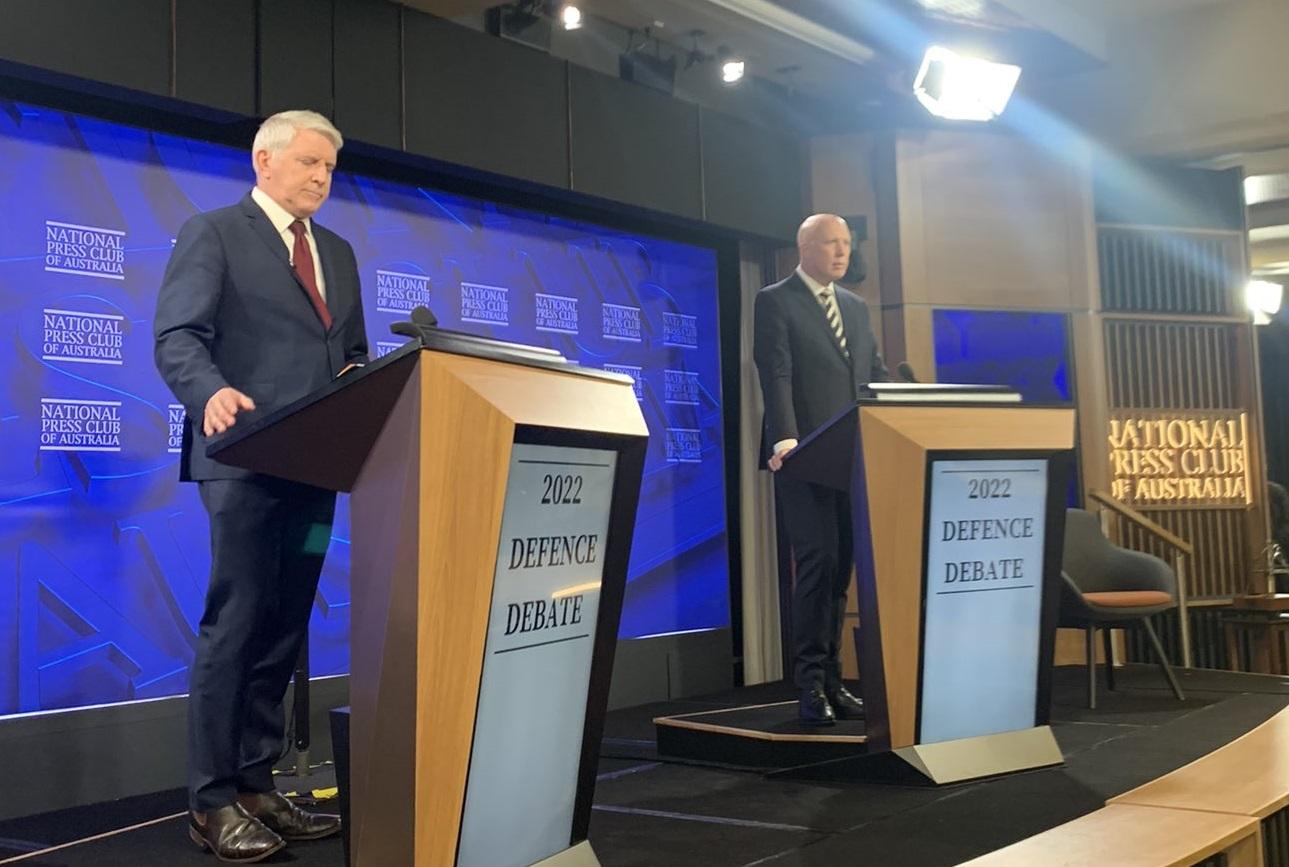

In this afternoon’s defence debate at the National Press Club, much of the Labor–Liberal consensus was as firm as ever: more money for the military, build nuclear submarines, worry about China.

Both sides concur on scary times. Then the politics kicks in hard, as it must only a fortnight from the vote.

The Liberals argue that Australians should be scared about how ‘weak’ the Labor Party is on defence spending. Stick with the government with a firm record, advises Defence Minister Peter Dutton, and don’t risk Labor.

The pushback from Labor’s shadow defence minister, Brendan O’Connor, is that it’s scary how little the government has actually delivered to deal with the times. O’Connor said that the coalition government had six defence ministers in the nine years since 2013. Under Scott Morrison as prime minister, there’d been four defence ministers in four years. The result had been ‘inadequate oversight and focus on this portfolio’.

These were the political parameters for the election debate between Dutton and O’Connor. View the contest using a series of headings.

Scary strategic settings. ‘We are facing a future that is more uncertain and a region that is less safe,’ Dutton said. What was unthinkable even a year ago, he said, is now our reality, 70 days into Russia’s ‘immoral and illegal invasion’ of Ukraine. China’s intimidation and coercion, he said, is ‘threatening the sovereignty and prosperity of every Indo-Pacific nation’. Ditto, said O’Connor.

China. The two sides agree on a different, scary China (‘alarming’, said Dutton). The politics is in Dutton’s claim that Labor would appease Beijing and that China wants Labor to win the Australian election:

We are dealing with the reality of a new China. Australians should be wide-eyed about this. I think people should be under no illusion. There’s no need to embellish the intelligence that we’re reading. There’s no need to pretend that something is happening.

The fact is that every like-minded country has drawn a similar conclusion about the direction of China. Now there’s no doubt in my mind that the Chinese Communist Party would like to see a change of government at the 21 May election. No question at all.

Responding that Dutton’s comment was untrue, O’Connor said China would get no benefit from a Labor victory: ‘We know China has changed. We know it’s now more assertive, more aggressive, more coercive.’

He criticised the Morrison government for abandoning strategic ambiguity about a potential war over Taiwan. But Labor did not blame the government for China’s shifts, O’Connor said: ‘I’ve made it unequivocally clear that it’s not the Australian government or Australia that has changed its behaviour. It is China.’

O’Connor questioned Dutton on his November comment that it was ‘inconceivable’ that Australia would fail to join the US in a Taiwan conflict. The Labor shadow minister asked the defence minister if he’d reflected that it was wrong to answer the hypothetical question.

Dutton replied: ‘Do I think we would shirk from our responsibility to be a good ally with the US? No, I don’t. And I don’t think that would be in the interests of our country.’

South Pacific and Solomon Islands. O’Connor said the government had ‘dropped the ball in the Pacific. Not being seen to treat Pacific island countries fairly or seriously. Cutting foreign aid. Mocking their concerns about climate change, by failing to comprehend the importance of soft-power diplomacy.’

He said the relationship with Solomon Islands had deteriorated and the Solomons’ security pact with China was a Canberra failure: ‘It’s happened under Scott Morrison’s watch and he has to take some responsibility.’

Dutton responded that Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare had not criticised Australia: ‘He’s not saying that the relationship is broken. He’s not saying that Australia is an unreliable partner.’

Defence spending. The consensus on 2% of GDP on defence is a talisman grasped by both sides, even as inflation asks new questions about the value that can be delivered.

Dutton said the government is building a ‘larger, stronger and better defence force’, increasing its size by 30% to get a total force of 80,000 personnel and putting $270 billion into capability this decade.

When the coalition came to office in 2013, Dutton said, Labor had cut defence spending to the lowest levels since 1938, at 1.56% of GDP. Labor had ‘delayed, cut or cancelled over 160 projects’.

O’Connor replied that in the six years to 2013, the Labor governments of Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard had spent an annual average of 1.7% to 1.8% of GDP on defence. Much had ‘dramatically changed,’ he said, since China’s Xi Jinping addressed Australia’s parliament in 2014.

Labor supported the defence acquisitions announced by the Morrison government, O’Connor said, but the government didn’t deliver what it pledged:

This government has failed to deliver the defence capabilities that this country needs. In almost a decade they have not delivered the assets they promised. [The Australian’s] Greg Sheridan recently wrote that if you could guarantee Australia’s security by announcements that have been made, we’d be the most secure nation in the world.

The spending duel—who has done, or will do, the best job—often becomes an exchange of historical analogies.

History wars and the US alliance. In campaigns, many ghosts rise up, defining the future by referring to the past.

O’Connor began his address by noting the 80th anniversary of the US and Australia joining in the battle of the Coral Sea—‘a tactical draw but a strategic victory’ in the fight for Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. The wartime Labor leader John Curtin had been responsible for the ‘strategic pivot’ to the US ‘to defend this nation effectively. Eighty years on, that important security alliance is still in place, and it has been deepened and broadened, and in large part that’s because of the bipartisanship it enjoys.’

Labor’s recent achievement in office had been to get the US Marines to Darwin, O’Connor said, while Morrison had been treasurer when the Port of Darwin was sold to China on a 99-year lease.

‘We live in times echoing the 1930s,’ Dutton said, ‘with belligerent autocrats seeking to once again use force to achieve political outcomes. If history has taught us anything, it is that when dictators are on the march, you can only preserve peace by preparing for war. You can only deter aggression from a position of strength.’

Dutton raised the ghost of Mark Latham, Labor’s leader in the 2004 election, claiming he would have broken the US alliance. The alliance was safe with the Liberal Party, Dutton said, but Labor’s ‘hard left would break the alliance tomorrow’. O’Connor’s interjected response: ‘That’s absurd.’

Nuclear submarines for Australia. The AUKUS agreement offers an entirely new dimension to defence, Dutton said: ‘The range, the stealth, the survivability of nuclear-powered submarines make them an incredibly powerful deterrent and capability for our country, underpinning the security of our nation for the next 50 years.’

The defence minister and his Labor counterpart tacitly joined hands to tiptoe around the question of whether the first of the nuclear submarines should be built overseas—in the US or Britain—to get the capability sooner.

Both promised to build subs in Oz. ‘Our commitment is to see them built here in South Australia,’ Dutton said. ‘Ideally, you build defence assets here,’ O’Connor said. Both pointed to the time it’ll take to train Australians to crew nuclear subs.

The defence minister said Australia was condensing the 18-month timeline to make a choice between US and British nuclear submarine designs.

Both professionals landed plenty of blows. But no knockouts. The defence consensus between the two parties of government skipped through the bout with hardly a bruise.