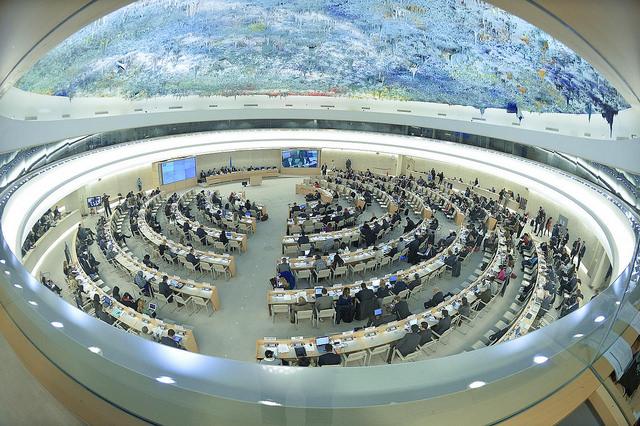

Australia officially launched its candidacy for membership of the United Nations Human Rights Council for the 2018–2020 term in October last year. If elected to a seat in the 2017 vote, Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop said Australia would aim to ‘advance human rights in practical ways that have far reaching systematic effects’. Given that it’ll be up against France and Spain, with a reliable bloc of EU votes, Australia will need to prove its genuine interests to the claim. One way to do so would be to turn its attention to Myanmar—where human rights concerns are plentiful—to address ongoing violations in the country.

‘Nope, nope, nope’ were former prime minister Tony Abbott’s words when confirming that Australia wouldn’t resettle any of the 8,000 Rohingya refugees stranded at sea last May. Abbott pointed the finger at Myanmar for ‘letting the asylum seekers leave’ and went on to say it was the regional responsibility of the Myanmar’s closest neighbours to tackle the issue. Rather than playing the blame game, the sensible route would be for Australia to acknowledge its own regional responsibility and engage in addressing the human rights violations—the systemic root of the reasons people seek to leave Myanmar.

Myanmar’s made recent progress in its peace process and national reconciliation efforts. But ongoing human rights abuses have seen an estimated 94,000 persecuted Rohingya and Bangladeshis flee the country since early 2014, some landing close to Australia’s shores.

The country’s minority Rohingya Muslim population have long suffered from discriminatory policies and practices, including the arbitrary deprivation of nationality. Under the 1982 Citizenship Law, the Rohingya population were deemed stateless in Myanmar, afforded no real protection and left vulnerable to human rights violations. Despite pilot citizenship verification programs, many are still subject to other restrictions across Rakhine State, where the majority of Myanmar’s Rohingya population live.

Local orders in Rakhine State—discriminatory policies and directives issued by local authorities—have been in place since the mid-1990s. They set out punishable offences and prescribe broad powers to local authorities to enforce selective restrictions on marriage, childbirth and on the freedom of movement of the Rohingya population. Restriction on the freedom of movement can hinder access to education, health care and other basic services. The implementation of discriminatory practices in Rakhine State—which are said to be the root cause of irregular migration movements—remains unresolved.

Last month, in a commendable move, the National League for Democracy (NLD) government announced of the establishment of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State. Unfortunately the chair of the Commission, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, has confirmed the Commission’s mandate doesn’t extend its powers to conduct human rights investigations, but will focus on finding impartial solutions to ‘support development’ in Rakhine State. If human rights abuses—including the local orders in Rakhine State—continue to be overlooked, the country’s Rohingya minority population will be increasingly segregated, stifling the country’s national reconciliation process. Contrary to Tony Abbott’s view, that isn’t just a problem for Myanmar and its immediate neighbours.

Australia’s missing an opportunity by not championing human rights in Myanmar. Australia should call on Myanmar to immediately tackle the legislative changes required to verify citizenship of persecuted minorities. The country should also be encouraged to pursue an immediate human rights investigation into the local orders in Rakhine State. In doing so, Australia can leave its reputation of turning a blind eye to regional human rights concerns behind and prove its commitment to being an international champion of human rights.

And though successful in some contexts, state-on-state engagement with Myanmar doesn’t need to be adversarial. As well as standing up for human rights from afar, Australia can take positive action on the ground, by providing apolitical professional military human rights education, in settings such as the recent peacekeeping training course. Australia should draw on its past engagements with Myanmar and the Tatmadaw, including its now discontinued human rights training program, to develop a new program that keeps up with the changing political landscape.

Australia is well placed to capitalise on the move to democracy in Myanmar, and to nudge the NLD government to address concerns on a local level to complement Australia’s engagement. Not only would it strengthen Australia’s claim to a seat on the UN Human Rights Council, but addressing instability in Myanmar would also align with its interest in a stable and prosperous region.