The United Nations Human Rights Council recently voted on a resolution supporting China’s draconian national security law that has effectively crushed free speech and freedom of assembly in Hong Kong.

The resolution was carried with the support of 53 nations including Cuba, Iran, Venezuela and, of course, China. Many of the supportive nations have questionable human rights records.

The ‘yes’ votes included a mix of nations that always align with China and others, many from Africa, that were added to the list because they’re locked into infrastructure projects under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Papua New Guinea voted ‘yes’. Sadly, that has not been reported in PNG’s daily media, or even on social media.

By voting to support the crushing of free speech and freedom of assembly, among other basic rights, PNG voted against the spirit of its own constitution, adopted at independence in 1975, which guarantees those rights for its citizens, along with a free press.

To its enduring credit, PNG’s Supreme Court has vigorously protected these constitutional freedoms against legislation and against regulations seeking to erode them or even put limits on them.

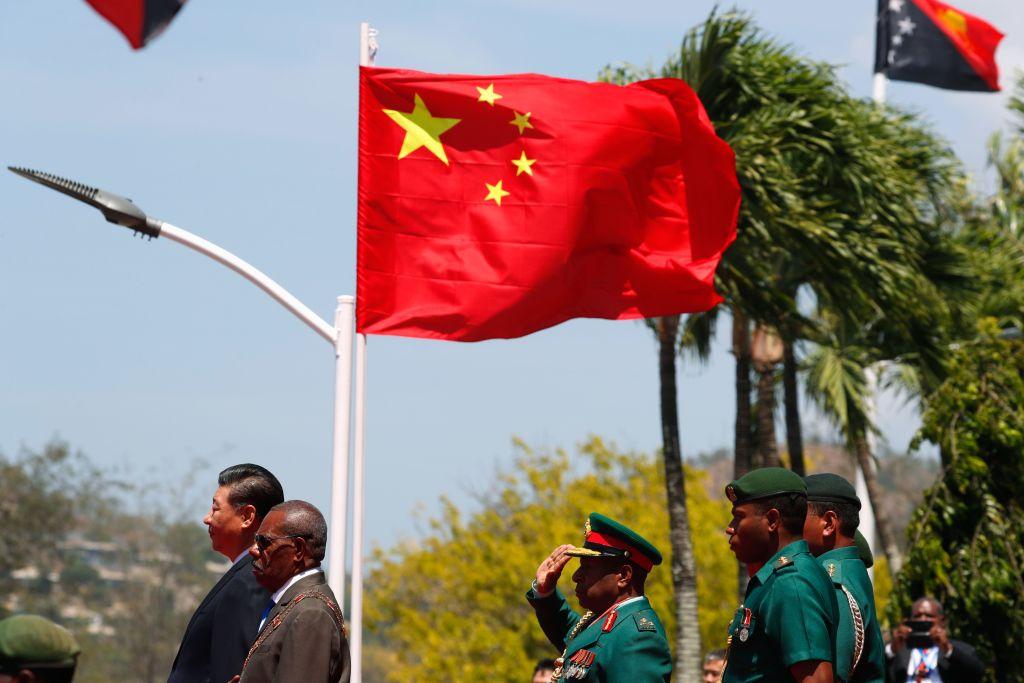

PNG’s vote in the Human Rights Council is a sad reflection of the state of foreign policy in our closest neighbour. Instead of pursuing an independent policy, also provided for in the constitution, PNG is increasingly aligning itself with the People’s Republic of China when it counts.

This has not been debated seriously in the national parliament or, I suspect, even by the National Executive Council, PNG’s cabinet.

There can be only two reasons why PNG voted as it did, and as it increasingly does in regional and international forums. Both present serious foreign policy challenges, and regional security and stability challenges, for Australia.

First, PNG acted in similar fashion to the African nations lined up behind China—the PNG government signed up to the BRI in 2018 and that program is gradually expanding across the South Pacific.

There can be no doubt that funding, principally via heavily conditional loans, under the BRI for developing nations—and jurisdictions in developed countries, such as the state of Victoria in Australia—depends on these countries and jurisdictions supporting the PRC line in bodies where it exerts considerable influence, such as the Human Rights Council and the World Health Organization.

PNG is now locked into that, though neither the parliament nor the people were told this would be the case when, with much fanfare, PNG signed up to the BRI.

The second reason is less certain, but more profoundly troubling if it is true.

PNG has yet to agree to an emergency support package led by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which is probably worth at least $3 billion. Negotiations are believed to be continuing but, frankly, PNG is running out of time.

The PNG economy is deteriorating rapidly, a problem that’s hardly helped by the continued closure of the Porgera Gold Mine which the government is seeking to effectively nationalise.

The government is running out of cash, with the fortnightly payroll for the public service and parliamentarians being delayed regularly.

The problem the government clearly has with the IMF–World Bank package is the conditions that will come with it. Past experience indicates that those conditions will include a substantial currency devaluation, asset sales, and a substantial reduction in the size of the public service.

With national elections now less than two years away, such a package is hard for the government to embrace.

The real concern is that, out of sheer desperation, the government might do what it was clearly contemplating almost a year ago and accept a substantial rescue package funded by the PRC.

Australia intervened just in time and provided a $400 million soft loan (which is unlikely ever to be repaid) that effectively replaced emergency assistance from China, and put on hold a much larger package.

In desperate times—and these are the most desperate times in PNG’s history—governments surrender good fiscal policy and even national integrity and security. We can only hope that’s not what PNG will do in the coming months.

The question which now arises is how Australia should respond to this troubling reality.

The answer must not be to give PNG more cash handouts as we did a few weeks ago when we agreed to convert $20 million from the aid program to cash.

We have to encourage PNG to accept the IMF–World Bank package, to which we will no doubt contribute, without delay.

We must also encourage PNG to address investment policy issues that are impeding the development of major resource projects, especially those in which there is Australian equity, such as the Wafi-Golpu mine project and the Papua LNG project.

As I have written before, Australia must urgently and comprehensively review its generous aid program so that it reduces waste and bureaucracy and focuses on the real needs of the people of PNG.

Hundreds of programs that are poorly implemented and managed undermine our credibility in our closest neighbour. They must be urgently refocused on helping PNG reverse the real decline in the basic living standards of its people—people who value the friendship with Australia and are rightly suspicious of the growing lock China has on key areas, now clearly including foreign policy.

The Australian government’s ‘Pacific step-up’ program alone cannot do that if it means continuing the same aid programs and simply adding more dollars to them. Our relationship with our closest neighbour is vital for our national security and the stability of our region.

It needs urgent and robust repairing and refocusing.