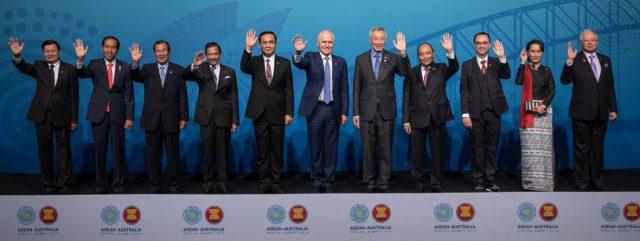

By all accounts, the ASEAN–Australia summit was a success. The Sydney Declaration complemented the existing 2015–2019 Plan of Action to Implement the ASEAN–Australia Strategic Partnership. These documents give a long list of policy issues both sides need to work through in the coming years.

Yet, the more spirited conversations at the Sydney gathering turned to consideration of whether Australia should join ASEAN. Sparked by Indonesian President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo’s comment that ASEAN membership for Australia is ‘a good idea’ (if other members agree), analysts have debated whether this represents a genuine opportunity or simply false leads.

Some wondered if Jokowi was serious or being polite, while others asked if the idea was genuine or just a domestic political football in Canberra. Some questioned if Australia is prepared to ‘dance with dictators’, while others argued that Australia can help ASEAN meet a plethora of regional challenges.

But as far as we know, no serious public proposal has been tendered and no serious invitation has been extended. Nor is it clear whether full membership is sought, or some form of an ‘upgraded’ dialogue partner status (what Graeme Dobell calls ‘Community partner’).

For the sake of argument let’s put aside the question of motives or asymmetrical ‘cultural’ gaps between ASEAN and Australia. Instead, let’s consider whether ASEAN membership for Australia (in whatever format) is desirable for both sides. One way to do that is to pose a series questions about the implications of Australian membership.

The first relates to the fact that ASEAN would have more members and thus more interests to align. Finding common strategic ground sufficient to allow the group to act in unison will be harder if there is an 11th member.

If ASEAN is already divided—say, over the South China Sea—how will the addition of Australia change that? Australia will never have the same credibility and gravitas in the group as long-time members (or the original five founders). Could Australia then, for example, lead the way to amend the ASEAN charter to allow the ‘ASEAN-minus-X’ decision-making formula to apply to non-economic issues?

The second considers what Australia brings to the table. Analysts have argued that Australia brings plenty of ‘middle-power heft’ that could help the region deal with strategic uncertainties, including perhaps providing financial and human resources to boost the ASEAN Secretariat. In other words, Australia has ‘strategic assets’ (economic, political or security) to offer ASEAN.

But what sort of middle-power diplomacy can Australia pursue through ASEAN if the group requires consensus to act? ASEAN’s history suggests that the group can only act to address regional challenges when one or several of its members rally the others. Will ASEAN allow Australia to lead on, say global governance, if Canberra’s diplomatic agenda contradicts the domestic political interests of older members of the grouping?

Meanwhile, how can Australian financial resources ‘reform’ the secretariat? Article 30 of the ASEAN Charter clearly states that the secretariat’s budget is based on equal contributions, which means Australia’s ‘share’ would be the same as those of Cambodia, Laos and Indonesia. Any discussion to change this principle will revive fears that unequal contributions means unequal power.

Economically, how would Australia’s economy assist and help narrow the developmental gap among ASEAN members? What economic or financial benefits can Australia offer by being a member that it doesn’t already give through existing channels? After all, Australia’s $101 billion two-way trade with ASEAN last year happened without a membership card. How would ASEAN’s Open Skies policy or free movement of people as part of the ASEAN Community project affect Australia’s economy and national security?

What about Australia’s much more capable defence force that might spur ASEAN to ‘stand up’ to China? Unfortunately, there’s no ASEAN mechanism that would allow the ADF to be ‘deployed’ alongside ASEAN military forces to patrol the South China Sea, for example. For that matter, ASEAN doesn’t even have a standing regional military force.

In short, ASEAN’s multilateral institutions could very well ‘neutralise’ the ‘strategic assets’ that Australia could bring to the table. Perhaps if Australia somehow gained primus inter pares status inside ASEAN sufficient to drive internal reform processes, then Australian membership would benefit both sides. But if Australia’s stature in ASEAN is equal to say, that of Cambodia, then those assets would be heavily diluted.

Finally, what would ASEAN offer to Australia? Australia would need to partake in the over 1,000 meetings per year that ASEAN organises, and at some point Canberra would have to host perhaps close to 300 meetings in a year as ASEAN chair. Assuming that financial resources are not an issue, other foreign policy priorities—from close alliance commitments to developments in the Pacific Islands—will take a back seat, if not in diplomatic focus then at least in energy.

As well, Australia would need to face up to a belligerent China (presumably unhappy with another US ally as an ASEAN member) in the painstaking code of conduct negotiations over the South China Sea. Currently, as a leading dialogue and strategic partner of ASEAN, Australia can help shape the regional architecture without ‘confronting China’ or rocking the boat too much. So, what specific benefits can ASEAN give Australia that the group hasn’t already extended since 1974?

These are difficult questions requiring level-headed practical examination. In any case, there are plenty of hard policy challenges that ASEAN and Australia can and should tackle as strategic partners, as the Sydney Declaration makes clear.