Orwell’s dilemma: more reflections on intelligence oversight

Posted By Nic Stuart on June 25, 2013 @ 12:00

[1]

[1]When the moment finally came, Eric Arthur Blair (or, as he’s better known to history, the author George Orwell) had no doubt. The Eton-educated writer did his duty. He handed a list of 38 names—all, he believed, ‘crypto-communists, fellow travellers, or inclined that way’—to a female friend who was working for the Foreign Office. It was a blacklist; people he believed couldn’t be trusted to write anti-communist propaganda.

What makes the list significant is that Orwell wasn’t a nationalist who believed in his country, ‘right or wrong’. He’d fought for the anarchists in the Spanish Civil War; was rejected by the British army (on medical grounds) in World War II; and wrote for the left-wing weekly newspaper Tribune instead. His entire life was about choice and commitment.

Hence the list. Given the choice, Orwell didn’t hesitate before committing himself to British democracy rather than Stalinist orthodoxy. Despite his intense and unremitting opposition to the class-based society he’d savaged in books like The Road to Wigan Pier [2], Orwell knew life in Britain was preferable to the grim Soviet alternative. So the author turned informant (although the fact that he really happened to fancy the woman asking for the information might have swayed his mind as well).

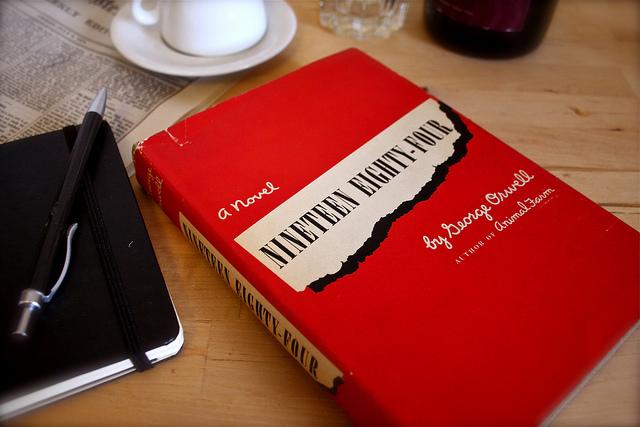

Today Orwell’s work has suddenly become sought after again. Edward Snowden’s revelations of the extent of state surveillance have made Orwell fashionable again. Sales of his dystopian novel 1984, soared by 6,021% in a single day [3].

But what makes the book so horrifying, and so plausible, is its very banality. This is, after all, the nature of evil. Orwell faithfully records how Oceania—the nation he creates—differs from his own England so we realise how fragile the fabric of our democracy is. In the first line of the book the clock strikes thirteen. It’s so close to the truth (when Orwell was working for the BBC and broadcasting to the Empire from Bush House, the World Service always used the 24-hour clock) and yet so far from ordinary usage that it sets the scene perfectly. He emphasises that there’s nothing inevitable about the triumph of good.

Similar light touches through the book deftly emphasise the inherent fragility of our own civilisation when pitted against the ruthless, arbitrary omniscience of the world of Big Brother. Orwell’s point is that modern technology has enabled the apparatus of control necessary to establish a totalitarian state. The Party exploits this and, by 1984, is in complete control of Britain (renamed ‘Airstrip One’). As outsiders, we can see that the hierarchy of the Inner Party is based around the exploitation of the proles, who understand nothing. They’ve been lulled into stupor with repetitive slogans like ‘our new, happy, life’ and ‘thoughtcrime is death’.

The book ends (spoiler alert!) when the hero, Winston Smith, accepts the mindless jingles as he gazes up at an image of Big Brother, overcome with love. He has learnt to dismiss his individuality, submerging his own personality into the whole. Smith has never been happier.

In the wake of World War II everybody understood that Big Brother was Joseph Stalin. That’s why his communist friends wouldn’t publish the book. But it’s much more than just an attack on communism. Orwell was warning about something far more insidious, which is why he emphasised the new surveillance and control technologies that he foresaw would dominate the modern world.

Orwell also understood the ease with which good can be transformed into evil. The Party’s members quite genuinely believe themselves to be acting for the greater good. Their motives are pure. Rather than simply disposing of the threat represented by Smith and killing him, the Party puts considerable effort into helping him become aware of his own selfishness and error.

At the end of the book Smith listens to the announcement of another ‘great victory’ over the Eurasian forces. He knows this is nothing but propaganda; more pap to keep the workers happy. But he’s suddenly overwhelmed with love for Big Brother. He understands the Party is working for the greatest happiness of the greatest number. He knows he deserves to die for his doubt. It’s the Party’s final victory. It now controls his mind.

And so, ineluctably, to Prism [4], the glorious soaker-up of every scrap of electronic information; from the illicit web-sites I’ve been visiting through to every known terrorist I’ve ever attempted to make contact with. I don’t think anyone would consider me much of a threat but the same can’t be said of some of the people I’ve contacted. Or, perhaps, some of the information I’ve come across.

So are the Western democracies becoming a shadow of Big Brother’s Oceania and is Prism a new way of identifying people in danger of committing thoughtcrime? Put it that way and the idea is obviously ridiculous. It’s like the fantasy of a deranged survivalist in the Appalachian hills, or bizarre loners in the bayou of the Gulf.

Typically, bureaucracies in possession of masses of data are unable to harness it in a useful way, but that’s not really the point. The real issue with Prism isn’t the power it offers the bureaucracy, but rather the issue of oversight. There are already numerous checks—the question is, are they transparent [5]?

Orwell’s list—the 38 names he provided to the security services—were an effort to increase visibility. He correctly identified more than one person who was later discovered to have spied for Moscow. He knew the way his society worked so intimately that he could describe himself, with absolute accuracy, as ‘lower-upper-middle class’.

Truth, openness and honesty represent the currency of democracy. The concern about Prism isn’t that it exists—of course it does. The issue is simply what we don’t know what sort of supervision exists, and if it’s adequate.

Without full judicial and media oversight, there’s really nothing to distinguish our world from Orwell’s fantasy.

Nic Stuart is a columnist with the Canberra Times. Image courtesy of Flickr user Pestpruf [6].

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /orwells-dilemma-more-reflections-on-intelligence-oversight/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: https://aspistrategist.ru/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/5439174968_c7fa36486a_z.jpg

[2] The Road to Wigan Pier: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Road_to_Wigan_Pier

[3] soared by 6,021% in a single day: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/articles/477262/20130611/george-orwell-sales-1984-rise-edward-snowden.htm

[4] Prism: https://aspistrategist.ru/looking-through-the-prism/

[5] are they transparent: https://aspistrategist.ru/australian-intelligence-organisations-the-limits-of-oversight/

[6] Pestpruf: http://www.flickr.com/photos/pestpruf/5439174968/

Click here to print.