American military historian Roger Spiller, delivering the keynote speech at the Society for Military History, argued that what Carl von Clausewitz and Hans Delbruck ‘had in mind’ when writing history ‘was not the application of military history so much as the application of the military historian’. For them, Spiller argued, military history and commentary on the military of the day were two sides of the same coin. Yet, he lamented, few military historians turn their attentions to contemporary military operations.

One response to Spiller is that it’s difficult for American historians to do so, in the absence of unclassified records or a deep personal connection with contemporary conflicts. Yet, in many ways the US military is better off than that of Australia in how it creates, distributes and uses its history.

There are a number of ‘command historians’ scattered throughout the US armed forces, from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to US Special Forces. A host of unclassified campaign histories of recent wars have been released by the services, covering the early war in Afghanistan and doctrinal and organisational histories.

Within the Australian Defence Force, historical work is scattered throughout Defence, but is largely concentrated in three centres: the Australian Army History Unit, the Sea Power Centre and the Air Power Development Centre, all based in Canberra. Each has a number of different roles and mandates, ranging from writing public history to supporting academic publications to informing contemporary debates.

These centres are the public face of broader historical work in the ADF, but each service maintains sections that produce what can be broadly described as ‘lessons learned’ studies. Using the Army as an example, the Centre for Army Lessons, Australian Army Research Centre, and individual corps and units all produce studies of their past above and beyond the ubiquitous post-operational reports (PORs). Rarely is the work done by these groups available to the public.

Studies of Australia’s military past produced by those with access to contemporary documents are therefore scattered and, through no fault of each group, often narrowly focused in scope and timeframe.

Undoubtedly, official histories address some of these issues. The quality, reach and depth of the most recently completed official histories, David Horner’s Official History of Peacekeeping, Humanitarian and Post-Cold War Operations, provides many lessons for the ADF. The current official histories, examining operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and East Timor, will hopefully shed light on these conflicts.

The independence of the historians (rare compared with other nations’ official histories) and the fact that their final product will be unclassified, allows for a broader discussion to occur outside the ADF, broadening the debate and learning opportunities.

However, these histories are only part of the answer. Each official history is commissioned separately and is largely dependent on the support of the government of the day. The decision to employ academics, while maintaining a degree of separation from their subject, raises questions of how far these historians are allowed ‘inside the tent’.

What’s missing, currently, is the placement of historians in positions where they can aid the ADF in interpreting and using its past as those events are experienced, as the documents are produced and as lessons begin to be learned. Old PORs are not history.

Scholars in these positions would be less tied to the tyranny of the present, could potentially draw together the variety of different intentions of those ADF centres that deal with the past, and could add nuance to any internal historical debate.

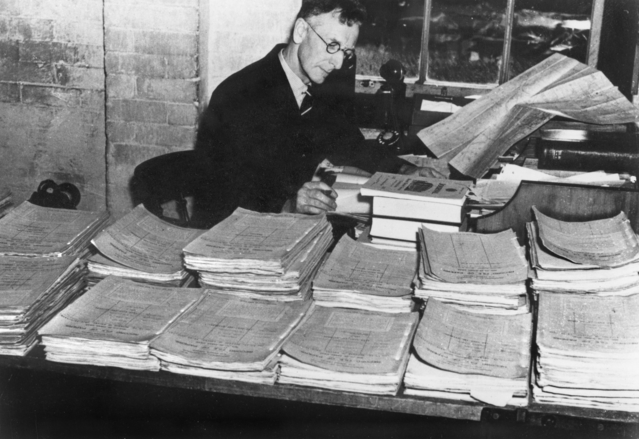

The employment of historians within the ADF would also aid the preservation of key sources. History is layered: the neat article or book is only the most visible tip of a broader literature comprising documents, oral histories and ephemera. As an historian can attest, however, so much of this material is lost before it makes it to the archives.

Identifying groups of documents, collating them, compiling a comprehensive collection of oral histories, and encouraging and educating serving members about their role in compiling the record of their actions for later use is of inestimable importance. This is particularly the case in the context of the ‘digital black hole’ that has arisen as institutions, archivists and historians grapple with finding, preserving and using digital materials.

More broadly, the placement of a historian in a command, such as the Joint Operations Centre or Forces Command, would potentially bridge the gap between the production of the building blocks of history and their use within the ADF today and by scholars in the future.

Of course, the embedding of historians within Defence would raise a number of issues. Accusations of ‘weaponising history’ and compromising independence are two. However, the alternative is no expert history at all.

At the same time, there’s the perennial issue of information security, to which the ADF is particularly sensitive. There would also be a tension between academic career requirements—most notably regular publication—and the internally focused and classified work that historians may be asked to do.

These challenges may well be insurmountable. But by dint of being a permanent position, a command historian has the potential to build trust over the long term. Equally, the ADF’s current strong focus on professional military education, and the recent growth of impressive new websites such as Grounded Curiosity and The Cove, and podcasts such as The Dead Prussian, which have a strong history focus, offer a window into a more open and historically engaged ADF.

Making use of military historians—embedded within the ADF and with a clear mandate—would be a significant next step in the pursuit of understanding the institution’s recent military past.