit served the purpose of encouraging Hanoi to continue to stand up to China. Morrison is right in recognising Vietnam’s strategic importance and is right not to make the visit about China only. But while stressing the upgrading of the relationship from one of ‘friends’ to ‘mates’, his reticence may also be signalling that his government will be even more hesitant to call out China over its activities in the South China Sea.

The Haiyang Dizhi 8’s incursion into Vietnam’s EEZ has international ramifications. This isn’t an incident that has happened in isolation, and a muted international response will only reinforce what Beijing is looking for—a gradual but consistent normalisation of its actions that helps it achieve control of the South China Sea. In fact, the level of Beijing’s activities in the area has been abnormally high in recent times. Along with the Vanguard Bank situation, there have been missile tests, military exercises, warships sent to the Philippines, survey vessel activity, and frequent harassment of fishermen throughout the region.

While smart diplomacy requires Canberra to carefully consider its statements as its voice becomes more consequential in the era of tense great-power competition, it also needs to work out a balance between speaking out and deftly side-stepping difficult issues. Effective diplomacy includes speaking up when necessary.