Recent strident assertions by former Australian prime minister Paul Keating that NATO has no place in Asia and should limit itself to Europe and the Atlantic and not try to expand into the Asia–Pacific are misjudged and should not be allowed to pass unchallenged.

With global commerce and security interests more interconnected than ever, NATO, the world’s premier political-military alliance, and one of the most successful collective security enterprises in history, understands that developments in the Indo-Pacific region are highly relevant to global cooperative security.

Regional and collective defence commitments will always be paramount for NATO but cannot be its defining perspective in an increasingly globalised, interconnected and uncertain world. NATO’s interests do not stop at the Tropic of Cancer in the Atlantic. Contrary to the views of Keating, NATO has a vital interest in a stable Indo-Pacific region, including unhindered lines of communication on, under and above the region’s oceans and seas. This was reaffirmed at the recent NATO summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, where the alliance’s 31 member states agreed that what happens in the Indo-Pacific matters for Europe and therefore for NATO. And, conversely, what happens in Europe matters for Indo-Pacific nations.

Over the past decade, the centre of world power has been shifting from Europe to the Indo-Pacific region. Taking this into account, NATO, which includes three Pacific Rim members—the US, Canada and France—is considering the substance and direction of its regional interests and bilateral cooperative security relationships with its four Asia–Pacific partners. Similarly, these partners—Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea—are considering the best way in which they might each interact and cooperate with NATO, cognisant of their unique geographic and strategic environments. This doesn’t translate into expanding NATO membership and collective defence into the Indo-Pacific. It does, however, need to manifest itself in clear and precise bilateral partnership objectives, opportunities and engagement.

The global maritime trading system, in particular, is one that no one owns but all benefit from. The impact of trade, containerisation and just-in-time supply chains means that good order at sea in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, including the South China Sea, is just as important to NATO members as the security of trade and shipping in the Atlantic and Mediterranean is to Indo-Pacific nations, including China. It is a system that can only work effectively if there is a strong and determined cooperative and collaborative rules-based international effort to keep the global commons functioning. It is an area where the geostrategic interests of NATO and its Indo-Pacific partners increasingly intersect.

Importantly, the rise in wealth and defence expenditure in the Indo-Pacific is occurring in midst of numerous simmering and unresolved maritime territorial claims, disputes and nuclear crises in the region, including China’s threats over Taiwan and its territorial claims and belligerence in the South China Sea. NATO is not immune from such developments and will not have the luxury to choose the future strategic challenges it will face.

The NATO summit in Vilnius highlighted the growing consensus among NATO members and Asian democracies that China’s increasing power and territorial ambitions pose a significant challenge to global security. The summit’s communiqué criticised China’s ‘coercive policies’ and attempts to ‘subvert the rules-based international order’. While NATO’s focus has traditionally been on Russia, the communiqué’s emphasis on China indicates a significant sharpening of focus. The statement also highlighted China’s attempts to control key sectors, infrastructure and supply chains, and to create strategic dependencies. It did, however, emphasise the importance of constructive engagement with China.

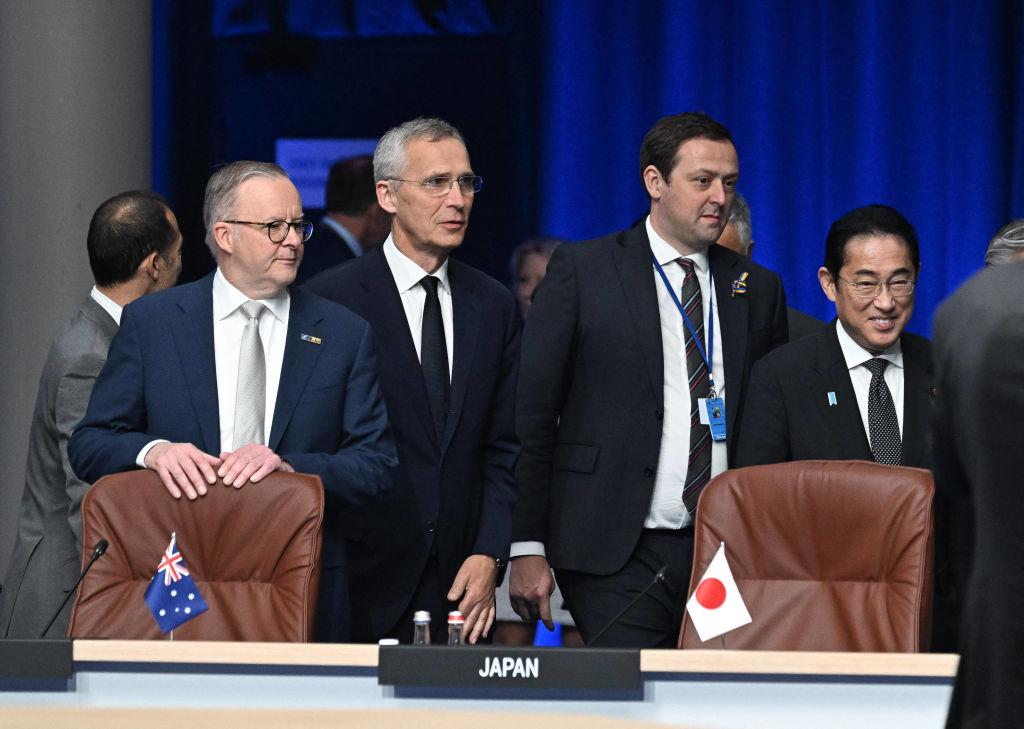

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese stated—rightly, in my view—that democracy, not geography, should define a nation’s interests. At the NATO summit, he argued that the struggle between democracy and autocracy is being fought in the Indo-Pacific, with China as a key antagonist. He claimed that China is modernising its military without transparency or assurance about its strategic intent. Speaking to NATO leaders, Albanese said Australia was under pressure from China, but the government’s response was principled and level-headed. He added that Australia would cooperate with China where possible, but would also disagree where necessary and always act in its national interest.

UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace, meanwhile, has warned that the West must develop a more coherent political strategy towards China’s expansionist activities in the South China Sea or face a conflict within a decade. In a recent interview with the Sunday Times, Wallace said that China’s aim of constructing new islands and stationing military equipment in the region could lead to a ‘total breakdown of politics in the Pacific’.

While we live in a multipolar world, it is clear that the Indo-Pacific is becoming the stage of intensifying strategic competition—not only military or economic competition, but competing visions for the global order. Above all, the relationship between the United States, the leading member of NATO and a significant Pacific power in its own right, and a rising, prosperous and increasingly confident, assertive and coercive China will, more than any other, determine the outlook for international security and prosperity. Strategic competition between the US and China is a reality, but both should actively seek stability, not conflict, and that should be encouraged by NATO and its partners in the region.