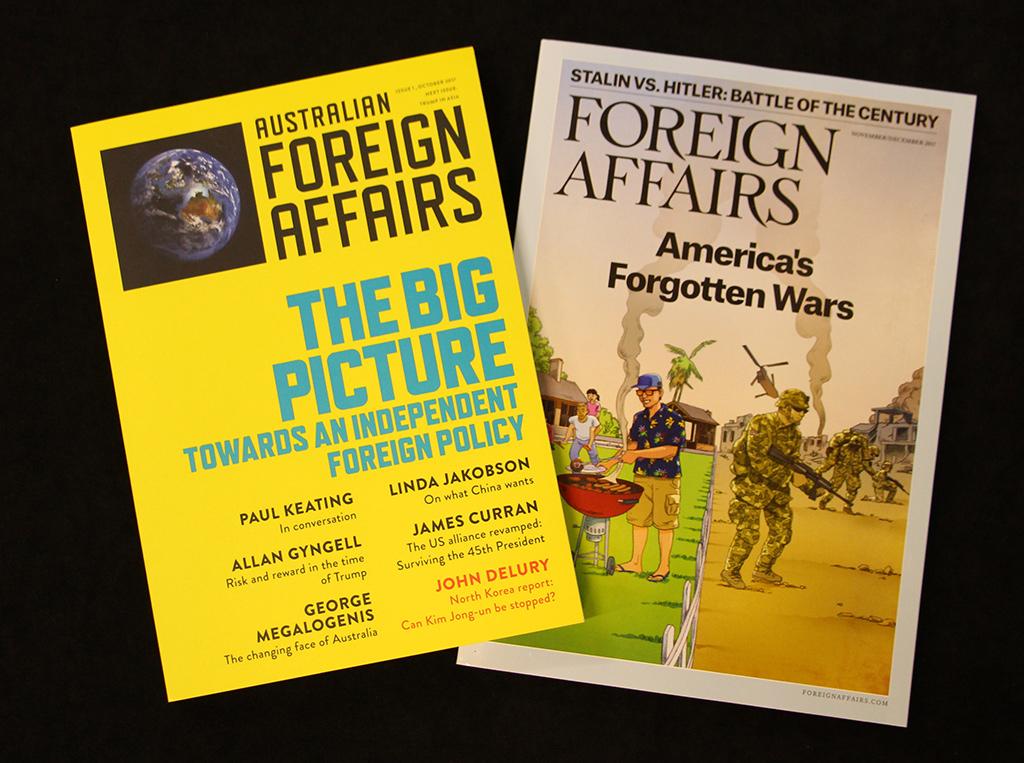

Simultaneous serendipity struck when the new magazine Australian Foreign Affairs and its US inspiration Foreign Affairs dropped into my mailbox on the same day.

The wattle-yellow cover of the newborn publication made a fine Oz contrast with the traditional light blue of the 95-year-old American heavyweight.

Oz Foreign Affairs lifts its title from America, but its style is more that of its stablemate Quarterly Essays, which proclaims as its aim to ‘make serious politics popular’.

In staking out territory, wattle-yellow Foreign Affairs won’t have to worry about the light-blue heavyweight swooping down too often: Michael Fullilove’s article in US Foreign Affairs on Oz responses to Trump broke a 40-year drought. It’s had plenty of articles written by Australians, but the last time an article about Australia appeared in the print edition of Foreign Affairs was 1977.

So welcome to a new star in the firmament of Oz international affairs. May it burn bright. Not least of the daring is that much of the strategy rests on print, aimed at subscribers or those browsing in newsagents and bookstores. What a novel idea: pay people to write interesting stuff, print it and then other people will buy it. Could catch on!

The publisher of Australian Foreign Affairs, Morry Schwartz, says he’s making money out of The Saturday Paper and The Monthly. He might put a dent in one of my standard one-liners: Nobody wants to pay for good foreign policy, but everybody pays for bad foreign policy. Let’s hope that the Morry magic can make foreign affairs profitable.

Journalist lore holds that the first edition of any publication is a dud—birth pains collide with deadlines and the initial iteration of ambition limps onto the page. Australian Foreign Affairs handsomely defeats the hoodoo. Certainly there’s no lack of ambition in the theme of issue one: ‘The big picture: towards an independent foreign policy’.

The debate starts with Paul Keating in sparking mode, arguing that Australia can put its interests first within the context of a US ‘alliance which is never going to fade away’. A confident Australia in Asia, Keating argues, should have equal confidence in its 100-year strategic partnership with the US: ‘We would never lose the Americans.’

Keating says Asia doesn’t want China to dominate and needs America to play the role of balancer and conciliator: ‘We need the US here, as the floating good guys, letting people know there are balances … What constitutes a Westphalian-type system of balance in East Asia is hard to know, but it should include the US.’

The magisterial Allan Gyngell addresses the core theme with typical smarts: ‘It’s not independence that Australian foreign policy needs, but substance, subtlety and creativity.’

Both Gyngell and the journalist George Megalogenis focus on how the changing nature of Australia will alter how we do foreign policy in fast-changing times.

As Gyngell notes, the content of our foreign policy and the way we do it are intimately tied to our national identity. And demographic shifts are challenging and changing Oz:

A new generation of policymakers, whose experiences and memories don’t go back much before the turn of the century and who have never known an unconnected world, will soon be in charge. And the Australian community now includes more than two and a half million people who were born in Asia. Both the millennials and the migrants will understand the past—and therefore imagine the future—in new ways. They will be less inclined to see geography as predicament, and less given to thinking about themselves as regional outsiders.

George Megalogenis lays out the figures to show the ‘epic transformation’ of Australia’s population from white Anglo-European to Eurasian. Stress George’s point that Australia has crossed the threshold: we are a Eurasian society, with migration from China and India driving the change.

The scale and content of the migration program since 2001—emphasising skills—have remade the face of Australia and the faces of Australians. Eurasian is not how many Australians think of their society. The population shift is already here, but it’s not uniform across the wide brown land. Melbourne and Sydney are where the Eurasian effect is concentrated. The hunt for a migrant scapegoat threatens to become a version of the old arguments that the rest of Oz always has with its two megacities.

Megalogenis judges that an Australia with two big Eurasian capitals can’t continue to behave as a white outpost in Asia:

Australia’s place in the 21st century will turn on this basic question of identity. Will we be comfortable in our Eurasian skin? If the answer is yes, then our old Anglo and European allies, and our rising neighbours in the region, will have a mutual interest in our prosperity. We will never be big enough to force the world to listen to us. But we can inspire it by our example.

Plenty there for a journal devoted to Australian foreign affairs to chew on: a banquet beckons.