Rod Lyon presents a refreshingly sophisticated case against a no-first-use or sole purpose declaration being made by the United States. In particular, he highlights the need for America to reassure East Asian allies in order to prevent nuclear proliferation—an important issue often overlooked by disarmament proponents.

Rod appears to overstate the case though, and to explain why it’s worth unpacking some of the detail.

First, the debate about sole purpose occurs in the context of current declaratory policy. America’s Negative Security Assurance (NSA), announced in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, presently reads as follows:

The United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.

So we must begin by identifying the difference between America’s NSA and a sole purpose declaration. Simply put, the NSA excludes a range of states from being possible targets for US nuclear weapons, a sole purpose declaration would say something about when the US believes it may use nuclear weapons against the remainder. Currently the United States leaves open the option of nuclear first use against those states.

Rod identifies the only credible scenario—the United States facing conventional military defeat in a major conflict close to the home territory of a regional power.

Given the overwhelming strength and skill of the US armed forces there are only two feasible contingencies in the foreseeable future: 1) a Russian invasion of the (NATO-allied) Baltic states; and 2) a US–China war, perhaps over Taiwan.

Next, we must assess the likelihood of the United States escalating to the nuclear level in both of those contingencies.

The first scenario is a non-starter. There’s no chance that the United States will seriously contemplate a nuclear war with Russia over the Baltic states. Moreover, there’s no prospect of convincing the Russians otherwise. The United States lived with Soviet occupation of the Baltic states for fifty years during the Cold War and can do so again. Given that Russia enjoys greater parity with the United States in its nuclear arsenal than in conventional arms it’s also decidedly unclear what advantage the United States could hope to gain through a nuclear escalation.

In a US–China conflict, by contrast, the United States has a much greater incentive to launch a nuclear first strike due to its advantage over China in tactical nuclear options in this predominantly maritime theatre. After incurring a tactical nuclear strike China’s only options are either: a) accept a military defeat, b) retaliate against the United States at the strategic level, or c) as I game out in this two-part video, conduct a strategic nuclear strike against a non-nuclear US ally, such as Japan.

While a sole purpose declaration by the United States may indeed make East Asian allies nervous, we must also weigh that against the risks of not doing so.

The prospect of a new nuclear arms race is accelerated and intensified by the proliferation of ballistic missile defences. If the United States were to launch a major nuclear strike against China then China’s nuclear arsenal would be reduced to a small fraction of its already modest size. That would make China’s retaliatory strike highly vulnerable to interdiction by ballistic missile defences.

China is therefore highly likely to respond to America’s first strike posture and BMD deployment by developing a vast nuclear arsenal of its own. At that point it’ll be impossible for the United States to adequately reassure its allies in the Asia-Pacific region. In other words, we’ll all be contending with a resurging and militarily assertive China and nuclear proliferation across the Asia-Pacific region.

This doesn’t mean that a sole purpose declaration is a panacea or even especially advantageous. Far more urgent and useful is having a multilateral treaty in place that prohibits low-yield nuclear weapons. This will further entrench the firebreak that exists between conventional and nuclear war, and strengthen the ‘ceiling’ that Rod refers to on conventional conflict between nuclear powers.

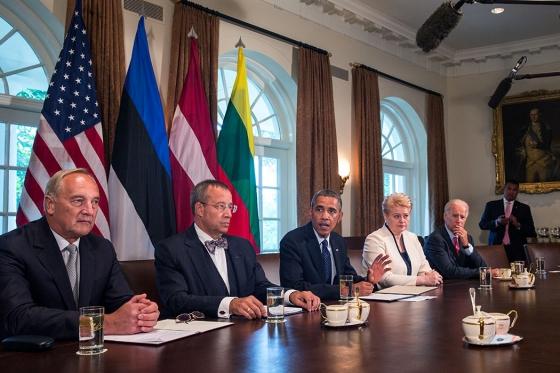

Crispin Rovere is a former PhD student at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, ANU and co-author of Non-strategic nuclear weapons: the next step in multilateral arms control. Image courtesy of The White House.