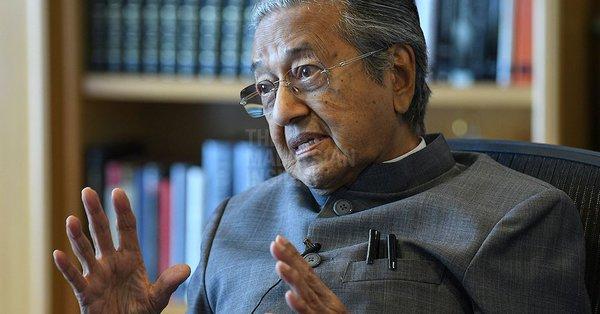

Mahathir Mohamad thinks Australia might earn the right to join ASEAN. Indeed, Dr M. thinks Australia could be ‘entitled’ to ASEAN membership. Pause for a moment of amazement.

This is Dr Mahathir, the Malaysian leader who delighted in throwing bombs and barbs at Oz—most famously the ‘recalcitrant’ row with Paul Keating over APEC, a previous reimagining of Asia’s region.

Campaigning to overthrow much of what he created in Malaysian politics, the 92-year-old is throwing lots overboard. Why not some of his old distaste for Australia?

Mahathir always argued that Australia didn’t belong in Asia. His line was that Australia was more interested in its Brit heritage and US alliance than in its Asian future. Dr M.’s traditional taunts still tease, but now with a positive twist in the tail.

In his interview with Jamese Massola, Mahathir argued that Australia would have to prove itself more ‘Asian than European’ to join ASEAN. So far, so familiar. The shift, though, is Mahathir’s acknowledgement of a different Oz. ‘There are now more liberal attitudes by Australia,’ Mahathir said. ‘In the past of course, it was White Australia, but currently they admit people of other ethnic groups.’

In the future, if Asians and Africans were treated as well in Australia as ‘white’ Australians, Mahathir said, and ‘if they understand the priorities of East Asia, then I think they are entitled to join ASEAN’.

As an endorsement of Australia joining ASEAN, Mahathir runs the gamut from tongue in cheek to lukewarm. Still, it’s a notable echo of Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s comment that Australia joining ASEAN is a ‘good idea’. That Jokowi and Mahathir will nod towards the idea is a long way from saying its time has come—more that it’s timely to start thinking and talking about what it would mean for Australia and ASEAN.

The argument I’ve been mounting for Australia to join the ASEAN Community describes a long process reaching out over the horizon. Still, the event horizon around here has been shifting fast as lots of nostrums fall into geopolitical black holes.

Jokowi’s surprising expression of support ahead of the ASEAN–Australia summit in Sydney produced a polite response of pleasure from the Australian government—plus lots of arguments from many others about why Oz membership can’t happen. These unenthusiastic/dismissive responses will frame the Oz–ASEAN discussion. So let’s group the negatives and offer responses.

Not on the map: The geographic argument is that ASEAN is solely about Southeast Asia—Australia isn’t on that map. Well, Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea are already part members of ASEAN. And ASEAN is stretching its geographic understanding, especially with the East Asia Summit. The idea of a new form of membership—Australia and New Zealand joining as ASEAN Community partners—is a means to sidestep geographic prescriptions.

Abandon our principles: Australia would have to sit down and shut up to join the club. This is tosh—a cautious counsel of engagement, not commitment. We should have more confidence in the strength and worth of Australia. And dismiss the strange argument that it’s safer for Australia to stand outside and shout about our beliefs, not go inside and argue for them.

One of the best lines on this was uttered more than 25 years ago by the distinguished historian of the Chinese diaspora, Wang Gungwu, who did Australia the honour of becoming an Australian citizen. Wang observed that Australia’s liberal history gives it something special to contribute to the region:

Paradoxically, what Australians value about their culture: the law, the respect for human rights, the parliamentary system, which are not features of Asian societies, are what attract Asians.

ASEAN would say ‘no’: Jokowi offers a ‘maybe’ answer to that ‘no’ assumption. The Indonesian president’s ‘maybe’ responds to the challenges confronting ASEAN and what Australia could offer. Australia would join the act of creation that is the ASEAN Community, not Suharto’s old ASEAN.

The Southeast Asian future Australia wants is the one ASEAN proclaimed for itself in 2015 with the creation of its Community. The Community principles, expressed in three strands—political-security, economic and socio-cultural—comprise a vision that Australia, as a liberal democracy, can embrace, endorse and enlist for.

China’s veto: ASEAN’s consensus principle means that if any of the 10 members says ‘no’, that would block Oz membership. China’s hold over Cambodia and Laos would ensure the veto.

China wasn’t able to bar Australia from joining ASEAN’s East Asia Summit. And China’s grip has been known to slip, as it did when Myanmar rebelled against Beijing’s suzerainty at the start of this decade. The tighter China grips ASEAN, the more it forces the association to ponder both symbolic and substantive moments of resistance.

Identity: ASEAN manages to express a regional identity based on a series of strong and deeply different national identities. That extraordinary achievement is part of the ASEAN miracle. Once, Australia failed the identity test—today it doesn’t.

Even Dr Mahathir sees the multicultural nation that Australia has created. Dr M. grasps the reality of what George Megalogenis calls the ‘epic transformation’ of Australia’s population from white Anglo-European to Eurasian.

Australia has crossed the population diversity threshold: we are a Eurasian society, with migration from China and India driving the change. Australia must build a Eurasian foreign policy that serves the new identity in our streets.

Jokowi and Dr M. haven’t offered Australia an invitation or a plan. Yet they have noted that Australia has changed, just as the times are changing fast for ASEAN. ASEAN can’t merely rely on the old structures and well-tested habits to muddle through. Neither can we. That’s the basis for a great conversation about our shared future. The discussion—both aspiration and insurance—is about where we might be in five to 10 years from now.