Des Ball was an extraordinary Oz strategist in range and depth.

Des, who died last week, was a virtuoso on global strategy, Asia–Pacific security and Australian defence policy. He worked at the highest level on the perils of nuclear war yet also devoted years to helping Karen forces along the Thai–Burma border. To the Karen, he was ‘a big brain’ from Australia.

The big brain ranged across much territory: Australia’s need to defend itself in the post-Vietnam era; signals intelligence and the role of US bases on Oz soil; he was a leader in Asia’s second track attempts at transparency and strategic dialogue. Ball was a Cold War scholar who gloried in the opportunities flowing from the collapse of that superpower stalemate.

An academic who never held a security clearance, Ball could find and reveal secrets (the spooks worried about him for decades). This searcher for truth—a ferociously independent academic—was ever exact with his forest of footnotes. Nicholas Farrelly’s fine interview with Des Ball got his range into its headline: ‘a career with global impact’. Most of the quotes in this piece are from a book of essays honouring Des, perfectly titled ‘Insurgent Intellectual’.

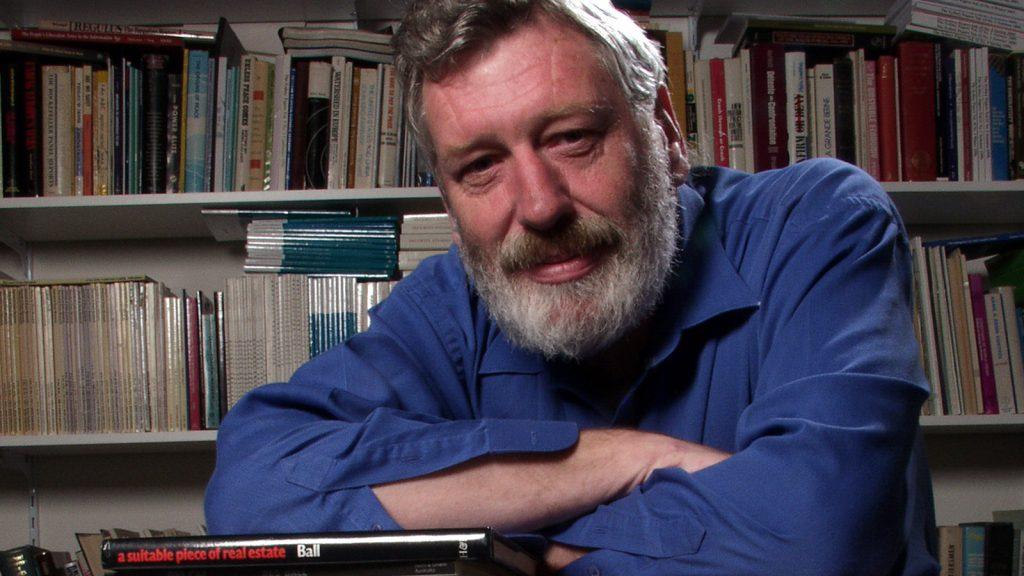

The bearded, bushy Ball was an Australian original, able to construct a roll-your-own cigarette with bushie aplomb—often using weed more exotic than tobacco.

Arriving at the Australian National University in 1965, he led protests against conscription for the Vietnam War, shifting from economics to strategy with a doctoral thesis on US nuclear missile doctrine.

The bohemian Ball—‘I rarely wore shoes in those days’—recalled that before his first trip to the US in 1970, Professor Hedley Bull gave him cash to buy a suit and shoes and insisted ‘that at least I wore those shoes’.

Based at the ANU’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre from 1974, Ball was a defence intellectual who could never serve inside Defence: ‘I would simply find it unbearable to work in Defence or under any direct or indirect official instruction.’

The former Liberal foreign minister, Alexander Downer, called Ball ‘an academic gem’ who caused government anxiety: ‘He has challenged, revealed, reviled and argued his way through the foreign policy and security debates of the modern era.’

The former Labor foreign minister, Gareth Evans, questioned: Is Des Ball a dove with hawkish characteristics or a hawk with dovish characteristics? Ball answered that he was a realist, as deeply committed to liberal institutionalism as the inductive approach.

Ron Huisken thought Ball defied ideological categories: ‘Des is what I would call a forensic analyst with a work ethic of Dickensian proportion.’ He had ‘absolute faith in the capacity of diligent scholarship to unlock all doors, especially those guarded by official secrecy.’ See this across Ball’s work:

Nukes: Ball had ‘an extraordinary career that took [him] to every high church in the nuclear priesthood’ (a wonderful phrase from Brad Glosserman and Ralph Cossa). His work came to focus on the operational aspects of nuclear targeting. Was limited nuclear war possible? Ball’s detailed answer amounted to a blunt, No!

Des recalled ‘heady days’ working and arguing with America’s nuclear elite—and sitting only feet away from the 1.2-megaton nuclear warheads atop the Minuteman ICBMs at a base. Former US president Jimmy Carter involved Ball in his arms control studies and wrote that Des ‘demonstrated the degree of wishful thinking behind concepts of controlled nuclear escalation. Ball’s work raised the possibility that if both sides were ‘blinded’ early in a nuclear exchange by the loss of [command, control and intelligence] facilities, a catastrophic slide into uncontrolled escalation and all-out nuclear war was a realistic possibility.’

US Oz bases: Ball told Australians what their government wouldn’t—the purpose of three US communications/satellite bases on Oz soil and why they’d be nuclear war targets. Ball killed a culture of secrecy that treated the bases as taboo. Kim Beazley said Ball’s work transformed the significance of the facilities for the whole US–Australia relationship. The knowledge Ball put into the public realm made it possible for the Labor Party to embrace the US bases and re-commit to the alliance. Australia moved to a position of ‘full knowledge and consent’ on the bases.

Asia: Ball thought Asia’s strategic culture was different from the US or Soviet Union. In 1992-93, he helped create the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia–Pacific as Asia’s premier non-government security forum. Ball wrote that CSCAP ‘developed many of the original practical proposals for regional security cooperation in the early 1990s, a lot of which were quickly adopted by the ASEAN Regional Forum.’ In Asia, Pauline Kerr wrote, Ball was a ‘realist with a difference’—building conceptual understanding and dialogue to tackle tensions, seeking new norms to influence behaviour and national interest.

Signals intelligence: Ball produced more than 30 books and papers on signals intelligence, and much of his other work discussed SIGINT as a key element. Jeffrey Richelson said Ball shone a light on the world’s eavesdroppers: ‘Des has been one of the pioneers, to put it mildly, in moving the detailed study of modern-day SIGINT into the academic and scholarly communities.’ Ball remembered how he was in Berlin on 9 November 1989, ‘when the Berlin Wall was demolished, watching the panicked Soviet intelligence officers based in the Soviet consulate desperately reacting to the loss of some of their covert technical equipment.’

Oz self-reliance: Post-Vietnam, the 1976 White Paper proclaimed self-reliant defence of the continent. Ball was one of the minds that worked out what Defence of Australia meant. Des walked the ground and flew the skies of northern Australia, describing the 1980s as ‘the golden age’ of Australian defence policy because of the work on a distinctively Oz military strategy and force. The old nightmare could be banished—Australia would defend itself.

Des Ball was a passionate Australian and a passionate intellectual, devoted to understanding dark topics and telling difficult truths.