The risk of prison radicalisation has been a complex challenge to national security for decades. Whether arising from ethno-nationalist, separatist or jihadist inmates, the threat of extremist ideas and beliefs spreading inside prison walls is not a new phenomenon. What is new, however, is the recent decision by the NSW government to create a separate wing in Goulburn jail’s supermax complex to house the existing 54 inmates who have been convicted for terrorist-related offences.

This strategy has been discussed for some time; in late 2016, the UK government published a report recommending that specialist units be built to ‘allow greater separation and specialised management of the highest risk individuals’. The Netherlands has endorsed the practice of separation for over 10 years. The benefits and drawbacks of that approach are still being explored, though there’s been no actual evidence-based review concluding that it will work. It simply reinforces the trend of governments resorting to increasing securitisation, rather than focusing on reform and rehabilitation of individuals.

Proponents of separation policy argue that keeping known extremists and terrorists away from ‘ordinary’ inmates is a credible solution to the ‘growing problem’ (PDF) of Islamist extremism in jails. According to an ICSR report, prisons are ideal spaces for extremist and radical ideology to spread because they house many mentally and physically vulnerable individuals whose ‘cognitive openings’ can be easily exploited. Thus, working to reduce, and hopefully eliminate, the emergence of new extremists behind bars is a logical goal.

Critics of separation policy have proffered equally compelling arguments. Creating an isolated wing for terrorists and extremists presents two particularly complex challenges for prison authorities, governments and the wider communities.

First, segregating the inmates risks reinforcing their beliefs. That approach is generally not favoured internationally as it’s understood that dispersal may create opportunities for deradicalisation or disengagement from extremist ideas. Not all terrorists and extremists are the same, nor do they necessarily hold the same beliefs. Those who are not as far down the radicalisation path could be more receptive to rehabilitation and disengagement than more hard-line inmates. Housing all extremists and terrorists together may expose less radical individuals to the more irredeemable inmates, solidifying beliefs that might have been moderated in a less highly charged atmosphere.

Second, segregated inmates may be more likely to re-create operational command and control structures behind bars that are difficult for prison authorities to break down. For example, in France last year, 12 ‘radicalised’ inmates who were suspected of ‘“structuring” protest movements’ were removed from one prison and dispersed into others. Permanent isolation of such inmates is impossible because it contravenes certain codes of conduct under European human rights conventions (PDF).

We need to be careful about how we label offenders—particularly those who’ve been convicted of political violence or terrorism. Segregating certain prisoners based on the nature of their crime may give more clout to the individual and validate their actions on the ideological level. It could risk strengthening their message rather than weakening it. That was the case with IRA prisoners who became ‘symbols of oppression, serving the group’s wider political interests’.

Importantly, the numbers speak for themselves. There aren’t many ‘radical’ prisoners in NSW—out of 13,000 inmates in prisons across the state, there have been just four confirmed cases of radicalisation. The priority must be to give prison staff appropriate training and resources so they can deal with each case individually. More emphasis should be put on developing individual rehabilitation mechanisms to prevent further and future radicalisation.

Individuals need to be assessed for the level of risk they pose to the outside community, and whether they’re at risk of being further ‘radicalised’. That requires a different approach which balances the dual responsibilities of security and reform (PDF), without forsaking the latter for the former. For example, staff need to be trained to distinguish between genuine religious converts and those who engage with powerful prison gangs, behind a religious identity, for credence and protection. Assessing the rationale behind individual changes of behaviour may be a helpful indicator for potential disengagement.

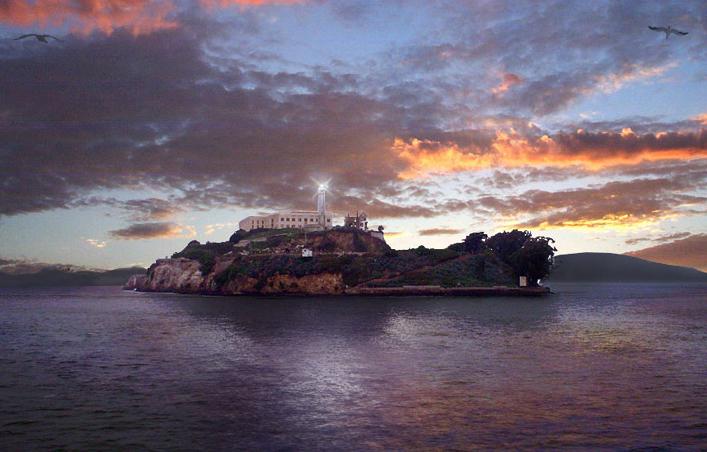

Focusing solely on security—as in the NSW approach—relies on prioritising short-term effectiveness over longer-term sustainability. Locking up people indefinitely—Alcatraz- or Guantanamo-style—is not sustainable; as legislation stands, they’ll have to be reintegrated into the community. Prisons are not single-purpose institutions. Although they aim to deliver punishment for a crime, and to prevent future crimes, they should also aim to reform individuals, allowing them to eventually become law-abiding citizens.

Prison rehabilitation programs from Saudi Arabia to Singapore emphasise social reform and training as part of their phases of treatment. Those programs don’t always work, and some individuals relapse after their release. That’s not to suggest that Australia should follow suit, but to draw attention to the range of options available for prison reform. What’s clear is that the strategy needs to change. Instead of funnelling money into extending punitive measures and heightening security, the resources could be directed towards providing inmates with the necessary tools to assist with long-lasting disengagement from their warped world view. That will be beneficial to broader security concerns in the long run.

The assumption that creating an exclusive wing for terrorist offenders will curb the spread of their ideology is inaccurate at best, and counterproductive at worst.