I read David Connery’s recent Strategist contribution, ‘Adding to the picture: The UK’s serious and organised crime threat assessment’, with much interest. David made some excellent points in relation to the post prosecution management of recidivist organised crime offenders. The National Crime Agency, and its predecessor the Serious and Organised Crime Agency, has for many years pioneered a range of organised crime intervention strategies.

I found David’s comparison of the Australian Crime Commission and NCA’s reporting approaches of particular interest. In making his comparisons, David doesn’t appear to have taken into account the substantive differences between the roles of the ACC and NCA, nor the purposes of their respective reports.

To understand the purpose of the UK’s serious and organised crime threat assessment, it’s crucial that the role that the NCA plays within the United Kingdom’s National Intelligence Model (UKNIM) is considered. The UKNIM is a national law enforcement business model based on intelligence-led policing theories. More specifically, it’s a multi-tiered system that’s focused on information collection and enforcement prioritisation across all of the UK’s police forces.

The UKNIM provides policy and strategy decisionmakers with an understanding of their operating environment so that they can identify, endorse and disseminate priorities to all UK law enforcement and regulatory agencies.

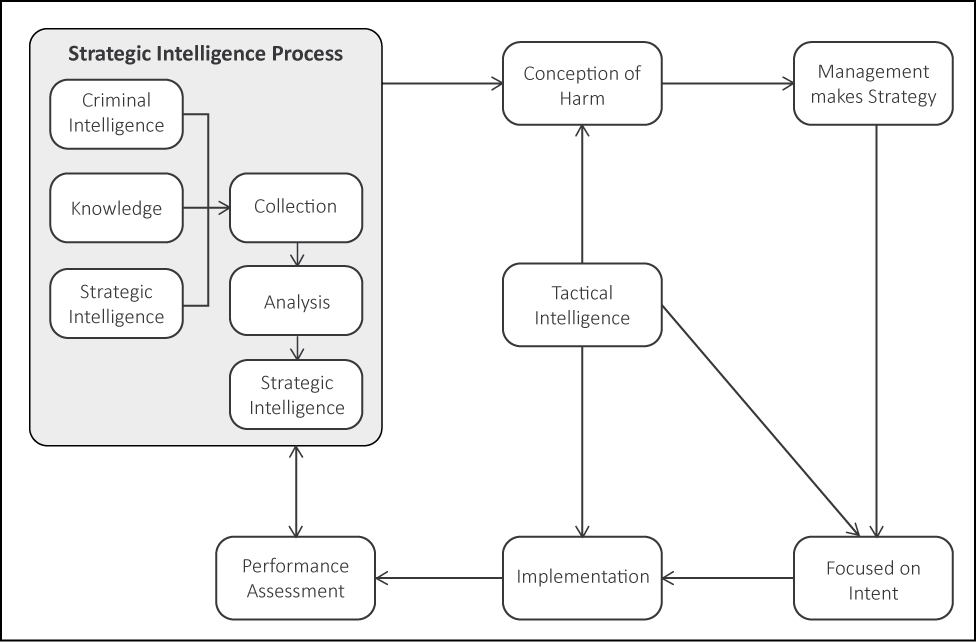

As illustrated in the following diagram the NCA’s report is designed to provide senior decisionmakers with a macro understanding of criminal threats and markets. With this understanding, the NCA—and its clients—make strategic decisions on organisational and target priorities in the form of strategic intent. This is translated into operational priorities through the UKNIM’s structured meetings between law enforcement agencies and organisations.

In contrast, the ACC’s organisational framework is focussed on organised crime as a national problem; a problem that’s a threat to Australia’s human security.

In practice the ACC seeks to gain an understanding of Australia’s criminal environment from a Commonwealth perspective. National risks and threats are viewed in practice through a Commonwealth lens focussed on combating multi-jurisdictional organised crime—as opposed to organised crime more generally.

With a Commonwealth lens the national organised crime risk and threat is an aggregation of issues from multiple state and territory perspectives, as well as the federal jurisdiction.

Unlike the NCA, there’s no formal link between the ACC’s national assessment and task prioritisation or resource allocation of the wider Australian law enforcement community. This is due mostly to Australia’s federated approach to law enforcement.

In this federated approach, the Australian Federal Police, ACC and their state and territory partners all operate rigorous case categorisation and prioritisation models. These models are informed by a range of factors including harm assessments.

When it comes to organised crime it’s easy to adopt a militarised ‘war on organised crime’ perspective that’s focussed primarily on threat assessments. But this threat approach often requires intelligence, threat and risk analysts to over-generalise in their assessments to achieve a workable degree of granularity in prioritisation.

I believe that the organised crime challenge is amorphous in nature. And adversarial models that generalise the problem prevent the development of evidence based disruption or harm reduction.

Organised crime responses to law enforcement disruptions in Australia’s illicit drug markets illustrate this point. When law enforcement disrupt organised crime syndicates, a gap in the global supply chain is created. In the Australian context, despite record seizures and arrests, illicit drugs remain readily available in the Australian market. This reveals the ability of organised crime groups to rapidly occupy gaps in the supply chain.

I wouldn’t like to see a threat assessment or ACC organised crime report that prioritises threats. It would be better to see future assessments focussing on providing assessments of harms that augment the threat perspective. In this context harm refers to the negative outcomes to human security generated by the activities of organised crime groups. It would then be possible to design strategic interventions focussed on harm reduction as an outcome as opposed to regulation and enforcement.

Secondly, assessments that are focussed on understanding the value chains of illicit markets place greater emphasis on strategic interventions that have longer-term disruptive impacts.

In 2008 the AFP and Cambodian National Police proved the effectiveness of both of these approaches. At the time the global production of MDMA was exploding. The key precursor for the production of MDMA is safrole oil. Through strategically focussed disruption operations the AFP and CNP were able to seize and destroy enough safrole oil to produce some 245 million MDMA tablets.

The seizures subsequently created a global shortage of safrole oil. This shortage directly contributed to a global decline in the production of MDMA that would last for almost five years. The operation did not result in any arrests or seizures within Australia but significantly reduced the harm to Australian communities created by MDMA.