A subset of a pro–Chinese Communist Party network, known for disseminating disinformation on US-based social media platforms, is breaking away from its usual narratives in order to interfere in the Quad partnership of Australia, India, Japan and the United States and oppose Japanese plans to deploy missile units in southern Okinawa Prefecture.

‘Osborn Roland’ joined Twitter in August 2021 and claims to be concerned about the military deployments in Okinawa. A Facebook account named ‘Vivi Wu’—who apparently speaks German, Spanish, French, English and Chinese—says that the Japanese ‘are treated as dogs by the United States’. Korean-named ‘Hag Yoenghui’, who has an Arabic profile description, tweeted: ‘We in Australia originally supported the United States to fight against China, and the relationship with China was extremely tense … Why does our government help the United States to deal with China?’

So far, ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre researchers have uncovered 80 accounts—and counting—across Twitter, Facebook, Reddit and YouTube that since December have posted in multiple languages opposing Japan’s military activities and the Quad. The timelines of these accounts show they previously posted content consistent with the pro-CCP Spamouflage network, which typically targets topics relevant to Chinese diaspora communities and amplifies narratives that align with the CCP’s geopolitical goals.

Past campaigns have focused on smearing Chinese dissident Guo Wengui, denying human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, promoting Buddhist sects supported by the CCP’s United Front Work Department, co-opting the StopAsianHate hashtag and disseminating Covid-19 origin conspiracy theories.

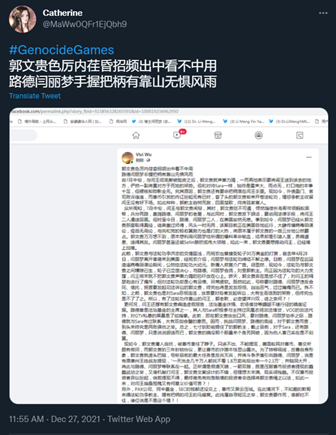

Like with previous campaigns, this network is poorly operated. Errors in hashtags, incomplete URLs to Chinese state media articles and evidence of instructions posted in a tweet are clear indications of coordination and possible automation. One Twitter account named ‘Catherine’ posted a screenshot of their working environment while sharing a Facebook post from ‘Vivi Wu’. The image revealed that the operator of this account saved bookmarks to an ‘offshore navigation and internet access’ (境外导航 –上网从) website and two Canadian Chinese news websites, ‘Anpopo Chinese News’ (安婆婆华人网) and ‘Fenghua Media’ (枫华网), and was closely monitoring Chinese virologist Yan Limeng’s multiple Twitter accounts.

Like with previous campaigns, this network is poorly operated. Errors in hashtags, incomplete URLs to Chinese state media articles and evidence of instructions posted in a tweet are clear indications of coordination and possible automation. One Twitter account named ‘Catherine’ posted a screenshot of their working environment while sharing a Facebook post from ‘Vivi Wu’. The image revealed that the operator of this account saved bookmarks to an ‘offshore navigation and internet access’ (境外导航 –上网从) website and two Canadian Chinese news websites, ‘Anpopo Chinese News’ (安婆婆华人网) and ‘Fenghua Media’ (枫华网), and was closely monitoring Chinese virologist Yan Limeng’s multiple Twitter accounts.

In August last year, Defence Minister Nobuo Kishi confirmed that Japan was emplacing anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles on Ishigaki Island to defend Japan’s contested southwestern islands and counter Chinese anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities that could prevent the US from intervening in a regional conflict. This followed a broader shift in Japanese foreign policy in 2021 which described China’s military assertiveness as a ‘strong concern’ and provoked Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to suggest Japan was being ‘misled by some countries holding biased view against China’.

In response to these announcements, the network of pro-CCP accounts leveraged local concerns about the environment and the tourism industry in Ishigaki to try to prevent the missile emplacement and suggested Japan ‘was acting as a pawn for the United States’ in an attempt to undermine the bilateral relationship. This included posting photos of atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In response to these announcements, the network of pro-CCP accounts leveraged local concerns about the environment and the tourism industry in Ishigaki to try to prevent the missile emplacement and suggested Japan ‘was acting as a pawn for the United States’ in an attempt to undermine the bilateral relationship. This included posting photos of atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Other accounts in the network posed as citizens in Australia, India, Japan and the US to criticise the Quad diplomatic partnership by spruiking their economic relationships with China. These covert efforts coincided with a Chinese state media article posted in December arguing that Japanese politicians are ‘attempting to interfere in the Taiwan Straits’ and the ‘international community should be highly vigilant about Japanese right-wing forces’ mentality of playing with fire’.

Some accounts amplified Change.org petitions created in 2019 that sought to stop the construction of missile bases on Ishigaki. By this month, the English-language petition had 312 signatures while the Japanese-language version had more than 6,000. Based on our analysis of previous CCP information operations, we expect pro-CCP accounts in this network to co-opt other similar local petitions and protests. One account has already amplified reporting of a December protest over the use of private ports in Ishigaki by the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

This emerging reiteration of the Spamouflage network has only recently started replenishing with newly created accounts and content, so the impact of the campaign has been low. Most tweets have received at most two interactions and most accounts have fewer than 10 followers. These types of networks, however, can quickly scale up to tens of thousands of accounts and persist on US-based social media platforms for years before being retweeted or amplified by an influential opinion leader or government official. It took Russia’s Internet Research Agency at least two years to prepare before it interfered in the 2016 US election.

This emerging reiteration of the Spamouflage network has only recently started replenishing with newly created accounts and content, so the impact of the campaign has been low. Most tweets have received at most two interactions and most accounts have fewer than 10 followers. These types of networks, however, can quickly scale up to tens of thousands of accounts and persist on US-based social media platforms for years before being retweeted or amplified by an influential opinion leader or government official. It took Russia’s Internet Research Agency at least two years to prepare before it interfered in the 2016 US election.

Twitter has previously attributed these networks to the Chinese government, which makes them useful for gaining insights into the CCP’s broader political and psychological warfare strategies.

Overall, the campaign indicates that the CCP is concerned about the strengthening alignment between countries in Europe, NATO, Asia and the Indo-Pacific following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Eroding alliances such as the Quad, AUKUS, ANZUS and NATO will remain the CCP’s main strategic goal.

It also demonstrates that the network is highly agile and can switch quickly from targeting Chinese diaspora and disseminating propaganda to engaging in military-related information operations and interference in foreign force posturing. Aspects of this campaign sought to shape local domestic Japanese sentiment through intimidation, which is more akin to psychological warfare than propaganda.