It’s notable that Prime Minister Scott Morrison allocated an additional job to himself in announcing his second ministry last Sunday. This was to make himself minister for the public service. Greg Hunt is named in the new ministry list as ‘Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for the Public Service and Cabinet’—in effect the cabinet secretary. Previously, Finance Minister Mathias Cormann had been dual-hatted for several years as minister for the public service, and before that Eric Abetz had been minister assisting the prime minister for the public service during Tony Abbott’s prime ministership.

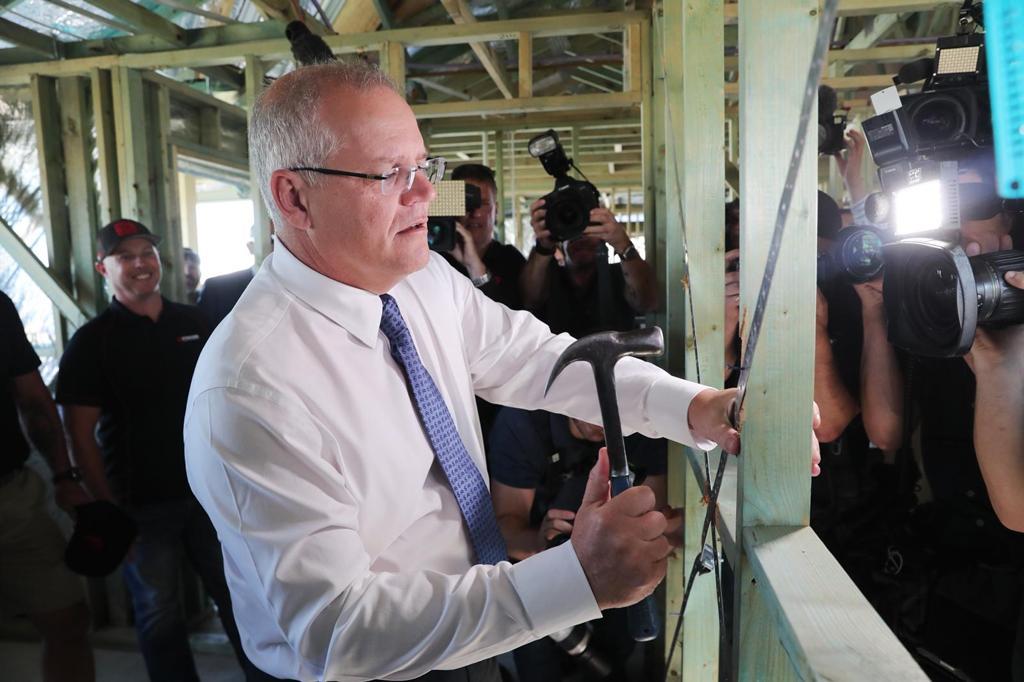

What’s in a name? Quite a lot when it comes to a prime minister signalling a reformist intent to shape the Australian public service (APS). Let’s be clear: Morrison didn’t have to take on this role. A prime minister’s day is already full enough without additional responsibilities. Strong PMs can also choose to reach over the shoulders of ministers to shape any policy area, but direct day-to-day steerage is a different thing. Morrison’s conscious decision to keep his hands on the APS ‘engine room’ of policy capability (and to appoint Hunt to assist him with that) is a significant fact that will have Canberra’s agency heads paying close attention.

What might Morrison’s interest be in the APS—an institution in a territory not naturally thought to be the Coalition’s heartland? Could it be that he understands as John Howard did that the road to policy success for any government runs through the land of the APS? Get the relationship right—which means a respectful and creative interaction around policy—and both government and the APS do well. On the other hand, prime ministers and ministers who develop poor interactions with the public service often find themselves cut apart when the pink batts hit the fan.

So what does Scott Morrison want from the APS? He lost no time getting the department and agency heads together just days after the election—itself a significant and symbolic act—and setting out his expectations. This is how the PM described it to 2GB’s Alan Jones:

I had all the public servants together yesterday in Canberra and told them a couple of important things. One is, their job is not just to do the big things well, but do the little things well, the things that people rely on; returning the phone calls, making sure their services are being delivered, making sure the payments turn up on time.

Jones: Good on you.

Prime minister: All of those sorts of things, but when it comes to the big things it’s about getting these big projects actually happening. I told you and I talked a lot in the campaign about congestion-busting infrastructure. I want a bit of bureaucracy congestion-busting too when it comes to getting a lot of these things going. That’s important for investors who want to invest in Australia and its future, but it’s also important to get these projects delivered on the ground, whether it’s the National Water Grid or whether it’s the East–West Link or whether it’s the Rail Link out there into the Western Sydney Airport.

All of this is important. I’m just keen to get off on the right foot and make sure that these things are being delivered on the ground.

‘Bureaucracy congestion-busting’ suggests some impatience with the public service’s ability to shape imaginative policy agendas quickly. Morrison would hardly be alone in coming to that view. In my recollection, prime ministers Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard and Abbott all expressed some frustration about not receiving imaginative policy thinking from the APS.

Morrison was also reported in the Canberra Times as saying to the public service heads that there would be a need for more policy effort in regional security:

I think it very important that we continue to focus on the ways we can use our influence and our relationships and build on those relationships in the Indo-Pacific region and with our friends and partners around the world to continue to be a voice of reason and common sense that is focused on the prosperity and the peacefulness in our region for the people of our region.

In his short time as prime minister before the election, it’s clear that Morrison saw a need and an opportunity to lift Australia’s diplomatic, economic and security effort with the Pacific island countries, which ultimately led to the announcement of a PNG–Australia and possibly US naval facility on Manus Island. Under an earlier PM, that Manus outcome might have been described as a ‘captain’s pick’; my understanding is that the idea didn’t surface from within the APS.

In my view it was exactly the right call. We elect the ‘captains’ to make the smart policy choices, after all. But it’s rather embarrassing that, after months of pushing the national security community to come up with lateral thinking on increasing engagement with our Pacific island neighbours, the policy cupboard looked distressingly bare for a government that was demanding more.

So the APS is subtly on notice to do a better job of developing innovative policy thinking for a prime minister wanting to make a mark on the international stage and looking for new ways to do that. The ‘Pacific step-up’ will clearly be a central part of the agenda, but there’s just as much need to do the same for Australia’s relations with Southeast Asia, and especially with Indonesia, where a freshly re-elected Joko Widodo government will be looking for a new start in relations with Canberra; with Europe, including with the UK as it limps on with the sucking wound that is Brexit; and with India, in our bilateral relationship that never quite delivers. Most importantly, Morrison needs to find smarter public language about dealing with China—so as not to be stuck in the supposed bipartisan consensus about Beijing which maintains that if we do and say nothing all will be right with the world.

And sooner rather than later Morrison will meet Donald Trump. The US president is an unusual collection of quirks, but increasingly in control of the administration with few adults left to curb his worst instincts. Trump’s recent reference to Australia’s walk-on role in the Mueller inquiry (Alexander Downer’s lubricated meeting with George Papadopoulos at a London wine bar in 2016) could be a niggle in the relationship if Morrison doesn’t shift the discussion onto more positive territory—like getting the government policy and regulatory settings right to supercharge private-sector investments in each other’s infrastructure and science and technology sectors: great for our economies and for our security.

Governments send the APS demand signals for what they want on the policy menu. Morrison’s decision to put himself directly in charge of the public service is as clear a signal as he could send about his interest in seeing more innovative policy offerings—and better delivery of the programs flowing from those policies—from an institution that hasn’t been pressed hard on policy creativity in quite some time. Morrison’s Cabinet colleagues will also reflect that the weight will be on them to deliver to this agenda as well.