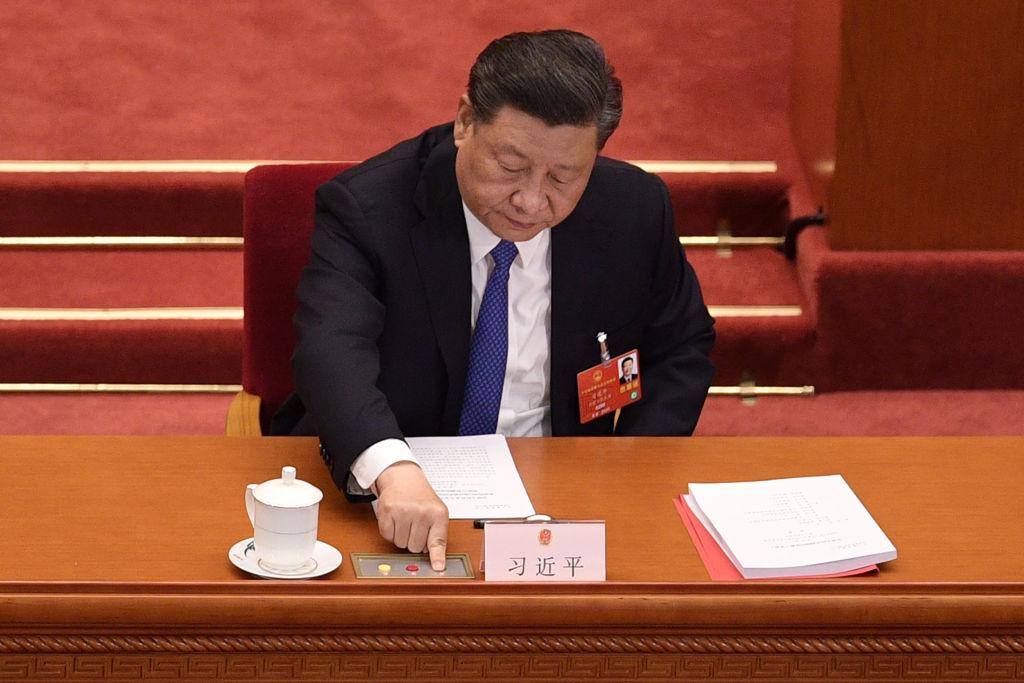

At the Boao Forum in April Chinese President Xi Jinping said the world needed ‘justice, not hegemony’.

He said China would never engage in an arms race or boss others around and ‘meddling in others’ internal affairs will not get one any support’.

Xi’s words are reproduced by China’s mass-media machine without criticism. Questioning official Chinese Communist Party narratives is not permissible domestically and internationally—China has created a new national security law with extraterritorial scope.

Against this backdrop we consider the emerging new boundary lines of free speech and the concerns of some journalists and scholars who assert that anti-Asian sentiment is linked to the current conversation about strategic competition with China.

With the Covid-19 pandemic and the Atlanta mass shootings in which women of Asian descent were murdered, some argue that to support Asian–American citizens, rightful criticism of the actions of the Chinese government should be lessened. That’s argued even though some of the CCP’s policies are abhorrent, like its human rights violations against the Muslim Uyghur minority, or threaten the national interests of other nations, such as its illegal island-building endeavours in the South China Sea, the increasingly ominous threats to punish Australia for a variety of ‘transgressions’, and foreclosing on debt to acquire foreign assets.

Some Western scholars theorise that generalised anti-Asian sentiment emanates from the current conversation about strategic competition with China and argue that supporting citizens of Asian descent requires toning down concerns about China. This line of thinking may be well-intentioned and intended to support Americans of Asian descent and to acknowledge the dissonance they feel about ethnicity, nationality and belonging. However, not all citizens of Asian descent are Chinese. About 80% of Asian–Americans are non-Chinese.

Some 40% of all Asian–Americans were born in the US. They’ve known no other political system or cultures and find CCP practices as abhorrent as do most other Americans. Connecting the issue of anti-Asianism with foreign policy on China is based upon an illogical connection. Racism is eliminated by addressing racial bias and creating a more inclusive society, not by changing foreign policy objectives and priorities.

Serious fault lines exist in what amounts to an appeasement strategy that silences legitimate criticism of CCP policies and actions. Historically, appeasement has been unsuccessful as a policy strategy and current experiences lack evidence to support it.

There’s no proven correlation between critiques of CCP policies and actions with a spike in anti-Asian sentiment. What has been correlated is racist commentary about Asians and a rise in anti-Asian sentiment. The racist remarks about the ‘kung flu’ made by then–US President Donald Trump, for example, led to a rise in incidents against Asians, but the Congressional resolution to condemn China for its human rights abuses in Xinjiang did not. Some scholars and Chinese state media assert it is ‘self-evident’ because there is no real evidence of a causal link between foreign policy and a rise in racism.

Silencing legitimate criticism plays directly into the CCP’s hands. The party’s default strategy whenever Western nations criticise China over human rights abuses or sovereignty issues is to claim they are ‘meddling’, ‘racist’ and ‘Sinophobic’.

But many Western democracies have a long history of challenging injustice and they should continue to do so. While complicated by economic factors, the United Kingdom’s anti-slavery sentiment undermined the secessionist cause in the American Civil War. Many nations fiercely advocated for the end of apartheid in South Africa. The need to make slavery reparations to African Americans has been debated internationally. The international community has worked together to convict war criminals of crimes against humanity committed in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia.

Democracies such as the US, Australia, Canada, the UK and the EU countries should not be mute about the many credible reports of atrocities carried out by Chinese officials including torture, rape, beatings, forced abortions and children stolen into state institutions.

The notion that criticism of CCP actions leads to generalised anti-Asian sentiment is simplistic and dangerous. Racism is abhorrent and all countries face problems of racial equality. Through US history, there’s a continual line of suffering from social, racial and gender inequality but the nation has worked hard to reduce these inequalities. Many will legitimately argue that change comes too slowly. But protest within democratic societies is allowed; citizens can vote. The US continues to atone for its greatest national shame, slavery, by correcting its legal system and attempting to eliminate racial bias through national conversation, protest and legislative change.

China, Russia and Iran say it’s hypocritical for America to promote democracy while continuing to exhibit inequalities in its own society and say the US is not fit to lead.

For China, the reality is that, instead of achieving Marxian ideals, the CCP has institutionalised a power structure that largely benefits the privileged princelings (太子党 taizidang) and wealthy second-generation elites (富二代 fuerdai) of Mao’s revolutionary colleagues, China’s new very wealthy bourgeoisie.

Corruption and class exploitation will continue to plague China because its civil society has been silenced.